Naval Warfare

Naval Warfare

The pioneering work of Robert and Edwin Stevens in warship engineering was not as successful as the railroad, but it likely influenced advances in naval warfare in the mid nineteenth century. The Stevens Battery, an ironclad warship that was planned but never completed, demonstrated and likely inspired advances in warship construction.

The battery had a long history. During the War of 1812, Colonel John Stevens wrote a proposal for a circular iron-plated battery that would be anchored in a harbor. The battery would spin under the power of steam propellers and fire successive guns at the enemy. The battery and other ironclads John Stevens later proposed were not pursued by the Navy. In 1824, Robert Stevens wrote to the Navy advocating that they purchase long steel shells that he designed, as well as support the construction of a mobile “steam battery.” He cited the threats of European expansion and despotism, and noted that America’s military was weak compared to England and France.

The battery had a long history. During the War of 1812, Colonel John Stevens wrote a proposal for a circular iron-plated battery that would be anchored in a harbor. The battery would spin under the power of steam propellers and fire successive guns at the enemy. The battery and other ironclads John Stevens later proposed were not pursued by the Navy. In 1824, Robert Stevens wrote to the Navy advocating that they purchase long steel shells that he designed, as well as support the construction of a mobile “steam battery.” He cited the threats of European expansion and despotism, and noted that America’s military was weak compared to England and France.

In the 1840s, Congress began to show interest in the kind of warship construction that the Stevens family had advocated. In 1841 Congress sent a board of army and navy officers to observe Edwin’s experiments with iron armor. The layered iron plates that he had riveted together resisted shots from the most powerful guns in common use at the time. The next year, Congress passed the “Act Authorizing the Construction of a Steamer for Harbor Defense.” Robert Stevens was contracted to build an ironclad. The proposed design was changed multiple times over many years as construction was unable to keep pace with advances in naval armament. When Robert Stevens died in 1856, only the hull was completed and the project was already far over budget.

The outbreak of the Civil War and Confederate experiments with ironclad warships led to more agitation to complete the Stevens Battery. An article in Scientific American noted that luxurious passenger steamers had cost more money than had been spent on the Battery. Edwin Stevens lobbied for its completion. Funding was appropriated, but in July 1862 the Secretary of the Navy vetoed the funding and the battery was given to heirs of Robert Stevens. By 1863 other ironclads had been built and the Navy did not think the Stevens Battery could fill any need they had.

In 1868 Edwin died and he willed the Battery to the State of New Jersey along with a million dollars to complete it. The money was not spent effectively and the hull was finally scrapped in 1881.

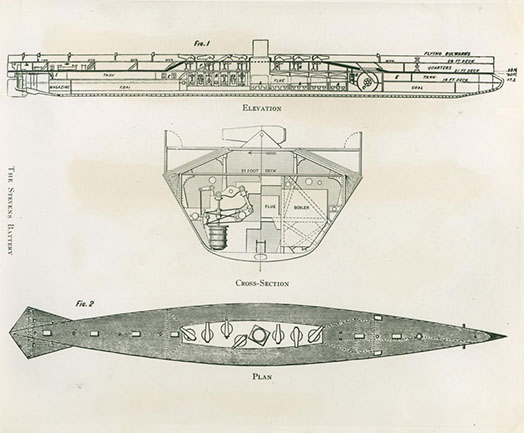

The design and purpose of the Battery changed over time. Robert originally intended it to be a mobile gun battery for the defense of New York harbor. Later it was changed to be an ocean-going cruiser. The iron hull was 420 feet long, 53 feet wide, and 23.5 ft deep. Plans called for ballast tanks so that much of the hull could be submerged during battle. The use of screws instead of paddlewheels meant that the entire propulsion system would be underwater. The ship would be outfitted with turreted guns that could be trained in any direction.

If completed, the Battery would have been faster than other ironclads and effectively armed. However, it had little use in the Civil War, as it had too deep a draught to navigate shallow Southern waterways and had limited range and survivability on the open ocean. The experiments and designs of the Stevens brothers likely influenced French warship designers who put slow steaming ironclads to use during the Crimean War in 1854. The Stevens Battery, though it was not successful, did inspire later innovation.

Sources

J. Elfreth Watkins, “John Stevens and His Sons,” 10-11. Stevens Family Collection.

Jim Hans, 100 Hoboken Firsts. 21-22

Michael Orth, “The Stevens Battery,” Stevens Indicator, 1967. Stevens Family Collection.

Robert Stevens Letters, Stevens Family Collection.