Collections Item Detail

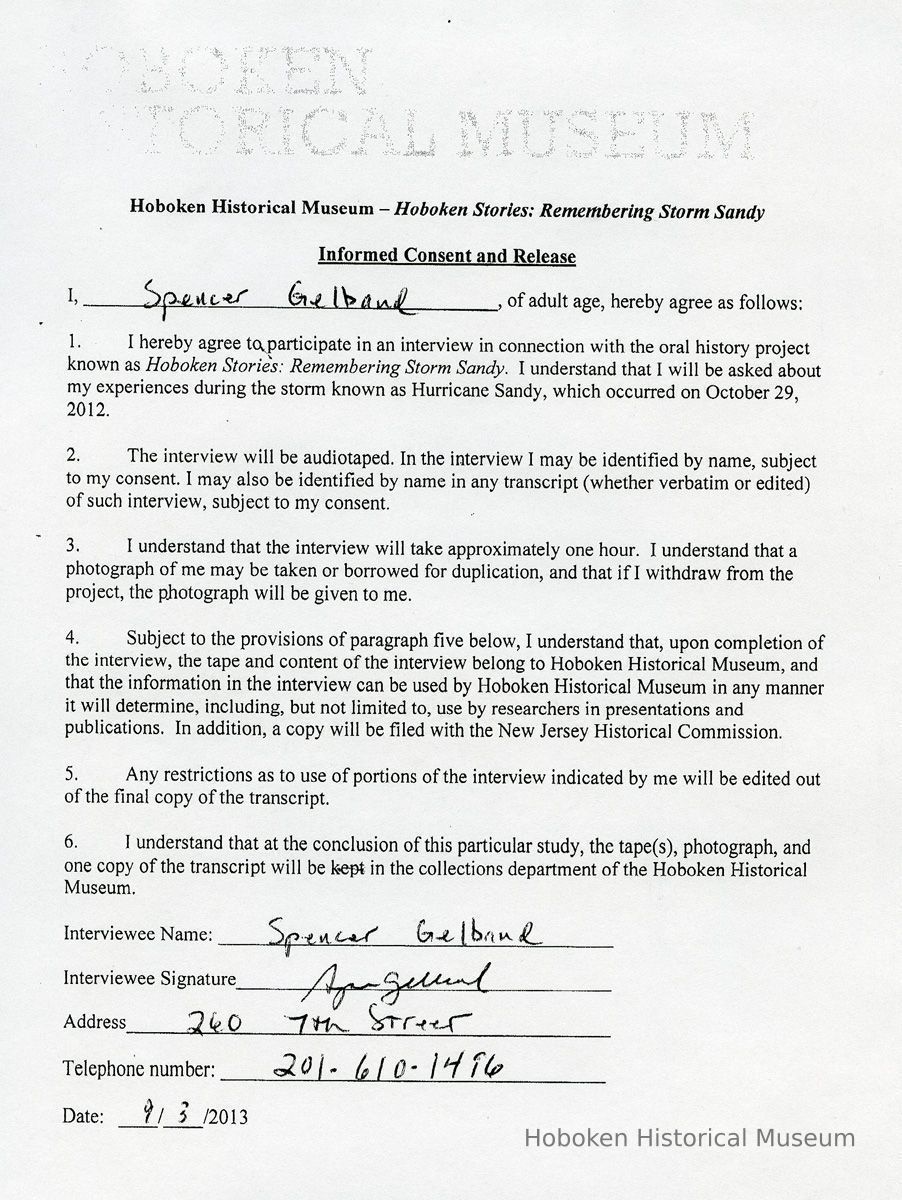

Oral History Interview: Spencer Gelband, Sept. 3, 2013. Hoboken Stories: Remembering Storm Sandy.

