Collections Item Detail

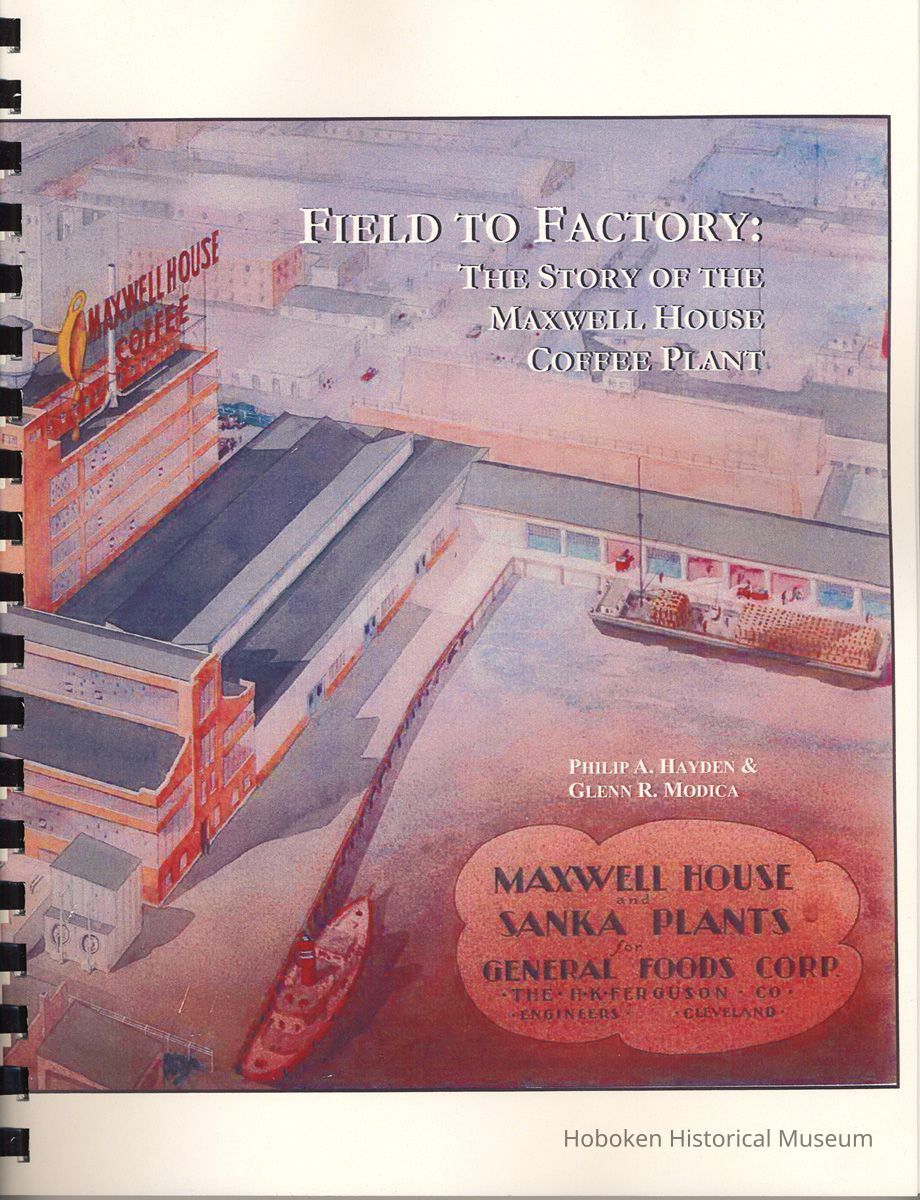

Report: Field to Factory: The Story of the Maxwell House Coffee Plant. Hayden & Modica; RGA, Cranbury, N.J. 2005.

