Category Archives: Stevens Family

Steamboat Innovation

Steamboat Innovation

According to legend, Colonel Stevens was riding near the Delaware River in 1787 when he happened to see John Fitch’s experimental steamboat travelling up the river. He was so intrigued he followed the boat to its dock and thoroughly investigated it. Whether this chance meeting happened, or if it was regular correspondence with other learned men that sparked Stevens’ interest in steam power, by the late 1780s he was driven to work on the steam engine’s applications for transportation.

John Stevens conducted his own experiments in steam power. He corresponded with John Fitch and James Rumsey, who had been experimenting with steam power for boats. In 1789 he applied unsuccessfully to the New York Legislature for exclusive rights to operate steamboats in the state. In 1790 he persuaded Congress to pass the first American patent law and on August 26, 1791, he received one of first patents for an application of steam power.

Stevens’ experimental boats pioneered steam navigation in America and attracted modest but significant attention. As early as 1798, he demonstrated the Polacca, a steamboat that carried passengers from Belleville, New Jersey, to New York City. Speed estimates ranged between 3 and 5.5 mph. The experimental craft was driven by a wheel in the stern. Though the Polacca demonstrated the possibility of steam propulsion, its piping and seams were broken open from the vibration of the engine and it was not yet a practical means of transportation.

In 1804, Robert, then 17, and his brother John, assisted their father in constructing the first boat propelled by twin screw propellers. The Little Juliana, a 32 foot boat with a boiler designed by Stevens, successfully navigated the Hudson River and amazed onlookers by travelling without a visible means of propulsion. However, screw propulsion would require high pressure steam to be efficient, and engineering methods of the time were not advanced enough to successfully make high pressure boilers.

In 1804, Robert, then 17, and his brother John, assisted their father in constructing the first boat propelled by twin screw propellers. The Little Juliana, a 32 foot boat with a boiler designed by Stevens, successfully navigated the Hudson River and amazed onlookers by travelling without a visible means of propulsion. However, screw propulsion would require high pressure steam to be efficient, and engineering methods of the time were not advanced enough to successfully make high pressure boilers.

In 1805 Colonel John received a British patent for a new kind of boiler for steam engines. Unlike earlier models that contained one large tube for heating water, John’s design heated water in multiple smaller tubes. It was more expensive to produce than earlier models but was significantly more efficient.

The Stevenses built two more experimental steamboats in 1806 and 1807. Their next steamboat, the Phoenix, would enter history as the first steam-powered vessel to complete an ocean voyage, and the first commercially successful steamboat built entirely in America. It would also launch a dispute with Robert Fulton and the Livingston family.

Robert R. Livingston had worked with John Stevens on his early steamboat experiments, but left for France on government business in 1801. There he met Robert Fulton, who was also interested in steamboats. Livingston gave financial and technical aid to Fulton, but more importantly he had legal knowledge and influence in New York politics. In 1798 Livingston had obtained a monopoly of the right to navigate steamboats in New York after his own experiments, a monopoly that he would soon exercise in partnership with Fulton.

In the summer of 1807, Fulton’s Clermont steamed from New York City to Albany in 32 hours. The trip established Fulton’s place in history as the designer of the first successful steamboat. News of his voyage spread quickly.

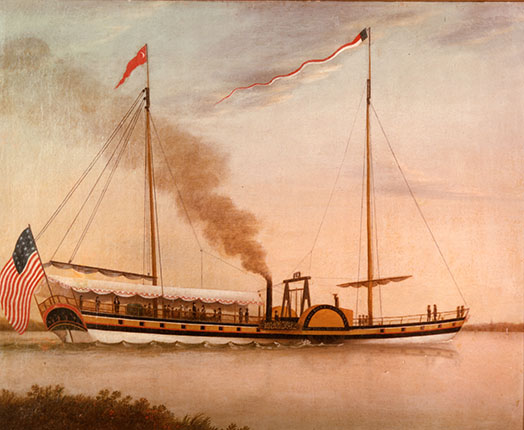

Meanwhile the Stevens family continued their engineering work, and the Phoenix was launched in the spring of 1808. Propelled by paddlewheels on its sides, the Phoenix averaged over five miles per hour. Its 100 foot hull was designed by Robert Stevens, then twenty years old. Like many early steamships, the Phoenix included masts for sails to be used when the wind was favorable. Unlike the Clermont, for which Fulton and Livingston had acquired a British steam engine, the Phoenix was designed and built entirely in America, the first successful steamship to be entirely American in origin.

