First Family in American Railroading

First Family in American Railroading

The railroads that stretch out of Hoboken and across the country are in large part the fruit of the brilliant minds of John Stevens and his son Robert.

John Stevens was a visionary advocate of steam-powered railroads at a time when few could even imagine how they would work. Around 1810 he turned the steamboat operations over to his capable sons and devoted himself to improving overland transportation. In 1811 he applied for a railroad charter but the state rejected it, regarding the idea as fantastic.

In 1812, shortly before the start of a war with England that would make sea transport hazardous and overland transport tremendously costly, Stevens issued a pamphlet arguing for railroads. The descriptively titled “Documents Tending to Prove the Superior Advantages of Rail-ways and Steam Carriages over Canal Navigation” was incredibly forward thinking in its advocacy of rail travel. There were no steam-powered locomotives in existence in 1812. Railroads at the time were mere wooden planks topped with iron sheets, on which carriages would be pulled by horses. They were short and their applications were limited.

Stevens’ pamphlet was impressively accurate in its predictions and civic-minded in its arguments. The visionary included letters in which he argued that building a railroad with steam locomotives would be a better use of resources than building the Erie Canal. He hoped the federal government would take note and establish railroads in all directions to “embrace and unite every section of this extensive empire. It might then, indeed, be truly said, that these States would constitute one family, intimately connected, and held together in indissoluble bonds of union.” He considered commercial, financial, military, political ramifications, calculated costs, and addressed common objections.

Stevens’ pamphlet did not gain much support for railroads, but he pressed on. In 1815 he obtained the first railroad charter in America. The route, from the Delaware River near Trenton, to the Raritan River near New Brunswick, where passengers could then board ferry boats, was not built for years, as Stevens had trouble attracting investors.

Colonel Stevens knew he had to do something to create more enthusiasm for railroads. In 1825 he built a circular railroad track on his land in Hoboken. He also constructed the first locomotive built in America, which was 16 feet long and 4ft, 2.5 inches wide. Power went to a gear that linked into a cog midway between the rails. The circular track was about 200 feet in diameter. One side was made 30 feet higher than the other to disprove a common belief that steam railways would need to be level.

In May of 1826, the experiment was ready. To the numerous observers visiting his land, Stevens demonstrated the locomotive. Its first trials were taken at 6 mph, but it later was able to achieve 12 mph carrying 6 passengers. The circular railroad generated considerable attention and most observers became enthusiastic about railroads as a new means of transportation.

While John Stevens more than anyone brought the railroad into American discussion, it was his son Robert who determined the shape that railroads would take.

While John Stevens more than anyone brought the railroad into American discussion, it was his son Robert who determined the shape that railroads would take.

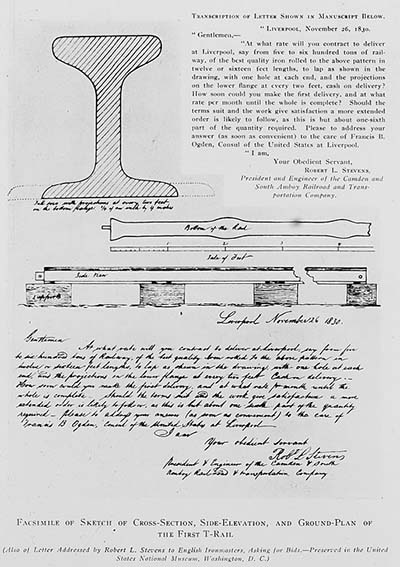

In 1830, Robert Stevens was president of the new Camden and Amboy Railroad. At that time, the few railroads in existence used wooden rails with iron straps along the top surface that contacted the wheel. Some railroads in England used a metal T-shaped rail that was expensive and difficult to produce.

Robert Stevens advocated all-iron rails and travelled to England to procure them. On the trip, he designed a new T-shaped rail that did not require complicated iron working to seat. Robert’s design, which featured a continuous base running the length of each rail, would make it more cost-effective to lay long lengths of rail, especially in the American countryside where iron workers were scarce. He also created the hook-headed spike that is essentially the same as the railroad spike used today and designed the nuts and bolts to hold everything together. Rails today are the same shape as Robert designed, with only slight changes in proportionate dimensions. In another innovation, it was under Robert’s direction that the Camden and Amboy railroad began using wooden ties with crushed stone ballast between them for the rail bed, which was found to work even better than the stone rail bed previously used.