2004.047.5001

2004.047

Gans, Danny; Vallone, George

Donation

Gift of Danny Gans & George Vallone

2005 - 2005

Date(s) Created: 2005 Date(s): 2005

Notes: Hoboken Historical Museum; archives 2004.047.5001 pg [i] Field to Factory: The Story of the Maxwell House Coffee Plant Philip A. Hayden & Glenn R. Modica April 2005 Richard Grubb & Associates, Inc., Cultural Resource Consultants 30 North Main Street, Cranbury, New Jersey 08512 pg [ii] Philip A. Hayden and Glenn R. Modica Field to Factory: The Story of the Maxwell House Coffee Plant Richard Grubb & Associates, Inc., Cultural Resource Consultants 30 North Main Street, Cranbury, New Jersey 08512 April 2005 Credits and Acknowledgements: The authors wish to acknowledge the following organizations for their expertise and help in completing this project: Hoboken Historical Museum; Hoboken Public Library; Kraft Foods, Inc.; New Jersey State Archives; New Jersey State Library; New Jersey Historical Society; New-York Historical Society; Hudson County Clerk's Office; Special Collections and University Archives at Rutgers, the State University; and PT Maxwell, L.L.C. The following individuals provided invaluable assistance: Robert Foster, Daniel Gans, James Lewis, Becky Haglund Tousey. Illustrations: Illustrations used in this work come from a variety of sources, are furnished for scholarly purposes only, and are not to be reproduced without permission. Credits accompany each image. Cover: Architectural rendering of the proposed Maxwell House and Sanka Plants prepared by E. D. McDonald, circa 1938 (Courtesy Hoboken Historical Museum) pg [iii[ CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 EARLY YEARS 3 ELYSIAN FIELDS 7 INDUSTRIALIZATION 17 MAXWELL HOUSE COFFEE 23 A NEW ERA 33 NOTES 36 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 41 pg [iv] aerial photo: Maxwell House Coffee Plant from Factory Management and Maintenance, April 1940 (Courtesy Kraft Foods, Inc.) pg 1 INTRODUCTION The site of the former Maxwell House Coffee Plant stretches along the Hudson River shoreline between Tenth and Twelfth Streets in the City of Hoboken. The factory was a marvel of its time, the largest coffee processing plant in the world, and a landmark on the western waterfront for over half a century. In 2003, as part of a plan to redevelop the former Maxwell House Plant for residential and commercial use, a team of historians and archaeologists evaluated the factory for historical significance. The investigation found the plant to be an important historic resource associated with the industrial development of the City of Hoboken and therefore eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. Founded partly on original high ground and partly on fill, the site once included key landmarks in the early history of Hoboken. Among these were pavilions, pathways, and open spaces marking the entrance to Elysian Fields, the great park to which the city owed its initial fame. The first home of the New York Yacht Club (NYYC) and its world-renowned "America's Cup" stood there too. The property is also generally regarded as the birthplace of modern baseball, a phenomenon of such significance, and one so inexorably tied to the American experience that for the game alone the place deserves special note. This story recounts the history of the site. It pays special attention to the nineteenth century, when the land underwent its most dramatic changes, and it looks closely at the role of the Stevens family, the founders of Hoboken, in shaping the tract to suit their aims. The design of the Maxwell House Plant also figures prominently, since it transformed the site and led to the initial historical study and ultimately this publication. The investigation was the result of a process by which historical, architectural, and archaeological sites are managed today. In 1966, the National Historic Preservation Act was passed by Congress and signed into a federal law. New Jersey established similar regulations to safeguard historic resources. New Jersey's historic cultural resources are managed by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection's Historic Preservation Office in Trenton. pg [2] map illustration: Bayard estate occupies the promontory marked "Hobocken" (Sketch of the Road from Paulus Hook and Hobocken to New Bridge, 1770. Library of Congress). pg 3 EARLY YEARS Settlement and Early Owners Hoboken in its earliest days consisted largely of marsh and salt meadow. The exception was a large promontory or point, rising island-like out of the grass and mud on the Hudson River's western edge. This natural garrison commanded spectacular views up and down the river and across to the settlement of New Amsterdam on the tip of Manhattan Island. A Dutch settler named Michael Pauw acquired lands along the west bank of the Hudson River in 1630, covering all of present-day Hoboken.1 In 1635, the lands passed to the Dutch West India Company, after which a period of conflict with the Native Americans left possession of the lands in constant dispute.2 A new indenture between the Native Americans and Petrus Stuyvesant of New Amsterdam secured title to the lands once and for all in 1658.3 Stuyvesant's tract of approximately 276 acres extended along the west bank of the Hudson River from Weehawken Cove to Hoboken Creek, a meandering tidal stream formally located near Newark Street. Governor Stuyvesant conveyed the tract to his brother-in-law, Nicholas Varlett, on February 5, 1663. This title was later confirmed by Philip Carteret on May 12, 1668. 