2013.039.0010

2013.039

Staff, Produced by

Produced by Staff

Museum Collections

2013 - 2013

Date(s) Created: 2013 Date(s): 2013

Notes: Archives 2013.039.0009 THE HOBOKEN HISTORICAL MUSEUM HOBOKEN STORIES: REMEMBERING STORM SANDY INTERVIEWEE: CARMELO GARCIA INTERVIEWER: ALAN SKONTRA LOCATION: 400 HARRISON STREET, HOBOKEN, NJ DATE: 3 SEPTEMBER 2013 Track #1 AS: Okay. First question. What is your connection to Hoboken? How long have you lived in the city? Where do you live? Who do you live with? And what is your profession? CG: My connection to Hoboken is that I'm a product of the Hoboken Housing Authority community. I serve as the executive director of the Hoboken Housing Authority. I live in Hoboken. I'm born and raised in Hoboken. I reside at 711 Bloomfield Street, on Seventh and Bloom. I reside with my family -- my wife and three beautiful children, and two beautiful dogs. Do you want to know their names? Which are Leah, Jill and "Lenise," [phonetic] and my two dogs are Hudson and Willow. So my connection to Hoboken is that I have served this city with distinction, in the capacity of a city official, as the director of Health and Human Services, from 2001 through 2007, and later came on board to the Hoboken Housing Authority, in August of 2007. I actually was here during the crisis and tragic situation that we had on September 11th, serving as director of Health and Human Services. I was fortunate to help many people through the health department and human services at the time, and currently we are talking about two disasters that we experienced, which were Irene and Sandy -- but more so Sandy. So does that answer all those questions? AS: Yes. CG: Good. AS: Give us a background on the Housing Authority. Approximately, how many people live in the Authority? Where, approximately, are the Authority buildings? What's the general condition of the buildings, in terms of how many floors? Details like that. And, approximately how much personnel do you oversee? CG: Okay. Was that enough on the first question? Okay. I didn't know how much you wanted me to go into detail. Okay. With respect to that question: The Hoboken Housing Authority is a community that has six developments scattered throughout the city of Hoboken. It's 1,353 units. The buildings are designed in X-shaped style. You have three developments that are designed for senior-citizen and disabled persons. One is in Fox Hill Gardens, which is 311 Thirteenth Street. There are 200 units in that building, ten stories high. The other is 220 Adams, which has 125 units. Then you have 221 Jackson, which is 125 units. These three sites are located, geographically, in the west part of the city. The west end; what we consider the southwest end of the city is 221 Jackson. Two-twenty Adams is more southwest but midtown. Then you have Fox Hill, which is uptown. Then you have Christopher Columbus Gardens, which are two ten-story buildings, seven-story buildings, that are ninety-seven units, in the middle of the city, which is on Eighth Street and Ninth Street, between Jefferson and Adams -- 460 Eighth Street and 455 Ninth Street. Those are the younger buildings. They're brick and mortar, predominately. All the mechanicals are in the basement of the buildings. Then you have the most effective buildings, which are the aged buildings that have the obsolescence, which are the ones in the west end of town, which are considered to be Andrew Jackson Gardens and Harrison Gardens. Both of these developments comprise of 806 units in total. The Harrison Gardens development has ten stories. It is, again, another X-shape design in its construction -- brick and mortar -- and these are the first buildings that were built in the city of Hoboken for public housing, during World War II, post-World War II, in 1948 and 1949. The Housing Authority has, in total, fifty-two buildings, Pretty much ninety-five percent of the buildings were submerged during Sandy, as far as its mechanicals, because when they designed these buildings and constructed them, all the mechanicals were on the ground floor -- which, as we know, the new FEMA flood-plain guidelines are thirteen feet. These buildings were six feet, back then, before the new guidelines. So, unfortunately, it had a history in which flooding has affected the southwest corridor of the city. The quadrant here, or this area, indeed, when the water travels from the northeast sector of the community, down to the southwest, it always hits the lowest point, which is where we sit, currently, today. This administration building -- 400 Harrison -- is in the heart of that lowest point. During Sandy, the water took six days to recede from this area. One of the developments -- Harrison Gardens -- was held hostage because of the fact that the water was at least five- to six-feet high. The basements were filled with flood waters of ten to twelve feet high. So that, in architect form, is your structure of these buildings, as I just described them. AS: Describe