Collections Item Detail

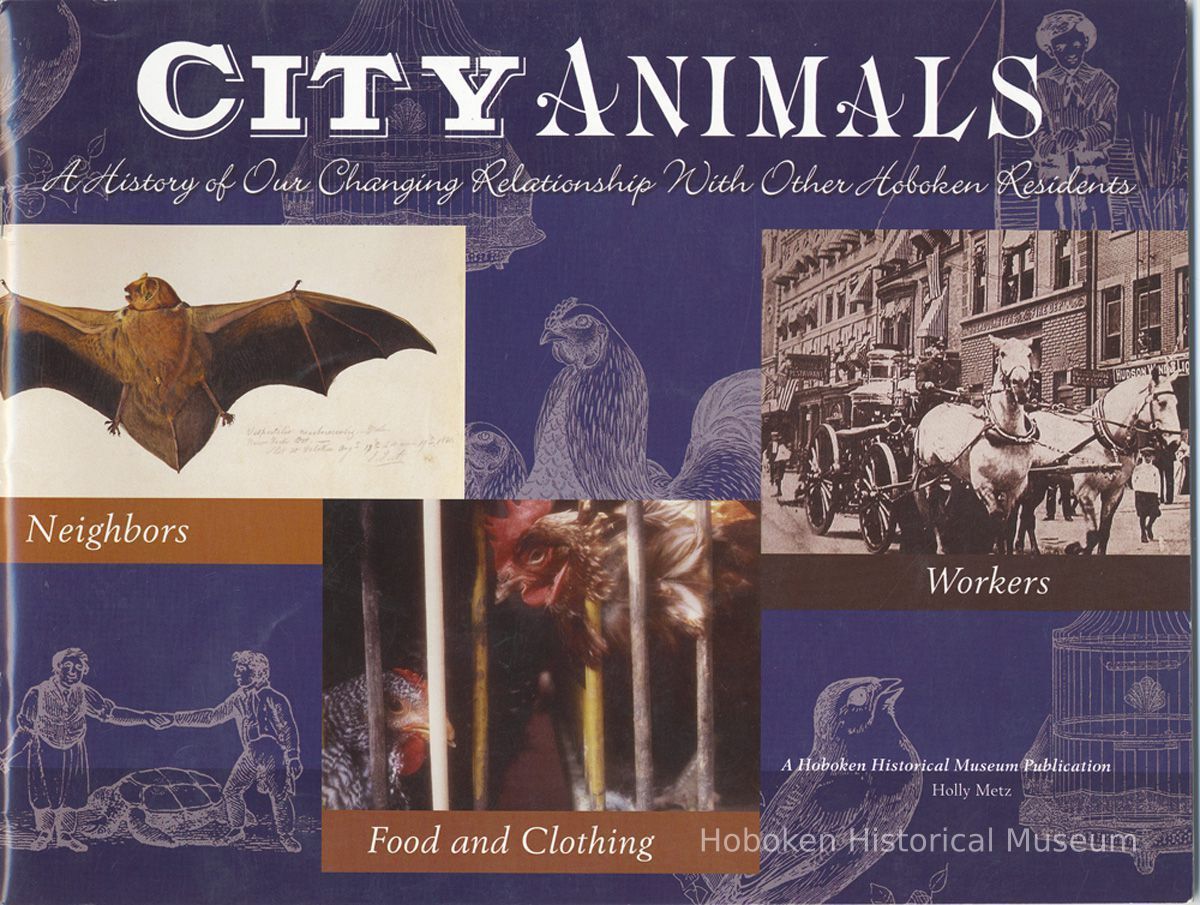

City Animals: A History of Our Changing Relationship with Other Hoboken Residents.

2005.001.0005

2005.001

Staff / Produced by

Produced by Staff

Museum Collection.

Metz, Holly

First edition.