5 One observer writing in 1680 described the tract a a good plantation in a neck of land almost on an island called Hobuck. It did belong to a Dutch merchant, Aert Teunissen, who formally, in the Indian war, had his wife, children and servants murdered by the Indians, and his house, cattle and stock destroyed by them. It is now settled again, and a mill erected there by one dwelling in New York. 6 Varlett died intestate in 1675. 7 Title passed to his daughter, Susanna de Freest, then to her daughter, Susanna Hickman, wife of Robert Hickman. The Hickmans sold the tract in 1711 to New York merchant Samuel Bayard. Bayard developed the property for farming and erected a comfortable summer residence on the promontory. So began a tradition of recreation and leisure that would continue with the property for 150 years. By 1760, according to the New York Mercury, Bayard's property included all the buildings needed for a well-managed farm and contained a five-acre garden with peaches, pears, plums, cherries, nectarines, and apricots, as well as sizable apple orchards of over a thousand trees. 8 The property also offered unparalleled convenience for marketing and commerce between the two shores. Cornelius Haring started regular ferry service from the southern tip of Hoboken to New York City in 1774. 9 The 1778 map of the area by John Hills illustrates the ferry landing and the original road leading north pg 4 through orchards and wooded groves along part of the present-day route of Washington Street. Bayard's loyalist grandson, William, had the land confiscated by the State of New Jersey in 1780. Abandoned, the house stood vacant until marauders torched it, and the fields went fallow for the remainder of the Revolution. At last in March 1784, the Bergen County agent of forfeited estates sold the Bayard tract to Colonel John Stevens, Jr. (1749-1838) for £18,360. Colonel John Stevens and the Creation of Hoboken Colonel John Stevens was a man of means and a great inventor, whose life and contributions to New Jersey's history are too numerous to recount here. Archibald Turnbull's 1928 biography of Stevens remains the seminal work on his life. Stevens began an immediate program of improvements to the former Bayard estate, but neglect had taken its toll.10 Ruined fields needed clearing. "I have near 200 boats of wood cut at Hobuck," he wrote shortly after acquiring the property, "and hope to have 3 or 400 more by winter." 11 He built a new country seat on the promontory, and by 1792 the Stevens family was spending the summer in the residence. The house was sufficiently grand and visible that some began to call it "Stevens' Castle" or "Castle Point." The name stuck. Large-scale improvements to Castle Point, including the planting of hundreds of new fruit trees and over 5,000 lombardy poplar trees, were well illustration: Stevens Castle, built and landscaped by Col. John Stevens (Winfield 1895). underway by 1797 to enhance the estate's salubrious air.12 The painter William Dunlap described the place as "built in the Style [sic] of English nobility," undoubtedly a reference to the fashionable, naturalistic British landscapes created by such masters as William Kent and Capability Brown.13 With an eye toward development, Stevens drew up a master plan in 1804 to create a new seaport town at Hoboken. The plan, prepared by Charles Loss and titled, "A Map of the new City of Hoboken," divided the lands south of Castle Point into house lots along a grid of streets aligned with the existing road to Weehawken (Washington Street). Stevens expended $50,000 "in making wharves, buildings, and other improvements at Hoboken" for the anticipated trade.14 The Hudson River's western bank, Stevens reasoned, offered a comparable location for the businesses of New York, but with a more healthful prospect, free from the city's squalor and disease. Outbreaks of cholera, typhoid, and yellow fever hindered New York commerce for long periods during the summer months, and prompted a flurry of efforts pg 5 designed to stem the spread. A yellow fever epidemic in 1803, for example, sent New Yorkers fleeing to the country.15 Stevens latched onto this seasonal turmoil to help promote his new town. In March 1804, he petitioned the New Jersey Legislature to establish the Hoboken Company, citing the concerns of sundry merchants, trades, manufacturers, and mechanicks [sic] who are at present inhabitants of the