the typical Housing Authority resident. CG: Before I go to that, Alan, let me just share another point of the conditions. You mentioned the conditions. We had conducted, in 2009 to 2010, a physical-need assessment, which the professionals, architects and engineers, were able to discern that these buildings in this part of town -- the west end, meaning Harrison Gardens and Andrew Jackson Gardens -- definitely should be considering an overall, simply because of the age of the buildings and the design. They're not ADA complaint. They don't have enough light and air ventilation. So we have been confronted with the challenge that after Irene, and then, of course, all the flooding in the past, that these buildings continuously, in the basements, as far as the mechanicals, continue to receive water that creates corrosion, especially with the salt water, post-Sandy; and, also, it leads to rust and deterioration to the systems. So when we're talking about the condition of the buildings -- there was a period when these buildings did not receive the proper treatment and attention that they required, from a preventive maintenance standpoint and maintenance management standpoint, when it boils down to a property management plan. So that leads me to share with you that these conditions are not conducive to sustain continuous disasters or continuous hurricanes. That's why we have a Vision 20/20, which is a transformation and sustainability plan that we're looking to pursue, to build our first anti- or Sandy-proof building, as I call it, so we can start to reconfigure the housing stock in this area, with a newer housing modernized, that is Sandy-proof, allows for it to be built above the thirteen-foot flood-plain guidelines, and would create an environment and neighborhood that has all the accoutrements that a community of this magnitude should have. So when you ask me about the typical resident, I would say that we have blue-collar, working-poor, as well as residents who are elderly-disabled. The typical resident is a family of pretty much mom, children. You have senior citizens and disabled persons, then you have individuals who are looking to have that self-sufficiency, which is the ultimate goal of the Housing Authority -- to have everybody provided with the self-sufficiency road map that would allow them to graduate, and make better for their family as well as, with our cooperation, improve their quality of life; to transform the culture; to break the cycle of poverty, as well as to give them hope and a better way to live. So that is one of the goals that we've always pursued, because the typical family or resident of the Authority is a person who loves the city like I do; who understands the need for civic responsibility; who likes to get involved in the civics of this community; and who wants to see progress for the people of this community, who, for decades, were given negligent treatment, per se, in the management of these buildings, and in the care. It goes along the lines with our mantra that our people don't care how much you know, unless they know how much you care. So that is the typical person or family within the Housing Authority. It's a hard-working person or family. It is those who are underprivileged; those who have special needs; those who are the most needy, I would say, in this community. That's who we serve, and that's who we continue to try to give a better quality of life. AS: When did you first hear the words "Hurricane Sandy." CG: Interestingly so, Hurricane Sandy hit that Monday, and it's a memorable, vivid event that still plays in my mind. We heard about it the week before that. We were listening intently as to what could be happening, as the development of Sandy was coming to fruition, into it being eventually Super Storm Sandy. AS: What did you expect the storm to be like? CG: We heard everything with respect to the possible surge from the Hudson River. We heard everything. That it might just be passing us by. It was something where we prepared the week before. We had that weekend, in preparation for that Monday, on Saturday an emergency resident meeting to educate residents to basically help them prepare and plan for the worst. So we were praying for the best but preparing and planning for the worst, and that Saturday, before we met with the residents, we said, "Here's what our intent is. Here's what our emergency evacuation plan is. Here's what our emergency recovery plan is." But, as we know with our residents in the Housing Authority, it is difficult for them to just get up and go, because they do not like to leave their apartments. They do not like to leave their homes. They basically are troubled in wanting to leave their homes, because of this sense of pride in ownership that they have in their apartments -- and they don't have anywhere to go. While we deploy an emergency evacuation plan, and an emergency disaster plan, we basically try our best to get them out of their apartments, if we know