Hoboken Historical Museum

Hoboken

2004 - 2004

Date: 2004-2004 Copy No.: 1

Good

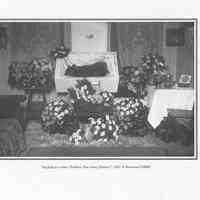

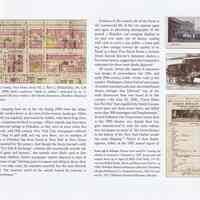

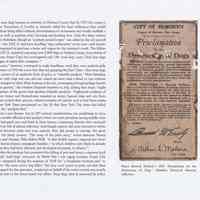

Notes: page 21 [caption for map upper left] Map of Hudson County, New Jersey, detail Vol. 2, Plate 1, (Philadelphia, PA: GM Hopkins, Co., 1909) shows numerous "sheds or stables"-indicated by an 'x' through the squared-off area-within a few blocks downtown. Hoboken Historical Museum collection. ---- Plat books mapping land use in the city during 1909 show the ubiqu- itiousness of the worker-horse in the turn-of-the-century landscape. Hobo- ken's urban grid was regularly punctuated by stables, with block-long structures built for companies involved in cartage. Other animals may have been used for commercial cartage in Hoboken, as they were in some cities, but evidence is scant: mid-19th century New York City newspapers referred to the use of dogs to pull milk and rag carts there, yet no mention of such practices in Hoboken has been found in New York or New Jersey newspapers consulted for this project. And though the Jersey Journal's early 20th-century "For Sale & Exchange" columns did occasionally include ads for "a team of goats and harness," the animals were likely used in that capacity to amuse children. Earlier newspaper reports objected to boys of "ten to twelve years of age" hitching goats to wagons and riding in them; their activities were not only cruel, the reporters asserted, but the carts blocked sidewalks and "the unsavory smell of the animal heated by exercise is anything but sweetness."6 Evidence of the central role of the horse in the commercial life of the city appears again and again in advertising photographs of the period: a Hoboken coal company displays in its yard row upon row of horses, waiting with carts to serve a vast public; a horse pulling a fine carriage conveys the quality to be found at a fancy First Street florist; a Jackson Street funeral director's stationery depicts a four-horse hearse, suggesting a most impressive statement for those most dearly departed. Of course, horses also appear in documentary images of extraordinary late 19th- and early 20th-century public events, such as the massive Washington Street funeral procession of somber mourners and crepe-decorated horse- drawn carriages that followed "one of the most destructive fires ever heard of in this country"-the June 30, 1900, "Great Hoboken Pier Fire" that engulfed the North German Lloyd piers and three ocean liners, and killed more than 300 passengers and longshoremen.7 Several Hoboken Fire Department horses died in the 1900 disaster, too, though their loss goes unmentioned in even the most exhaustive newspaper accounts of "the worst disaster in the history of the New York Harbor involving ocean shipping."8 Notice of their deaths appears, rather, in the 1901 annual report of ---- [caption for three illustrations right] From top to bottom: Horses were used for "turning the wheels of commerce." Postcard ca. 1907, horses and coal wagons lined up at Jagels & Bellis Coal Yards, 14th St., courtesy Robert Foster. Horse and florist cart, First St., ca. 1900, Hoboken Historical Museum collection; Stationery, Charles Hoffman & Co. Funeral Directors, 109-115 Jackson St., 1911, Hoboken Historical Museum collection. ==== page 22 ---- [caption photo top left] Funeral procession on Washington Street for crewmembers and longshoremen who died in the 1900 Hohoken Pier Fire. Courtesy of the Hoboken Public Library. ---- the Hoboken Fire Department, which detailed the previous year's occupational service. Twenty-one fire horses-haulers of engines, hose wagons, hook and ladder trucks and the Chief's wagon-accompanied fifty-nine firefighters to subdue the infamous 1900 blaze. The Report of the Chief Engineer of the Hoboken Fire Department describes a fire so ferocious it took eight days to be entirely extinguished. In the early stages of the Great Fire, the Chief notes, the men of Engine Co. 5, while positioned on Fourth Street between Hudson and the riverfront, were faced with a sudden wall of flames that "compel [ed] the men to flee for their lives, leaving their horses, hose wagon, and seven hundred feet of hose, all of which were totally destroyed." Veterinary Science: For Man and Beast The development of veterinary medicine was propelled by the considerable investment required in purchasing and maintaining a horse, according to Ray Thompson, a historian of Garden State veterinary science.9 At least two Hoboken veterinarians were pioneers in professionalizing this vocation, which had been previously unregulated, unlicensed and prone to quackery. Dr. David Dixon, an 1881 graduate of the private American Veterinary College, had a veterinary hospital at 66 Washington Street and was elected co-vice president at the first meeting of the New Jersey Veterinary Medical Association (NJVMA) in 1884. Dr. Richard R. Letts, an 1889 graduate of the same veterinary institution, was elected NJVMA president in 1891, after he had moved from Jersey City (where he inspected cattle in the Central Stockyards) to Hoboken (where he became veterinary surgeon for the volunteer fire department.)10 Prior to this new wave of formally educated