city of New York and of the other cities within the United States, together with many other persons who are necessarily dependent on them for their subsistence, are desirous of removing to a place where they may be able to pursue their respective vocations free from the danger of those epidemic disorders to which many of the Cities within the United States are at certain seasons subject, and where they will be exempt from the operation of certain laws and ordinances which they conceive to be impolitic and burdensome.16 Such development would have the added benefit of attracting business "highly advantageous to the State by the consequent increase of population, commerce and manufacturers...."17 The legislature failed to act, but Stevens pressed forward with his plans. He planned a sale of 800 lots to take place on March 20, 1804 at public venue over the course of four days and placed advertisements in the region's principal newspapers.18 The results were disappointing. Traversing the Hudson was less attractive and more expensive than migrating northward to Greenwich Village. Only low-cost transportation could help entice would-be settlers. Over the next two decades, Stevens devised various plans to improve communication between New York and Hoboken. These included plans for a tunnel, a floating bridge, and a permanent span.19 His experiments in steam propulsion for boats must also be considered within this context. In 1811, Stevens secured the lease on the franchise operating between Hoboken and New York and developed a steam-powered ferry service.20 Between 1817 and 1821, the family sublet the ferry franchise to others, but service proved so poor that Stevens sued to regain control. This also ignited his battle to overturn the New York state law granting Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston a monopoly on steamboat service across the Hudson. The case (Gibbons v. Ogden) landed in the United States Supreme Court, which struck down the New York franchise, arguing that only the federal government held the power to regulate interstate commerce. The ruling helped assert federal influence over the nation's economy. By 1825, some 43 steamboats competed to carry people and goods between New Jersey and New York.21 pg [6] illustration: A moonlit view of the north side of Castle Point from Elysian Fields, circa 1845 (Basil Stevens Scrapbook, New Jersey Historical Society). pg 7 ELYSIAN FIELDS New York's First "Central Park" Fast, regular, and reliable ferry service at last opened Hoboken to New York City. But instead of land, people came for recreation, and they came in droves. As early as the 1804 sale, to help entice settlers Stevens offered to make his private grounds around the estate available to purchasers as part of the deal.22 Visitors soon took advantage of the semi-public nature of Stevens' property, and by 1824 the ferries to and from Hoboken yielded, in Stevens' words, "an immense income, which is rapidly increasing as the population of the city and adjacent country increases." 23 He set about improving the grounds and a portion of the riverfront with a walkway to entertain the crowds. It was an instant hit. Over time the demand from New Yorkers to visit Stevens' shores grew so great, and his profits from the ferry service increased so much, that by 1824 he thought of turning over the entire shoreline to the City of New York: as a place of general resort for citizens, as well as strangers, for health and recreation. So easily accessible, and where in a few minutes the dust, noise, and bad smells of the city may be exchanged for the pure air, delightful shades and completely rural scenery, through walks extending along the margin of the majestic Hudson to an extent of more than a mile.24 His proposal also called for the erection of pavilions, "for affording every accommodation and refreshment, and also adequate protection against sudden showers of rain."25 For these structures he advocated the use of the best architectural styles, noting that perhaps nothing could have a more powerful tendency to civilize the general mass of society...in such promiscuous assemblages of the rich and poor, in situations where nature and art are made to contribute so largely to the embellishment of every scene presented to their view.26 But New York showed no interest in the envisioned park, so, undeterred, Stevens developed it himself. illustration top right: Wooded paths of Elysian Fields (Winfield 1895). pg 8 illustration top, Section of Douglass' (sic) Map - Localities in Hoboken: Elysian Fields occupied the north end of Hoboken in Douglas's Topographical Map of Jersey Cily, 1841 (Winfield 1895). At the ferry landing on the southern end of Hoboken, passengers emerged onto a wide lawn lined with elm trees. Stevens extended the waterfront path, now called the River Walk, around the base of Castle Point to the level ground at the property's north end. Here he created a clearing in the tree-lined shore called "Turtle Cove" where by 1824, hungry picnickers sated themselves on bowls of turtle soup.27 In 1826, a visiting traveler on a tour through North America noted, "the beautiful walk extending for two miles along the Hudson is kept in the finest order, and commands a noble view of the city on the opposite shore."28 The Scotsman James Stuart, who spent the Winter of 1829 and 1830 residing in Hoboken, praised the Stevens' for their accomplishments: "They have laid out their property adjoining the river, for about two miles, in public walks, which the inhabitants of New York, who come over in prodigious numbers, enjoy very much."29 Stuart went on to note the corresponding increase in the value of the ferry, as well as the rent on Stevens-owned businesses such as the hotel.30 Improvements to the park continued into the 1830s. Among the shelters and watering places Stevens constructed were a grotto-like cave at the base of Castle Point called Sybil's Cave and a large Grecian temple at Turtle Cove. On May 21, 1831, diarist Philip Hone wrote: "Messrs. Stevens have a large number of men employed in laying out the grounds in a very tasteful manner, and erecting a large, light airy building, which is to be called by the classic name of Tivoli, near the place formally known as Turtle Grove, at the extremity of the beautiful walk from the ferry."31 Called "The Colonnade," the structure stood east of present-day Hudson illustration center, Turtle Club season ticket: The club met at Turtle Cove (Winfield 1895). pg 9 Street, between Eleventh and Twelfth Streets on the former Maxwell House Coffee Plant site. "It will be thronged every sultry afternoon through the summer," wrote an enthusiastic reporter in the Intrepeiad newspaper, "if it is kept up in the spirit of its commencement."32 In keeping with the classical nature of The Colonnade, Stevens renamed the area "Elysian Fields" after the heavenly abode of the dead in ancient Greek mythology, and he opened it in a grand public celebration on July 11, 1831.33 Elysian Fields, vast in its expanse with open ground, wooded groves, and meadows, extended from the northern base of Castle Point to the deepest reach of Weehawken Cove, and provided welcome space for an assortment of uses. Picnics, sports, and games allowed the New York multitudes to stretch their legs in relative freedom.34 Theodore Sedgewick Fay wrote in 1831 that a newcomer to Elysian Fields could react "with delight and upon the softness, the brightness and variety of this scene, the improvements of which... are laid out in great taste.35 Frances Trollope, a visiting Englishwoman pronounced it a "little Eden" and said it was hardly possible to imagine one of greater attraction.... [H]e has restricted his pleasure grounds to a few beautiful acres, laying out the remainder simply and tastefully as a public walk....a broad belt of light underwood and flower shrubs, studded at intervals with loft forest trees, runs for two miles along a cliff which overhangs the matchless Hudson: sometimes it feathers the rocks down to its very margin, and at others leaves a pebbly shore, just rude enough to break the gentle waves, and make a music which mimics softly the loud chorus of the ocean.36 By 1832, Samuel Lorenzo Knapp estimated that as many as 20,000 visitors a day descended on Hoboken during the summer season to find "a most delightful retreat for a summer's day."37 For all intents and purposes, Stevens and his family had effectively created New York's first "Central Park."38 illustration left: A. Dick's 1831 view of The Colonnade at Elysian Fields, looking south (Winfield 1895). Marketing Elysian Fields Hoboken's success rested in part on America's growing interest in its natural surroundings. Beginning in the 1820s and 1830s, architects and tastemakers such as Asher Benjamin, Alexander Jackson Davis, and Andrew Jackson Downing advocated the pg 10 illustration top: New York Evening Post advertisement for Elysian Fields, June 2, 1846. virtues of country living in their landscape plans, building designs, and popular treatises.39 The origins of this movement, and the relationship between nature, Classical and Medieval-style architecture, and Christian virtue, had its roots in England but found fertile ground in the Hudson River Valley, where landscape painters of the period exulted in the raw, untamed qualities of the American wilderness. Many of New York's artistic and literary circle visited Stevens' park to find their own form of inspiration. Asher B. Durand, Robert Weir, William James Bennett, Jasper Francis Cropsey, Robert Havell, Charles Loring Elliot, and William Tylee Ranney were among the painters to visit and sketch in Elysian Fields.40 Durand spent most Sunday's there, "strolling under the noble trees of the Elysian Fields."41 In 1830, William Cullen Bryant extolled the beauty of the wooded walks, particularly in May, "when the verdure of the turf is as bright as the green of the rainbow; and when the embowering shrubs