we're going to have the kind of waters and the floods that we had, but we know from Irene that they don't want to leave. Therefore, we have to shelter them in their units, and do our very best as an administration, as a management organization, to shelter them in their units, and provide a safe environment, to the best of our abilities, relying on the Office of Emergency Management. We're not relying on our counterparts; we're relying on a team effort to get that goal accomplishments. Therefore, that is how we were preparing for Sandy. What I expected that night -- at about 9:00 that night we thought we had survived the worst. It was about 10:00, and we were here, with all of our -- what we did was, we have all these pumps, and we basically put hoses to the pumps so we could pump the water out into -- over the light rail into the Jersey City area, which is an uphill kind of setup, so the water can't traverse back into the Authority. So we knew, in preparation, that we had to remove our caps, prepare with respect to putting hoses to all of our portable sump pumps and portable pumps, and we basically planned -- we fastened every item in the buildings, because we knew the winds were going to be about eighty, ninety miles per hour. We had tested all of our generators. We had run down the check list, which is our preventive emergency disaster plan check list. We went and checked all the doors; made sure they were all fastened. There were no windows that were loose, or there was nothing that was open. Elevator rooms, we checked all the roofs, we basically went to all the basements. We made sure that we made a way, so the water could probably be pumped out. The sewers -- we made sure that the sewers had been emptied out and had been flushed through, so that would not create a backup in the buildings, because that's the tendency that happens; to get backups that go into the first-floor apartments of the tenants. So you have to take the caps off of the plumbing system, and you have to ensure that your sump pumps are working -- which we tested. Our generators, sump pumps, the emergency lighting, the life safety equipment. We made sure all our fire-lungs were in order. Everything, in fact, was prepared for that event. By that night, at 10:00, we were all here, my team and I, and we thought we survived. We had maybe about a foot of water, and we thought we survived. Then, lo and behold, as I was running out, rushing out to Fox Hill -- because I got a call that our generator -- that our lighting went down because of the transformer that blew up in the northwest corridor of the city, which feeds power to the Fox Hill buildings, at the 311 Thirteenth Street building -- the generator, with the heavy winds at eighty, ninety miles per hour, was now, into the late hour of the day, was blowing drastically. That generator sits on the rooftop of the Fox Hill building. When we left, we thought, "Okay. We had survived the worst." Lo and behold, one of my employees sends me a video of the water raging down, like the rapid river, just coming down forcefully, that night, onto the Housing the Authority, in the Harrison Gardens and Andrew Jackson Gardens area. It was unbelievable. At this time, I am now at Fox Hill, up in the northeast corridor of the city, northwest corridor of the city, and then is when we realized, "Holy cow! We're in for a tumultuous and tormenting event." What happened was -- we were dealing with the emergency at Fox Hill. Myself and my electrician went up on the rooftop to see why the generator -- it had turned on, and then it blew. What happened was, when the transformer at PSE&G blew, it blew a power surge through our generator and transfer switch, and lo and behold, what happened was -- Track #2 So what happened then was the following. Once we heard that this rapid river of water was flowing into the Housing Authority community, we had already done our best to prepare and embrace ourselves for what would happen here in the west end of town, in Jackson and Harrison Gardens. In the meantime, I was busy at Fox Hill Gardens, where we worked until about 3:00 in the morning to get that building back on. Unfortunately, what transpired was that while we were on the roof, my electrician and I, he went to check the generator and manually set it, and the winds were at about ninety miles per hour. What happens is, the generator sits outside of the secured area. So you've got to go outside the gates -- which is really not secure, because it has no gate around the edge of the building. So here we are, holding onto each other, because the wind is blowing so heavily, and it feels like you're being smacked. And we're on the rooftop, so it's even stronger on the rooftop, because of the height, and here we are holding onto each other, where my electrician is trying to reset that generator. Lo and behold, the wind was so strong -- the panel went flying. It busted our water pump in the actual generator. I thought at that moment -- I had to make