veterinarians, early 19th century veterinary medicine was mostly based on stock remedies practiced by farriers, who primarily shoed horses; hostlers or mule-keepers; ex-jockeys and empirics who relied on experience alone in their ministering to commercially valuable animals. Knowledge might be obtained by serving an apprenticeship with an established "self-proclaimed healer," notes Thompson. Published texts often promoted bizarre and cruel cures for horses and sometimes cattle, swine or sheep. The 1827 Collection of New Receipts and Approved Cures for Men and Beast by Daniel Ballmer of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, for example, offered horse-owners the following "cure for the wind colick": Knock down a black chicken with the butt end of a whip and tear it to pieces as quickly as you can, but if you can't tear it, cut it open and take out all the entraib, then cram it down the horse's throat with your whip. This will prove a cure for the wind colick so that the horse will never get it again. Some American vets learned their trade by reading "articles in almanacs and weekly agricultural journals or by attending lectures on the care of domestic animals given to members of agricultural societies or to medical students," writes Thompson, though he argues that many practitioners were probably "not educated well enough to read them." (Indeed, the earliest private veterinary schools of the 1850s were flexible in their requirement that applicants have an elementary or grade school diploma.) Throughout most of the 1800s, quacks offered bogus remedies for a fee; some animal caretakers of the period actually followed prescriptives such as "feeding a cow a stolen dishrag will cure indigestion" and "feeding a hornet's nest to a horse will cure distemper." To distinguish themselves from such charlatans, the members of the NJVMA adopted a Code of Ethics in 1885, prohibiting "the promising of radical cures" and the "advertisement of secret remedies," disrespectful pronouncements about other veterinarians, ==== page 23 [caption for illustration left] Below: Title page, Dr. Chase's Recipes; or, Information For Everybody, the thirty-ninth edition, published in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1866, of "An Invaluable Collection of About Eight Hundred Practical Recipes" for curing diseases, mixing paint, shoeing horses, etc. Hoboken Historical Museum collection. ---- [caption for illustration top right] "Scenes at the American Veterinary College Clinic," around 1880, from Harper's Weekly. Hoboken veterinarians Dixon and Letts attended this college; it offered free clinics two afternoons a week, and included care for dogs as well as horses. ---- and "double dealing" by "giving of opinions regarding the purchase and sale of horses." By the late 1880s, when the NJVMA was founded, the state of New Jersey still had only a few university or college-educated veterinarians. Some learned the veterinary art from newly arrived immigrant veterinarians, who received formal training in Europe (there were a few such practitioners in Hoboken by the end of 19th century, as the list on page 24 indicates.) The twenty New Jersey practitioners who met in a Newark veterinarian's office to organize this veterinary association were both graduates and non-graduates of veterinary colleges. At the urging of the NJVMA, the State Legislature approved an act in 1889 that called upon veterinary college graduates and non-graduates in practice five years or more to register, for the fee of $1, with the county clerk in their county of residence. If unqualified for registration but practicing, one would face a fine of $100 or a jail term of up to one year, ==== page 24 or both. About 350 veterinarians registered statewide, though records do not indicate how many actually practiced in the state. It was a rather high number for the period, however, as there were only several thousand veterinarians in the entire United States by the late 19th century. In the 1900 Veterinary Medical Register of the State of New Jersey, in addition to Dr. David Dixon, the following Hoboken practitioners are listed: Philander G. White, 45 Washington Street, "Existing Practitioner," Date of Registry: September 4, 1889 Ferdinand Huppe, 87 Garden Street, College: Veterinary School of Cleve, Prussia; Date of Diploma: March 15, 1880; Date of Registry: June 24, 1890 Charles Patrzek, 233 Park Avenue, College: The Royal Board of Examiners of Berlin, certified by the Department of Agriculture, Berlin; Date of Registry: December 11,1893 Edward K. Stretch, 728 Park Avenue, College: New York College of Veterinary Surgeons; Date of Diploma: April 1, 1897; Date of Registry: April 14, 1897 During this period, Thompson notes, New Jersey veterinarians also began to play an active role in protecting public health, as the bacterial cause of disease began to be understood. Domestic animals and people lived in close quarters, escalating the potential for the spread of horse-to-human communicable diseases like glanders. In an increasingly densely populated city like Hoboken (which saw its population rise from 9,659 in 1860 to 37,721 in 1885 to 70,324 in 1910) such concerns were especially pronounced. The dean of the New York-based American Veterinary College was