are in flower."42 Robert Sands described the Elysian Fields in 1832 as "one of the prettiest places you may see of a summer's day," with wooded groves " worthy of being painted by Claude Lorraine [sic]."43 As late as 1844, Lydia Maria Child described moonlit nights in Hoboken "beautiful beyond illustration bottom: View of New York City and Castle Point from Elysian Fields (Basil Stevens Scrapbook, New Jersey Historical Society). pg 11 imagining" and Elysian Fields as a place "where a poet's disembodied spirit might well be content to wander."44 This picturesque setting was by one account among the earliest public or semi-public landscaped gardens in America 45 To keep visitors coming, the Stevens' relied on three things: quality transportation, changing attractions, and advertising. Comfortable appointments on fast, reliable boats made the river crossing both pleasurable and affordable. Every few years, Stevens embellished the park with improvements or new attractions, and he rented out areas for various private affairs or public spectacles. Newspaper advertisements trumpeted Hoboken as the best "of all rural excursions that can be made from the city" and appeared regularly for years in one form or another in the city's press.46 Fledgling city directories, such as Gavit's Directory, proclaimed places like the village of Hoboken, "with its Elysian Fields, Sybil's Cave, serpentine walk, and shady retreats...the 'great park' and picnic ground for pleasure seekers from the great city on the other side of the river...."47 Other special amusements included a merry-go-round, a tenpin alley, and wax figures.48 A crude ferris wheel-like contraption near The Colonnade gave thrill-seekers a chance to take in the scenery from changing elevations. The Stevens' supplemented these attractions with staged entertainments such as horseraces, ox roasts, and Indian war dances.49 Rented tents, carnival booths, and tables and benches provided opportunities to watch the human parade in relative comfort.50 As a venue available for rent, Elysian Fields also enjoyed free advertising from all those who hired the facilities. P. T. Barnum's 1843 announcement in the New York press of his "Grand Buffalo Hunt, Free of Charge" brought 24,000 spectators to the Trotting Course at Hoboken, where the animals ultimately broke the fence and sent the crowd running.51 Boating Pleasure boating, yet another form of leisure, also took root in Elysian Fields. John Cox Stevens, an outgoing, energetic member of the Stevens clan, helped popularize yachting more than any other. In July 1844, Stevens gathered together a group of like-minded yachtsmen for a sail to Newport. This "saucy-looking squadron of schooner-yachts lying off the Battery ... excites considerable admiration," wrote one New York diarist on July 29. 52 The next day, Stevens summoned members of the party to his vessel Gimcrack and proposed they form a boat club.53 illustration right: First New York Yacht Club clubhouse (Basil Stevens Scrapbook. New Jersey Historical Society). pg 12 Organized under the name of the NYYC, the group elected Stevens as their first Commodore. Later that year, Stevens commissioned their first permanent clubhouse on family lands at Elysian Fields, and on July 15, 1845, the club met for the first time in their new quarters near the foot of present-day Tenth Street.54 While the architect for the tiny Gothic-Style cottage is unknown, the popular romantic designer Alexander Jackson Davis, then engaged in designing Stevens' New York townhouse at College Place and Murray Street, may well have authored the building.55 Davis favored historical models, drawing from classical antiquity and the English gothic for inspiration. John Cox Stevens maintained a long and fruitful professional relationship with Davis long after the clubhouse was built, adding credence to the attribution.56 Two days after their first meeting in Hoboken, the club members sailed their first "trial of speed." The course ran from Robbins Reef to Bay Ridge and Stapleton, through the Narrows to a point off Southwest Spit, and back to the finish off of the clubhouse at Elysian Fields.57 The "race" attracted thousands who watched from both shores and chartered steamers.58 Commodore Stevens placed third on board Gimcrack. From that time forward, the club began and ended its annual regatta off the clubhouse grounds at Elysian Fields until 1865. The club's most famous race, however, began overseas. While based in Hoboken, John Cox Stevens built the yacht America, and in 1851 sailed it to England to race and win the first "America's Cup" against 14 British yachts on a course around the Isle of Wight.59 Stevens and the NYYC were henceforth forever tied to the yachting world's best known contest, although the actual cup stayed safely tucked away in the winner's private residence, not the clubhouse. By 1868, the original clubhouse had outlived its usefulness, and the membership voted to relocate to Staten Island.60 The