a conscious decision, because of the safety of the situation. I pulled him away, we pulled out, and let me tell you -- and he's about a "buck-ten" -- him and I holding each other together -- as far in weight, he's about 110 pounds, him and I holding each other, on that rooftop! It was instinctive that we went to act on the situation, before the FD could come, or anybody else. Because, remember, at this time, they're dealing with the fire up at the transformer station, that PSE&G just found out blew. So now the water is racing down the way. We've already braced ourselves for the worst down here. I'm up there, trying to get this building back on line, with its emergency lighting. We're trying everything, going through floor-by-floor. My staff immediately, my team converged into going floor by floor, door to door. We went to the manager's office to take the list out, of the people that we knew had life-safety apparatuses, that require oxygen tanks or whatever it was. We began to identify those individuals. Then the EMT came, and the Fire Department came. We had already, previously, set up, in partnership with OEM, the annex shelter at Wallace School. Fortunately, we were able to convince certain elderly and disabled individuals, residents, who we basically knew should have been outside the building, in the satellite shelter which was next door, at Wallace School, which is what we did. After that, fortunately, we began to pull out all our flashlights. We began to work around the clock, to try to get that building restored, and made sure all the residents were not alarmed, and that the anxiety and the crisis did not put any additional stress, that would lead them to get sick, or lead them to get, god forbid, in a worse condition. So we stayed in that building. Because at this point, now, you couldn't travel back to the Housing Authority buildings in the west end of town. You could not travel, because the water was flooding and immediately was just building, building, building, where I had one of my guys -- the superintendent of maintenance -- who slept in the Fox Hill community room. I stayed there until about 4:00 in the morning, then had to come back after making an assessment. I knew I had to come back as early as 6:30. So we were really around-the-clock on two-hour and three-hour minimal sleep. Bear in mind that, at the same time, Alan, in my own home, I had gotten water in my ground-floor apartment. I had no lights. So my whole family -- that's why I had to go back; to check on my own family, to make sure they were fine without the electricity. But we had already gone through the appropriate checklist, to make sure we had all the tools we needed to survive, in the event that this thing was going to be carried out for a long period of time. Which is what we did. Then the next morning, I had to literally walk from Fox Hill -- 311 Thirteenth Street -- we could not use our vehicles to travel down into Christopher Columbus Gardens, which is on Eighth and Ninth, because the water was at least four feet high. We had to walk -- myself, my superintendent of maintenance, and my quality-control officer -- we all walked. We had our fisherman's suit on. It was pretty much one of those scenes where we have our flood suits, we're prepared. We walked in the water (I have pictures), where I even found an orange fish that had come in from the river, and other things. When we walked to Christopher Columbus Gardens, it was one of the scariest scenes, because at Fox Hill the water did not come up onto the building. It did not go into the building. It remained at street level. But it did wash up all the debris onto our ramp, basically, and you could see clearly like a tornado had hit, or like a hurricane had hit, where you had debris all over the place. All the garbage from outside had come in. You had vehicles that were floating. As we walked down into Christopher Columbus Gardens, it was like a sea of green, and the sea of green was the anti-freeze. And we had oil that had been discharged from the compactor rooms. We had alarms going off, haywire, because the controllers in the basement were now submerged. It required immediate, immediate deployment and ingenuity of necessity, to basically invent different ways to get the buildings up to par with at least a safety standpoint of restoring the generators, to provide the emergency lighting; making sure that immediately -- because a lot of these generators were affected by not just the water but the salt that came in the aftermath of it. But lo and behold -- and then you had some rodents chewing away at the wires, because now, guess what -- they were disturbed in their environment, right? So they're going to go and travel, and you're going to get the type of rats and stuff that are going to come out, and they're going to be chewing away at these wires, in these areas that are exposed to them. So we were combating a lot of adversity and a lot of challenges were presented to us. But ultimately, I