known for encouraging graduates (including some who moved to Hoboken] to become sanitarians or public health specialists. New Jersey vets began to initiate changes in milk and meat inspection; and in 1881 the New Jersey Board of Health became one of the first state agencies in the country to employ veterinary specialists empowered to kill or quarantine animals exposed to contagious or infectious disease. The Veterinary Practitioners' Club of Hudson County, a local association of NJVMA, was formed in 1907 to address local issues including "zoning ordinances regulating veterinary hospitals, illegal and unfair practices, fees, local meat and milk inspection, and employment of vets by municipal and county governments." New Jersey law regarding veterinary practice had already been strengthened in 1902 to allow for the establishment of a board to assess practitioner competency It was authorized to give oral or written exams on subjects such as veterinary anatomy, surgery, obstetrics, pathology, bacteriology, pharmacy and meat and milk inspection. The practice of veterinary medicine largely revolved around the horse until the introduction of the motor vehicle. Veterinarians who stayed in cities after the replacement of the worker horse with automobiles and trucks would have to shift their care to small companion animals. (See the Companions & Family section of City Animals, pages 55-59, for more on this shift.) Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals In large part, the value of "the noble horse, which is so important an agent in civilization," and the cost of cruelty and ill treatment, inspired New Yorker Henry Bergh, a "gentleman of means," to found the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1866.11 Bergh biographers refer to a scene he'd observed earlier, while on diplomatic post in St. Petersburg Russia, as an influence on his thinking about humane treatment of animals Passing in his carriage, Bergh saw a teamster's horse and wagon had become lodged in mud and the driver was savagely beating the trapped horse. Bergh directed his Russian-speaking driver to tell the man to stop-an intervention (on behalf of a beast) said to be unheard of in that country When Bergh's post ended in 1865, he traveled to the United Kingdom and met with the Earl of Harrowly, head of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, which had been founded forty years prior. Fired with purpose and awareness of the advances of British anti-cruelty predecessors, the socially well-connected Bergh began, on his return to New York, to gather signatures of supporters of an American S.P.C.A. His pro posal was enthusiastically received by many: There was already some opin ion among prestigious New Yorkers that favored a change in the treatment of animals. (Indeed, American society had already significantly changed its perspective toward animals, legal scholars note, as the 19th century began ==== page 25 ---- [caption photo left] Henry Bergh, founder of the ASPCA. Courtesy of the ASPCA. ---- with laws "viewing animals as items of personal property not much different than a shovel or plow," and had advanced, during the first half of the century, to begin recognizing "an animals' potential for pain and suffering was real and deserving of protection against its unnecessary infliction"- though such protections were limited to commercially valuable animals, not wild animals or dogs and cats.12) The publisher of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper printed a series of drawings in 1865 showing animal cruelty. A New York street scene sketched by illustrator Albert Berghaus and entitled "City Enormities-every brute can beat his beast" depicted several men in caps wielding whips and clubs against a horse harnessed to a cart. A policeman appeared in the background, standing at the curb, watching, with his arms crossed. Frank Leslie accompanied this image with an editorial, "The Brutalities of the Town," in which he announced: "Our first page offers an illustration of every day sights in New York, one of those brutalities that there is apparently no law for... We do not claim cruelty to animals as something patent to New York. Unfortunately it is not..."13 Henry Bergh recruited to his cause an impressive range of powerful individuals, including several Civil War heroes, a Catholic Archbishop, millionaire John Jacob Astor, editor-poet William Cullen Bryant, editor and publisher Horace Greeley, manufacturer Peter Cooper, and attorney John T. Brady, who drafted a charter for the S.P.C.A. to be recognized by the New York State legislature as a state corporation. The legislature-no doubt persuaded by the influence of Bergh and his associates-granted the charter in 1866 despite opposition from horse-car companies and abattoirs that feared (correctly) that the new organization would interfere with their operations. Following the British model, Bergh made sure his new organization had enforcement power of "all laws which are now or may hereafter be enacted for the protection of animals and to secure, by lawful means, the arrest and conviction of all persons violat- ---- [caption illustration upper right] Top right: "City Enormities - every brute can beat his beast," Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, October 