smaller New Jersey Yacht Club, organized originally in 1871, took over the Hoboken clubhouse and remained there from 1875 to 1898.61 After acquiring the site in 1899, the Pennsylvania Railroad presented the original structure to the NYYC.62 In 1904, the club floated the building by barge from Elysian Fields to Glen Cove, Long Island, where it served as a station stop.63 Later it was moved to the Mystic Seaport Museum, then to the grounds of the NYYC's Newport, Rhode Island clubhouse, where it remains to this day. Baseball Among the many sports played at Elysian Fields, pleasure seekers favored games with balls and bats from an early date. Fresh air and wide spaces offered clubs the ideal place to meet and play, away from the rapidly diminishing open lots of New York. Most historians agree that these matches resembled the English games of rounders and cricket 64 As early as October 21, 1845, according to the New York Herald, teams of nine New Yorkers faced off with nine Brooklynites to play at Elysian Fields under the new rules devised by Alexander Cartwright.65 The New York team, called the Knickerbocker Ball Club, went on pg 13 illustration top: A match with the Hoboken Cricket Club attracted crowds in 1856 (Basil Stevens Scrapbook, New Jersey Historical Society) to compete in the more well known match against the New York Base Ball Club on June 19, 1846, where the New York team won 23 to 1. 66 Also played at Elysian Fields, this game is most often cited as the beginning of modern baseball. Subsequent games, both formal and informal, continued at the park. Many won special notoriety. The Knickerbockers played The Washington Club of Yorkville in 1851, winning 21 to 11. 67 A match between the Eagles and the Gothams at Elysian Fields on September 8, 1857 was illustrated for a local magazine. On October 21, 1861, some 15,000 observers watched all-star teams from New York and Brooklyn compete for a silver baseball trophy.68 Another championship match between the Mutual Club of Manhattan and the Atlantic Club of Brooklyn on August 3, 1865, attracted 20,000 spectators to Elysian Fields and became the subject of a popular lithograph produced by Currier and Ives in 1866. By mid-century, Hoboken served as one of the game's most popular venues.69 The exact location of the first game, or later ones for that matter, is anyone's guess. The Douglass map of 1841 shows at least three clearings on the north side of Castle Point. One lay on the high ground behind Stevens Castle, between Tenth, Eleventh, Hudson, and Washington Streets. This was known as the St. George Cricket Ground.70 Two others to the north of The Colonnade were for other sports as well. Many of the known ball clubs favored the northern fields, and in 1865, with permission from the Stevens illustration right: Currier & Ives print, The American Game of Baseball (Crouse 1930) pg 14 family, three teams set about "enlarging and improving the grounds, cutting down several trees, removing rocks, leveling and turfing, as well as erecting several rows of seats for spectators."71 The newly improved northern fields opened on May 25, 1865.72 Bachman's 1866 Bird's Eye View of New York City and Environs illustrates the back side of The Colonnade, and its surrounding grounds with a game of baseball underway in the northern clearing. Another field lay south of The Colonnade. Its approximate location was at the intersection of Hudson and Eleventh Streets. William A. Shephard recalled his visits to what seems to be the southern field in the late 1850s: A walk of about a mile and a half from the ferry, up the Jersey shore of the Hudson River, along a road that skirted the river bank on one side and was hugged by trees and thicket on the other, brought one suddenly to an opening in the "forest Primeval." This open spot was a level, grass-covered plain, some two hundred yards across, and as deep, surrounded upon three sides by the typical eastern undergrowth and woods and on the east by the Hudson River. It was a perfect greensward [turf].73 In 1946, the City of Hoboken installed a plaque at the foot of Eleventh Street to commemorate what they believed to be the site of the historic 1846 game. Their choice of location was based in part on the personal recollections of someone who played on the field, although the man had been born in 1864, long after the event.74 Baseball's great popularity, and the unpoliced character of Elysian Fields, brought with it drawbacks. Crowds took a heavy toll on the ferry boats, grounds, and facilities.75 A brawl, well remembered for, years to come, erupted among members of a German social club at Elysian Fields in 1851.76 In 1865, one ball match between the Mutuals and the Eckfords attracted so much betting and included so many unusual plays that team-members were accused of throwing the illustration bottom: Baseball game underway in lower left, next to The Colonnade (Bird's Eye View of New York City 1866. New York P... [truncated due to length]