Just as his father had opened America’s eyes to the possibility of steam locomotives, Robert Stevens brought America the first locomotive to be used commercially in the country. While in England he became friendly with the Stephenson family, important builders of steam locomotives. He watched demonstrations of their work, and ordered a similar engine to be shipped to America. The new locomotive, the John Bull, was assembled by the C&A master mechanic. A tender, water tank and hose was added and the John Bull was ready to go.

Just as his father had opened America’s eyes to the possibility of steam locomotives, Robert Stevens brought America the first locomotive to be used commercially in the country. While in England he became friendly with the Stephenson family, important builders of steam locomotives. He watched demonstrations of their work, and ordered a similar engine to be shipped to America. The new locomotive, the John Bull, was assembled by the C&A master mechanic. A tender, water tank and hose was added and the John Bull was ready to go.

On November 12, 1831, the first public trial of the John Bull was held on a thousand feet of track laid out in Bordentown, New Jersey. Members of the state legislature were the first to ride the train. Following the successful tests, locomotive shops were set up in Hoboken, where three engines were produced over the next two years. One of the improvements devised by Robert was a set of pilot wheels attached to the front of the locomotive to help it safely travel sharp curves. This device would later become known as the “cow catcher.”

The Camden and Amboy Railroad had required serious lobbying efforts to obtain an effective charter. From 1828 to 1829 the Stevens brothers successfully petitioned the legislature to change the family’s old charter. The charter now called for a railway from a point opposite Philadelphia to point on the Raritan Bay, which would allow for more reliable and safer steamboat connections. Beginning with Robert Stevens as president, Edwin Stevens as treasurer, and Robert Stockton as a leading political operative, the C&A would become a significant force in New Jersey politics as it pioneered rail travel.

The Camden and Amboy management forged close links to the state government. While the Stevens family held the main financial interests in the C&A, Robert Stockton built a political machine that allowed the company to exercise a powerful influence in the state government on all matters of transport across the state. The railroad gave the state shares of stock, paid duties on passengers and freight, and guaranteed a minimal annual contribution of $30,000 to the state treasury. In return they were legally guaranteed a monopoly on rail transit across the state between New York and Philadelphia. The deal would be forfeit if competition was allowed.

In 1836 the C&A management offered to sell the railroad at cost to the state. The rejection of the deal may have made the railroad’s management seek more political influence. Legislators were given free riding passes and newspapers were bought or created. Economic development in some areas of the state was hindered as the C&A prevented the construction of railroads that they believed would compete with their Philadelphia-New York duties. With monopoly came higher transport prices than existed in states that allowed competing lines.

Yet the Camden and Amboy management held that their operation benefitted New Jersey. While there were some disputes over payment, the railroad did contribute a significant amount of money to the state treasury each year, meaning that state taxes were very low. Stockton argued that important local railroads had not been impeded, but only speculative schemes for railroads across the state that would primarily benefit investors from outside the state.

After years of political battles it became clear that the time of monopoly would end. In 1854 the Legislature declared that the Camden and Amboy’s monopoly privileges would end in 1869.

While the Camden and Amboy Railroad came to exercise a level of political power that many recognized as inappropriate, it launched a new era in rapid transit and interstate travel. The railroad’s innovations and hard-won success establish the Stevens family as pioneers in American railroading. The vision, ingenuity, and entrepreneurship of the Stevens family made them central figures in the creation of a modern, effective transportation network for a growing country.

Sources

History, Stevens Institute of Technology. www.stevens.edu

Jim Hans, 100 Hoboken Firsts. 16.

John Stevens, “Documents Tending to prove the Superior Advantages of Rail-ways and Steam Carriages Over Canal Navigation.” Archive.org.

J. Elfreth Watkins, “John Stevens and His Sons,” 5, 7. Stevens Family Collection.

Mary Stevens Baird Recollections, Stevens Family Collection. VI.

“New York World’s Fair Bulletin,” Hoboken Chamber of Commerce. 2. Stevens Family Collection.

Wheaton J. Lane, From Indian Trail to Iron Horse. Inventions, 281-283, 286-288; John Bull, 287-288; C&A Politics, 284-286, 289-303, 307, 318, 325-337, 343, 357-359.