28, 1865. Picture Collection, The Branch Libraries, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. ==== page 26 ing such laws."14 Brady then drew up a pioneering anti-cruelty law, which Bergh succeeded in getting passed. It proclaimed: Every person who shall, by his act or neglect, maliciously kill, maim, wound, injure, torture, or cruelly beat any horse, mule, ox, cattle, sheep, or other animal, belonging to himself or another, shall, upon conviction, be adjudged guilty of a misdemeanor. The law required adjustments, secured in 1867: Bergh saw the need soon after the passage of the 1866 Act to address the abandonment of work animals; to apply the protective legislation to "any living creature" (such as dogs and cats), not just commercially valuable ones; to broaden the list of illegal acts to include a new section making animal fighting illegal as well as the ownership and keeping of fighting animals; to cease requiring acts to be "malicious" (thereby shifting the focus from the perspective of the person to evidence of what happened to the animal); and, among other provisions, to add a remarkable section that specifically provided A.S.P.C.A. representatives with the power to arrest violators of the law. With Bergh's New York law of 1867, note legal scholars David Favre and Vivien Tsang in their Detroit Law Review study of 19th century anti-cruelty laws, "an ethical concern for the plight of animals was transformed for the first time into comprehensive legislation." It became the model for anti- cruelty laws (criminal laws and chartered state Societies for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals) adopted across the nation. Bergh soon became known in the New York press as "The Great Meddler" for his intervention in various acts of animal cruelty in the state. And even though his legal powers applied only in New York, he could not resist agitating on behalf of animals in New Jersey. Animal advocates here were just as eager to solicit his aid after reading about his accomplishments. Within months of establishing the country's first humane society, Bergh received reports on animal cruelty in Hoboken. "A German lady, Mrs. Antoinette Otto," who became a "Patroness" of the S.P.C.A., wrote: "Would to Heaven that such a Society as yours existed in the State of New Jersey," because: Here in Hoboken the cruelty to animals-especially to that noble animal the horse-is outrageous-starved to skeletons-covered with sores from the blows of their inhuman drivers; they are forced, beyond their strength, to pull their heavy loads, on loose ground, and up steep hills. Some of these poor horses have wealthy owners; yet during the winter, numbers of broken-down creatures are turned out on the meadows to die a cruel and lingering death, by freezing and hunger1.15 The perpetrators of such acts, she believed "to be in the employ of Mr. E.A. Stevens," a member of Hoboken's founding family (whose bequest later helped establish Stevens Institute of Technology.) Mrs. Otto suggested "a 'reminder' of that fact from you will certainly have a most salutary effect- for Mr. Stevens cannot possibly be aware of the inhumanity of his employees." Bergh wrote Edwin A. Stevens that same day, citing in his December 7, 1866, missive "an extract from a letter just received from a person of high respectability residing at Hoboken" and implored Stevens to found a New Jersey branch of the humane association "and earn the blessings and applause of your fellow-countrymen." (Each chapter of the S.P.C.A. is distinct as states make their own animal protection laws.) But Stevens, in his dotage (he was then 71 and died two years later) did not sign on for this mission and there is no record of a reply to Bergh's request. Henry Bergh peppered New Jersey state legislators' mail with copies of the New York S.P.C.A. charter, by-laws and other aids he thought might be useful in forming a Garden State society with protective legislation. And he used the Hudson County press to promote public outrage over local abuses, including this 1868 letter to the editor of the Jersey City Evening Journal, objecting to the abandonment of a horse "made to draw nine tons of coal from Hoboken to Jersey City": The facts, as near as I can get them are these-On Saturday [April 11] the horse... while struggling beneath the last load, which the poor beast had done his best to transport for the benefit of his unfeeling master, fell where he now lies, in the vain effort to go further. The driver, ignoring the right of the animal to fall and die, until he had done with him, beat him with his whip, ==== page 27 but finding that this did not revive the abused creature, seized his cart rung and pounded away, but with no better success. For it was nature and not the animal that refused to go further. Seeing that all he did in the way of torture could not impart to his prostrate servant the power of going further, he took off the harness, removed the cart and left him to perish in the bitter snow storms, which you are aware, continued at intervals during Saturday and Sunday; and at 9 o'clock this Monday morning he was still there where he fell, pawing the ground, and groaning with agony, without food or shelter - and not even a friendly hand