![pg [i] title](https://i0.wp.com/d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/dcf5d420-fa71-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdZus9.tn.jpg?w=604&ssl=1)

![pg [ii] credits and acknowledgements](https://i0.wp.com/d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/de2860b0-fa71-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFd0wvo.tn.jpg?w=604&ssl=1)

![pg [iii] Contents](https://i0.wp.com/d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/df58f170-fa71-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFd0wwj.tn.jpg?w=604&ssl=1)

![pg [iv] Aerial photo of Maxwell House Coffee plant, April 1940](https://i0.wp.com/d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/e089f760-fa71-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFd0w3r.tn.jpg?w=604&ssl=1)

![pg [2]](https://i0.wp.com/d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/e2ec9f80-fa71-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFd0xas.tn.jpg?w=604&ssl=1)

![pg [6] illustration: The Elysian Fields & Castle Point, circa 1845](https://i0.wp.com/d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/e7b1c8b0-fa71-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFd0zfC.tn.jpg?w=604&ssl=1)

![pg [16]](https://i0.wp.com/d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/f39f3860-fa71-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFd0Eky.tn.jpg?w=604&ssl=1)

![pg [22] photo of stacked sacks of green coffee beans, 1941](https://i0.wp.com/d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/fac730c0-fa71-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFd0Ivh.tn.jpg?w=604&ssl=1)

![pg [32] color aerial photo of plant, ca. 1990](https://i0.wp.com/d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/06b58ad0-fa72-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFd0NOh.tn.jpg?w=604&ssl=1)