Collections Item Detail

‘Open Sesame’ Just Won’t Do: Hoboken Tries to Unlock Its Cave. The New York Times online, June 26, 2007.

2007.002.0400

2007.002

Staff / Collected by

Collected by Staff

Museum Collections

2007 - 2007

Date(s) Created: 2007 Date(s): 2007

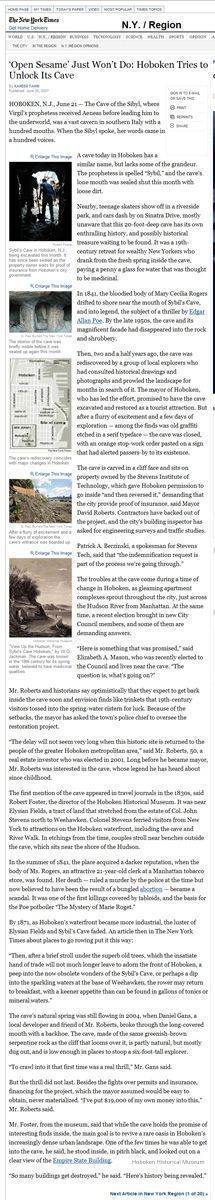

Notes: Text from The New York Times website, June 26, 2007: ‘Open Sesame’ Just Won’t Do: Hoboken Tries to Unlock Its Cave By KAREEM FAHIM Published: June 26, 2007 HOBOKEN, N.J., June 21 — The Cave of the Sibyl, where Virgil’s prophetess received Aeneas before leading him to the underworld, was a vast cavern in southern Italy with a hundred mouths. When the Sibyl spoke, her words came in a hundred voices. [Image 1] Robert Foster Sybil’s Cave in Hoboken, N.J., being excavated this month. It has since been sealed as the property owner waits for proof of insurance from Hoboken’s city government. [Image 2] G. Paul Burnett/The New York Times [incorrect, actually Robert Foster and is correct in printed newspaper.] The interior of the cave was briefly visible before it was sealed up again this month. [image 4 Hoboken map by the New York Times] The cave’s rediscovery coincides with major changes in Hoboken. [Image 4] G. Paul Burnett/The New York Times After a flurry of excitement and a few days of exploration the cave's entrance was boarded up. [Image 5] Hoboken Historical Museum "View Up the Hudson, From Sybil's Cave Hoboken," by W.G. Jackman. The cave was known in the 19th century for its spring water, believed to have medicinal qualities. A cave today in Hoboken has a similar name, but lacks some of the grandeur. The prophetess is spelled “Sybil,” and the cave’s lone mouth was sealed shut this month with loose dirt. Nearby, teenage skaters show off in a riverside park, and cars dash by on Sinatra Drive, mostly unaware that this 20-foot-deep cave has its own enthralling history, and possibly historical treasure waiting to be found. It was a 19th-century retreat for wealthy New Yorkers who drank from the fresh spring inside the cave, paying a penny a glass for water that was thought to be medicinal. In 1841, the bloodied body of Mary Cecilia Rogers drifted to shore near the mouth of Sybil’s Cave, and into legend, the subject of a thriller by Edgar Allan Poe. By the late 1950s, the cave and its magnificent facade had disappeared into the rock and shrubbery. Then, two and a half years ago, the cave was rediscovered by a group of local explorers who had consulted historical drawings and photographs and prowled the landscape for months in search of it. The mayor of Hoboken, who has led the effort, promised to have the cave excavated and restored as a tourist attraction. But after a flurry of excitement and a few days of exploration — among the finds was old graffiti etched in a serif typeface — the cave was closed, with an orange stop-work order pasted on a sign that had alerted passers-by to its existence. The cave is carved in a cliff face and sits on property owned by the Stevens Institute of Technology, which gave Hoboken permission to go inside “and then reversed it,” demanding that the city provide proof of insurance, said Mayor David Roberts. Contractors have backed out of the project, and the city’s building inspector has asked for engineering surveys and traffic studies. Patrick A. Berzinski, a spokesman for Stevens Tech, said that “the indemnification request is part of the process we’re going through.” The troubles at the cave come during a time of change in Hoboken, as gleaming apartment complexes sprout throughout the city, just across the Hudson River from Manhattan. At the same time, a recent election brought in new City Council members, and some of them are demanding answers. “Here is something that was promised,” said Elizabeth A. Mason, who was recently elected to the Council and lives near the cave. “The question is, what’s going on?” Mr. Roberts and historians say optimistically that they expect to get back inside the cave soon and envision finds like trinkets that 19th-century visitors tossed into the spring-water cistern for luck. Because of the setbacks, the mayor has asked the town’s police chief to oversee the restoration project. “The delay will not seem very long when this historic site is returned to the people of the greater Hoboken metropolitan area,” said Mr. Roberts, 50, a real estate investor who was elected in 2001. Long before he became mayor, Mr. Roberts was interested in the cave, whose legend he has heard about since childhood. The first mention of the cave appeared in travel journals in the 1830s, said Robert Foster, the director of the Hoboken Historical Museum. It was near Elysian Fields, a tract of land that stretched from the estate of Col. John Stevens north to Weehawken. Colonel Stevens ferried visitors from New York to attractions on the Hoboken waterfront, including the cave and River Walk. In etchings from the time, couples stroll near benches outside the cave, which sits near the shore of the Hudson. In the summer of 1841, the place acquired a darker reputation, when the body of Ms. Rogers, an attractive 21-year-old clerk at a Manhattan tobacco store, was found. Her death — ruled a murder by the police at the time but now believed to have been the result of a bungled abortion — became a scandal. It was one of the first killings covered by tabloids, and the basis for the Poe potboiler “The Mystery of Marie Roget.” By 1871, as Hoboken’s waterfront became more industrial, the luster of Elysian Fields and Sybil’s Cave faded. An article then in The New York Times about places to go rowing put it this way: “Then, after a brief stroll under the superb old trees, which the insatiate hand of trade will not much longer leave to adorn the front of Hoboken, a peep into the now obsolete wonders of the Sybil’s Cave, or perhaps a dip into the sparkling waters at the base of Weehawken, the rower may return to breakfast, with a keener appetite than can be found in gallons of tonics or mineral waters.” The cave’s natural spring was still flowing in 2004, when Daniel Gans, a local developer and friend of Mr. Roberts, broke through the long-covered mouth with a backhoe. The cave, made of the same greenish-brown serpentine rock as the cliff that looms over it, is partly natural, but mostly dug out, and is low enough in places to stoop a six-foot-tall explorer. “To crawl into it that first time was a real thrill,” Mr. Gans said. But the thrill did not last. Besides the fights over permits and insurance, financing for the project, which the mayor assumed would be easy to obtain, never materialized. “I’ve put $19,000 of my own money into this,” Mr. Roberts said. Mr. Foster, from the museum, said that while the cave holds the promise of interesting finds inside, the main goal is to revive a rare oasis in Hoboken’s increasingly dense urban landscape. One of the few times he was able to get into the cave, he said, he stood inside, in pitch black, and looked out on a clear view of the Empire State Building. “So many buildings get destroyed,” he said. “Here’s history being revealed.” Status By: dw Status Date: 2007-06-26