In the first decade of the 1800s, large-scale transportation infrastructure, including major roads, was typically built by private partnerships who would then operate under grants of monopoly from state governments. Steamboat service to New York, despite the Stevens’ protests, would operate on the same principle. While Livingston was inclined to compromise with his relative and former associate, Fulton was determined to make the most out of the grant of monopoly. Livingston offered Stevens a partnership in the monopoly, which Stevens rejected. The two men engaged in a lengthy correspondence over the constitutionality of the monopoly grant.

Stevens tried to ignore or outmaneuver the monopoly the best he could. Realizing that the Phoenix would be seized if he tried to operate it on the Hudson, he instead had the boat travel a route between New York and New Brunswick, New Jersey. Fulton and Livingston were determined to crush this competition and set one of their new steamboats, the Raritan, to run the same route as the Phoenix. The Raritan at first operated at a loss at first but later returned a modest income. With less money to lose on a rate war, John Stevens decided to withdraw his boat from servicing New York.

On June 10, 1809, John Stevens sent the Phoenix to Philadelphia under the charge of Robert, then 21 years old. At a time when it was thought steamboats were only safe in calm waters, Robert Stevens took the Phoenix out on the Atlantic Ocean. A schooner accompanied the Phoenix when the winds were favorable, but there were days when the steamer traveled alone. Robert braved rough seas, high winds, and storms on the voyage, occasionally waiting out especially treacherous weather at port. The Phoenix arrived at Philadelphia thirteen days after the journey began. The steamship would make successful business on the Delaware River, even partnering with Fulton and stagecoach companies in 1810 to for travel packages between New York and Philadelphia.

On September 11, 1811 a pier lease from the City of New York allowed the Stevens family to launch a steam-ferry service from Hoboken to Manhattan, but this was shut down by pressure from Livingston in 1813.

The Fulton-Livingston monopoly finally ended when it was declared unconstitutional in the landmark 1824 Supreme Court decision Gibbons v. Ogden. Aaron Ogden was a New Jersey politician and ferry operator. He was able to put enough political pressure on the Livingston-Fulton monopoly that they decided to sell him a license to operate in New York for a reasonable price. Ogden was a former business partner of Gibbons who competed bitterly after their less-than-amicable split. After John Marshall’s decision, states could no longer grant monopolies to steamship companies and the ports became free for competition.

Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, the Stevens family made numerous contributions to steamship design. Improvements included advances in boilers, hulls, and pressure valves. In 1822 Robert Stevens designed the ferry slip for the Hoboken Steamboat Ferry Company. Long piles were driven into the river bed and hardwood fenders were attached to them. This design made it simpler for ferries to dock in strong tides, and was widely adopted. In 1823 the family launched the first double-ended ferry boat.

Robert would build numerous steam ferries, increasing the speed of each successive craft from 8 miles per hour in 1815 to 15 mph in 1832. Robert’s New Philadelphia, with an innovative bow that cut through water efficiently, was able to complete the trip from Albany to New York City between dawn and dusk. Edwin Augustus Stevens patented the air-tight fire room in 1842. He also developed the first double-ended propeller-driven ferryboat, the Bergen, which made paddlewheel boats obsolete.

Sources

Archibald Douglas Turnbull, John Stevens, an American Record. 100-108, 185, 208, 261-280. Archive.org.

Charles King, Preface to Stevens, “Documents Tending to prove the Superior Advantages of Rail-ways and Steam Carriages Over Canal Navigation.” iv, v. Archive.org.

George Iles, Leading American Inventors. 11-13, 16. Archive.org.

J. Elfreth Watkins, “John Stevens and His Sons.” 8. Stevens Family Collection.

Jim Hans, 100 Hoboken Firsts. 4-6, 11, 15, 56.

“New York World’s Fair Bulletin,” Hoboken Chamber of Commerce. 1-4. Stevens Family Collection.

Wheaton J. Lane, From Indian Trail to Iron Horse. Steamboats, 175-184; Gibbons v. Ogden, 184-194.

Building Hoboken

Building Hoboken

While living in Manhattan with his wife, Colonel John Stevens became interested in building an estate. In 1783 he explored some land across the river. William Bayard’s farm had stood there, but it was confiscated by the colonial government of New Jersey because Bayard sided with the British Crown. On May 1, 1784 Stevens bought Bayard’s old farm from the State of New Jersey for 18,340 Pounds sterling, or about $90,000. He settled on the name Hoboken, a closer approximation to the Lenape word for the area than Hoebuck, as Bayard’s farm had been known.

In the early days John farmed and cleared trees at Hoboken, but he had other improvements in mind. He built a house on Castle Point, cleared land for development, laid out a partial street grid and had attractive landscaping done on what would become gardens and pleasure grounds. In 1794, Stevens successfully lobbied the New Jersey State Legislature to authorize a road to be laid out to Hoboken, which would compete with a chartered toll road from Newark to Paulus Hook in Jersey City.