must say, we were prepared with a plan and we took action. We were on the ground, boots on the ground, right at the minute, at the second, of every hour that we needed to be there, to provide the same environment for our residents. We immediately walked down from Christopher Columbus Gardens after I did the assessment of those two buildings, and that was, like I said, a sea of anti-freeze. It was basically a sea of green. I have pictures to demonstrate that -- which, at that point, you had a mixture of Class 3 water. You had, basically, black oil; gasoline; anti-freeze; you name it, it was in that water. It was a situation where you acted on instinct. You were thinking about your people. We were thinking about our residents. That was a selfless act by all of my guys, where the team was prepared. Because beforehand we had huddled, we had given them the action plan, and we had let them know, "This is what we intend to do at each development," to insure that the residents would be safe. So lo and behold, what happened, Alan -- at that juncture we went from Christopher Columbus Gardens, after that building, after assessing it, doing whatever repairs or tweaks we needed to make to the generator -- to make sure, we went floor by floor, to make sure everybody was safe and make sure everybody had resources available to them. Again, we were sheltering the residents in their buildings. Then we went down to Andrew Jackson Gardens and Harrison Gardens, where we had to walk through the Eighth Street side, and come in through the light rail area, which is a little bit more elevated. So we walked through the Eighth Street light rail area to get into the housing, on foot. All along, we were walking on foot, because we could not travel into these areas by vehicle. When I got into this area, we had already set up -- pretty much we had a food pantry; we had ice, because we knew from Irene that residents with diabetes would need ice. Now that the power was gone, and residents were nervous, and there was a lot of anxiety. The generators were working -- thank god we had already tested them. Some generators tripped because of the salt water, because when the water hit it splashed against, like a wave -- it hit against the walls of the building, and splashed onto the generators. So the water got into some of the generators. Of course, the controllers -- all of our controllers, because of the design of these buildings -- you don't have height in the ceiling, to raise everything up in the appropriate way that it should be -- although now we've mitigated, in certain mechanical parts that we felt we can, or certain controllers that we felt we can -- but you don't have enough ceiling height, because of the ways the buildings are constructed. So what happened was a lot of the controllers got damaged, got wet, and the salt was eating away at it. But at this juncture, from that moment, I had to immediately establish the command center over in 221 Jackson. Everyone was moved out to 221 Jackson. We had a plan where people would come in if they could get into the city. Those who were residents of ours -- because we have an emergency resident personnel, which is a team of superintendents who are trained in the area of emergency preparedness and emergency disaster relief, as well as these kinds of disaster crisis situations -- so it's an in-house, kind of Office of Emergency Management CERT team. It's like our in-house guys, who are trained in these areas. So we began to immediately -- the first thing you had to do was assess the situation. The second thing is, take action and repair what you could. The third thing is -- which we were fortunate -- I was able to have my disaster recovery company always on hand, to address and help me with the pumping out of the water. Track #3 CG: So, Alan, to continue -- if I can -- what happened at this juncture -- now, at this point, Alan, understand that during the nighttime, when, in fact, the next day, when we were here on site and the assessment was made, I had already -- my partners -- you have strategic partners. Any property-management company, particularly the Housing Authority, should have a strategic partner, which is a disaster recovery company. So we had a couple of companies on standby who (a) would provide us generators, if, in fact, we needed a backup generator. What I did was, I was proactive and innovative in getting what we call light towers, because we did not have any light in this area. But before we get to that point, we had to have rapid response and [unclear] basically, pump the water out. So they had these water buffalo rigs, and they're designed with a hose, a suction and a hose, that basically pumps the water out, like three thousand gallons per minute. It was just incredible, watching these massive machines at work. But the biggest problem we had was that the water -- unfortunately, because the floodgates were closed in the sewer system, would come back out. So the only water that we were