willing or with power to end his sufferings. Bergh had given a letter to an intermediary to hand to the Captain of Police of Jersey City The animal advocate said he had politely asked the Captain to "relieve the poor beast in some way-by death, if past recovery," but the policeman refused to do anything. He threw the letter back at Bergh's colleague "with language of the most abusive character." The problem, Bergh pointed out with bitterness, was that "...the animal in question was insured -hence, although disabled past recovery no one will terminate his sufferings, because of the miserable money involved."16 Letters to the Livestock Insurance Company in Hartford, Connecticut, were soon issued by the indefatigable A.S.P.C.A. founder, but without immediate result. Bergh's anti-cruelty arguments-especially those on behalf of the horse- did find vigorous support among editorial writers for the Hoboken-based Hudson County Daily Democrat. Referring to New Jersey's first round of legislation to incorporate a New Jersey Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals-modeled after New York's laws and passed in April 1868 with multiple amendments to follow-writers for the Daily Democrat called for "animal abusers [to] be arrested and made an example of," questioned why nearly starving horses and mules were made to work in the city and pointed out that overloaded teams from New York City daily struggled on Washington and Hudson Streets. "Many of the horses attached to dirt wagons, employed on the improvements in the vicinity should claim the attention of some 'Berghite,'" one news item concluded.17 A Hudson County branch of the S.P.C.A. formed in 1873, though little is known about its activities. But a report of the New Jersey Society about its formative years indicates that anti-cruelty activists in the state were often focused as much on the moral state of humans who abused animals as the suffering of "dumb" (a then common term for "speechless") animals. As a New Jersey S.P.C.A. member reported on the foundation of the society: The better part of the community have not been slow to perceive that the humane intentions of the Society fully carried out, tend not only to prevent the infliction of cruelty on brute creation, but also to curb such vicious propensities and ferocious instincts in other directions, as are frequently exhibited among the lower orders of Society.... It is indeed self-evident, that the practice of strict humanity toward the inferior members of God's great living family on the part of one who has hitherto been cruel in his treatment of them, is a most important step in the purification and refinement of his own character. Like their New York counterparts, each member of the New Jersey Society who wore a badge was "legally permitted within his own district to exercise supervision over the natural rights of our dumb animals and [was] empowered to cause the arrest of all perpetrators of inhuman acts;" the New Jersey S.P.C.A. claimed its members had accomplished "an improvement in the condition of horses on our horse rail roads, canals and public highways," though without the persistence of Society representatives, they conceded, many cases were dismissed with a reprimand or word of caution, and no penalty was inflicted. Although certain animal-related laws of the period-requirements that clean water be publicly available for horses, for example-have become less relevant in the century since their passage, and many aspects of animal welfare have been improved into the 21st century, animal law scholars note that the legal relationship of humans and animals, established in the 1860s and 1870s by Bergh and his colleagues, remains the legal base today. Laws regarding children and married couples, for example, have fundamentally changed since the 19th century-a reflection of societal changes and shifts in perception-but the laws regarding animals have not similarly advanced. They are still property and "the legal system has shown itself to be loath to penalize a person for the way in which he uses his property."18 ==== page 28 From Carriage-Makers to Car Mechanics: The Kostelecky Family of Bloomfield Street The lives of city horses may have been most changed by technological inno-vations introduced at the turn of the last century. Electricity was available in Hoboken from 1886, when the city's chief engineer turned a switch at the local electric plant. The advent of electric power, along with the introduction of the combustion engine, dramatically altered city life, including an increasing withdrawal of horses from the urban workforce. With this withdrawal came the waning and eventual disappearance of entire professions associated with equines, including carriage-, harness- and saddle-makers; carriage-painters; coachmen; horse-shoers; livery keepers and wheelwrights. Although some historians cite the 1890s craze for bicycles as the beginning of the decline in livery stables-about 1 million bicycles were in use in the U.S. by 1893 and Hoboken, like most cities and towns, had a track for "velocipedes" during that period-in this city, at least, the introduction of the automobile brought the most dramatic changes to residents.19 The 100-year history of the Kosteleckys' family business on Bloomfield Street-from carriage-makers to car mechanics-indicates the impact of tech-nological innovations on Hoboken humans and horses, and shows how such innovations initiated vocational transformations.20 Born in Czechoslovakia in 1863, Joseph Kostelecky trained as a blacksmith's apprentice before emigrating to America and settling in Manhattan. There he gained experience as a ---- [caption photos upper left and lower right] Above: Joseph Kostelecky, successor to Miller & Co., Painting & Trimming/Carriage & Wagon Mfr., General Blacksmithing, Hoboken Rubber Tire Works, photo circa. 