Stevens soon brought more people to Hoboken. He began to sell lots in 1804. Until 1814 the family lived at Hoboken only in the summer, spending much of the year at the family home in Manhattan. John found the river crossing to be unsatisfactory and soon bought out a ferry company, which further added to his land holdings. The Stevens ferry and lands, including the Elysian Fields and River Walk Promenade, brought thousands of visitors to Hoboken from the 1820s to the 1850s. In first half of the nineteenth century, the Elysian Fields, north of Castle Point, was one of the most frequented pleasure grounds in the country, and could host as many as 20,000 visitors in a day.

Stevens soon brought more people to Hoboken. He began to sell lots in 1804. Until 1814 the family lived at Hoboken only in the summer, spending much of the year at the family home in Manhattan. John found the river crossing to be unsatisfactory and soon bought out a ferry company, which further added to his land holdings. The Stevens ferry and lands, including the Elysian Fields and River Walk Promenade, brought thousands of visitors to Hoboken from the 1820s to the 1850s. In first half of the nineteenth century, the Elysian Fields, north of Castle Point, was one of the most frequented pleasure grounds in the country, and could host as many as 20,000 visitors in a day.

The family sold more land in the 1830s. On February 21, 1838, the Hoboken Land and Improvement Company was incorporated. The Stevens brothers John Cox, Robert, James, and Edwin were among the six partners. The HLI Co was empowered to improve lands they owned (primarily north of Fourth Street) by dividing it into lots, grading and leveling land, constructing buildings, installing infrastructure, and renting or selling land.

Sources

Archibald Douglas Turnbull, John Stevens, an American Record. 80-88, 96, 180

Christina A Ziegler-McPherson, Immigrants in Hoboken. 27-29.

History, Stevens Institute of Technology. www.stevens.edu/

Jim Hans, 100 Hoboken Firsts. 112-115.

Wheaton J. Lane, From Indian Trail to Iron Horse. 124.

The Family

The grandfather of Hoboken’s founder, also named John Stevens, emigrated from England to New York City in 1699 at the age of seventeen. He served a seven year indenture as a clerk to a crown official in New York, then pursued interests in land and mining. He came to the Jerseys after hearing about copper mining in Rocky Hill, near Princeton. He soon found the business of land to be more profitable (though he would eventually acquire the Rocky Hill mines). While living in the Princeton area he met Ann Campbell, whose father owned land as a shareholder and proxy for New Jersey’s Proprietors. John and Ann married in 1714, and John Stevens now joined in Ann’s father’s land business. They left many scattered tracts of land in New Jersey to their children when John died in 1737.

The father of Hoboken’s founder, the Honorable John Stevens (1716 – 1792) was a prominent merchant. He served on the New Jersey Royal Governor’s council until he resigned to support the cause of Independence. He was also a slaveholder, at least for part of his life. His wife, Mary Alexander, was a daughter of the surveyor-general of New York and New Jersey. He had two children, John in 1749, and Mary in 1752. The Honorable John Stevens would serve in the New Jersey legislature after Independence as well.

⚡ Stevens Family: Fast Facts

- The Founder: Colonel John Stevens (1749–1838) founded Hoboken and was a leading advocate for the first U.S. patent laws.

- Transportation Firsts:

- Designed the first American-built steam locomotive.

- Operated the Phoenix, the first steamboat to successfully navigate the open ocean.

- The “T-Rail”: Robert L. Stevens invented the T-rail, the inverted “T” shape for tracks that became the global standard for railroads.

- The America’s Cup: John Cox Stevens founded the New York Yacht Club and led the syndicate that won the very first America’s Cup in 1851.

- Educational Legacy: Edwin A. Stevens bequeathed the land and funds to establish the Stevens Institute of Technology, the first U.S. college dedicated to mechanical engineering.

- Philanthropy: Martha Bayard Stevens was a prolific philanthropist, funding the construction of the Church of the Holy Innocents and numerous civic projects in Hoboken.

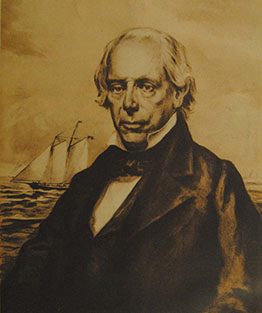

John Stevens (1749-1838), often referred to as Colonel John Stevens, was Hoboken’s founder, a patriot, attorney, and civic-minded inventor. He was a pioneer, even a visionary, in steam powered transportation on sea and land. Charles King, president of Columbia University, wrote of him in 1852: “Born to affluence, his whole life was devoted to experiments, at his own cost, for the common good… Time has vindicated his claim to the character of a far-seeing, accurate, and skillful, practical experimentalist and inventor… The thinker was ahead of his age.”