successful in pumping out was over the hill into Jersey City, but the other water that would go into the sump pumps, right? Would be ejected, would be circulated again, because the floodgates were closed. So what happens is, at that point you're combating against forces of Mother Nature, and you're combating against existing, pre-existing plumbing systems and conditions that really would not be conducive to manage that type of situation, and to really expediently get the water out. So it took six days for the water to recede from our area. As a matter of fact, there was a situation where the water was holding that development hostage, and when the electricity went out we had to get a back-hoe. The Fire Department couldn't even get two rigs into this area, and we had to get a back-hoe to basically remove a tenant from the third-floor apartment, who was suffering from a medical condition. It was things like that, that people did not hear about; situations where the electricity was down for fifteen to sixteen days, and the hot water and heat were unavailable. This is now October-November. It was unavailable for twenty days, twenty-one days. Remarkably, the goal immediately was to shelter the residents. To make sure that each building was safe; that each aspect of what we did was relative to the safety and the priority being the residents. Any needs that they had, such as we had a list of all those identified individuals. Before we even got to that point -- before I forget -- when it was raining harshly throughout the day, on that particular Monday, we were knocking on all the doors and giving notices out to the residents, saying that if they could evacuate, that would be something we would recommend that they do. Lo and behold, once Sandy hit we knew immediately that the deployment of our plan was to shelter the residents; was to maintain the buildings safe; to ensure that, from a life-safety perspective, all equipment would be operational; and all top of that, battle the remnants of what we saw happen. When we walked into this area of town, we had to climb -- you had to climb, literally -- using railing to climb into this area, to get into the Housing Authority area of Andrew Jackson Gardens. When I stood on the islands, the water was literally to my knees, on the island, which is already four feet above ground. This is above the street level. We had basements where you could have practically been swimming in, because the water was ten- to twelve-feet high; the markings are there. So you couldn't even get into the basement, to put anything on, or check the heaters, or hot water heaters, because you couldn't, because of the safety issue. If there is, god forbid, a cable down. We had cables that were down. We had wind that blew the cables off the buildings, and we didn't know -- we had to make sure that they were -- if we had live wire or not, if it was a telecommunication cable -- again, it was a scary situation because residents didn't know how to react to certain aspects of what now they were living with, in this crisis. What we realized in the moment was, as long as my team could reassure and reaffirm the residents that we, as the professionals, as the specialists in this area of emergency preparedness, emergency disaster and recovery, that they knew we were on the ground -- boots on the ground -- and that they saw us in action, leading by example, that they would have their fears allayed. And we did that. We accomplished that. Because it was like an army of my team, in Navy Seal fashion, that was out there -- you know what? Doing the unthinkable; really sacrificing themselves. We sacrificed ourselves. And my team -- they were courageous. It was in the line of Braveheart, right? Men don't follow titles, they follow courage. So they saw me in full-blown action where, instinctively, we were acting on things, and ingenuity, and necessity, and inventing, and basically doing [Unclear] stuff that we felt -- we had to jimmy-rig stuff in order to get power from the elevators. Then you had the residents who were trying to get power from the elevators -- remember, there was no connectivity. No one communicated to the residents. There was no communication system from the Office of Emergency Management, or those who are responsible for communicating to our residents. So our residents felt -- After the sixth day, Alan, I went into City Hall, and I'll never forget -- I went in there while all these press, post-conferences are going on, and press conferences and what have you, and I said to the mayor, I said, "You know, unless we want another Katrina on our hands, we need the National Guard in here. We need to make sure that, in fact, we get the resources we need, such as the [unclear], such as the water, such as whatever is available to my families ... [truncated due to length]

![pg [1] typical](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/7e648060-fb29-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFikqMi.tn.jpg)