1880. Kostelecky is wearing a derby. Right: Joseph Kostelecky making carriage bed and assembling pre-fabricated spokes, circa 1921. Both photos courtesy of Florence Quinzel and the Kostelecky family. ---- carriage-maker. By the 1880s he had moved to Hoboken with his new skills, taking over the business of a retiring carriage and wagon manufacturer at 224 Bloomfield Street. Over the course of his 76 years, he would marry twice- his first wife, Josephine, died in 1897-and father nine children, eight of whom would survive into adulthood. Three of his four sons would work in the family business, refitting the shop and their skills over the years. Kostelecky next purchased the 218 Bloomfield Street property, which he razed to the ground so he could build a ground-floor shop with a dwelling above. Two of his sons, Joseph [Jr.] and Louis, after serving in World War I, acquired 216 Bloomfield with the express intention of becoming auto mechanics-by then a potentially profitable undertaking. Until around 1911, cars were mainly considered an amusement for the well-to-do; carriage-drivers, who continued to dominate the roadways during the early years of automobile development, complained about cars because their horns and lights frightened horses on the roadways. By 1914, however, the mass production of cars was in full swing, with about 2 million vehicles in the U.S., and macadam and cement highways were proliferating to accommodate the popular new method of transportation.21 The Kosteleckys, who opened their auto-repair shop around 1920, maintained 216 Bloomfield as an auto-body shop and parking garage until the late 1960s. The 218 Bloomfield property continued to serve Hoboken owners of horse- drawn carriages into the 1920s. In a circa 1921 snapshot, Joseph Kostelecky is seen making carriage beds and assembling pre-fabricated spokes. Horse-drawn cart could be seen on Hoboken streets into the 1940s. Frederick, a son from Joseph Sr.'s second marriage (to Frances) took over the 218 Bloomfield Street shop from his father. He focused on auto repairs and detailing until the 1980s, when he took down his sign and retired, ending a century of family service to Hoboken's horse-drawn and horseless carriages. ==== page 29 Society for the Prevention for Cruelty to Children Henry Bergh not only made U.S. legal history by forwarding legislation to prevent cruelty to animals, he helped initiate legal protections for children, who were, during the 1860s and 1870s, subject to ill-treatment, exploitation and overwork, like the four-legged beings Bergh first sought to protect. Working with attorney Elbridge Gerry and with the support of philanthropist John D. Wright, he put forward a proposal to found and organize the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NYSPCC), the world's first child protection agency. Incorporated in 1875 with Wright as its first president, the NYSPCC's creation followed revelations to Bergh a... [truncated due to length]

![pg [1] title](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/f1250a40-fa69-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdLdpT.tn.jpg)

![pg [2]](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/f2563740-fa69-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdLedf.tn.jpg)

![pg [3] contents](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/f3876440-fa69-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdLeu5.tn.jpg)

![pg [4] introduction](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/f4b8df60-fa69-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdLf4K.tn.jpg)

![pg [12] Neighbors](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/fe43a6f0-fa69-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdLjec.tn.jpg)

![pg [19] Workers](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/069ca540-fa6a-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdLn29.tn.jpg)

![pg [31] Food & Clothing](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/14ee43b0-fa6a-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdLtpg.tn.jpg)

![pg [36] Spectacle & Sport](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/1ae4c0f0-fa6a-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdMwDa.tn.jpg)

![pg [46] Pests & Strays](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/26d1e280-fa6a-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdMBUN.tn.jpg)

![pg [55] Companions & Family](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/318dd710-fa6a-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdMGIW.tn.jpg)

![pg [58]](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/35222160-fa6a-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdMHip.tn.jpg)