John was born in New York City in 1749, but spent most of his childhood at the family home in Amboy. In 1760, the family established a winter home in Manhattan. John graduated King’s College (now Columbia) in 1768, then studied law and became an attorney in New York in 1771.

Young John and his sister forged close relationships with the powerful Livingston family. In 1771 Mary Stevens and Robert Livingston Jr. were married. The Livingstons had significant influence in New York politics in the colonial and early republican eras. Their influence would not benefit the Stevens family when John Stevens and Robert Livingston were on opposite sides of a steamboat navigation dispute in the 1800s.

Like his father, young John Stevens joined the Patriot cause and offered his services. On July 15, 1776, he was appointed Treasurer of New Jersey. Successfully carrying out his duties in war-torn New Jersey required him to navigate the state on horseback evading British and Tory troops as he raised funds and paid bills for the state. His service earned him the rank of colonel.

Rachel Cox, a beautiful daughter of Colonel John Cox, caught John’s fancy and the two of them married in October 1782. After hostilities with Britain ceased, they moved to the Stevens home in Manhattan and planned to acquire land and raise a family. John looked across the river to the future.

Colonel John Stevens and his wife Rachel would have 13 children. Their most well-known sons are John Cox Stevens (1785-1857), Robert Livingston Stevens (1787-1856), and Edwin Augustus Stevens (1795-1868).

| John Cox Stevens | Robert Livingston Stevens | Edwin Augustus Stevens | |

| Primary Focus | Maritime & Sport | Engineering & Rail | Business & Education |

| Key Invention | Organized Yachting | The T-Rail (Standard Track) | The “Stevens Battery” (Ironclad) |

| Famous First | Won the first America’s Cup | Built the first steam locomotive in the U.S. | Founded America’s 1st mechanical engineering college |

| Organization | New York Yacht Club | Camden & Amboy Railroad | Stevens Institute of Technology |

| Defining Trait | The Visionary Diplomat | The Inventive Genius | The Strategic Philanthropist |

John Cox Stevens represented the family in business when needed and enjoyed sailing as often as he could. As a founder of the New York Yacht Club, he sailed the America to victory in the race that would become the America’s Cup.

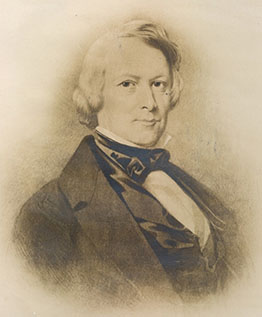

Robert’s creative imagination was noticed at an early age and as a youth he was given tools and mathematical training. Robert made an incredible number of advances in the construction of railroads and ships. He had attended Columbia like his father, but left before graduating to learn about mechanical operations in Hoboken machine shops.

Edwin had a mind for engineering and business, and he often worked with his brother Robert on joint ventures. Edwin firmly anchored the Stevens legacy in Hoboken by founding the Stevens Institute, America’s first college devoted to mechanical engineering.

There were proud civic leaders among the women in the Stevens family.

Martha Bayard Stevens, wife of Edwin Augustus, was known for her philanthropic contributions to Hoboken.

Caroline Bayard Stevens was so well regarded for her civic work that her death was mourned at the White House.

Millicent Fenwick, a great-granddaughter of Edwin, was a respected member of the United States Congress.

In 1897, Abram S. Hewitt fondly recalled the Stevens family in an address at the Stevens Institute. Hewitt had been a mayor of New York City, a member of Congress, and a leader in the ironworks business. Yet when he first visited the elderly John Stevens at Castle Point, he was a curious young boy, the son of a mechanic who had developed a friendly relation with John while working on his steam engines. Hewitt was impressed by the genuine enthusiasm and friendliness shown by the man in his eighties who was still possessed of an active and alert mind.

“I was welcomed to Castle Point in my early youth just as I would be today by the honored mistress of that mansion. They did not believe that the acquisition of wealth was sufficient for the development of human nature… The sense for beauty was manifest in all that they did.”

Sources

Archibald Douglas Turnbull. John Stevens, an American Record. Archive.org.

Charles King, Preface to Stevens, “Documents Tending to prove the Superior Advantages of Rail-ways and Steam Carriages Over Canal Navigation.” iii-vi. Archive.org.

George Iles. Leading American Inventors. Family History, 5-6; Hewitt praising the Stevens family, 35, 37-38. Archive.org.

Leading Innovation: A Brief History of Stevens, Stevens Institute of Technology. www.stevens.edu

J. Elfreth Watkins, “John Stevens and His Sons,” 3,6. Stevens Family Collection.

Mary Stevens Baird Recollections, Stevens Family Collection. V, 3.