The Family

The grandfather of Hoboken’s founder, also named John Stevens, emigrated from England to New York City in 1699 at the age of seventeen. He served a seven year indenture as a clerk to a crown official in New York, then pursued interests in land and mining. He came to the Jerseys after hearing about copper mining in Rocky Hill, near Princeton. He soon found the business of land to be more profitable (though he would eventually acquire the Rocky Hill mines). While living in the Princeton area he met Ann Campbell, whose father owned land as a shareholder and proxy for New Jersey’s Proprietors. John and Ann married in 1714, and John Stevens now joined in Ann’s father’s land business. They left many scattered tracts of land in New Jersey to their children when John died in 1737.

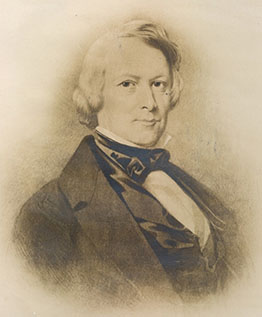

The father of Hoboken’s founder, the Honorable John Stevens (1716 – 1792) was a prominent merchant. He served on the New Jersey Royal Governor’s council until he resigned to support the cause of Independence. He was also a slaveholder, at least for part of his life. His wife, Mary Alexander, was a daughter of the surveyor-general of New York and New Jersey. He had two children, John in 1749, and Mary in 1752. The Honorable John Stevens would serve in the New Jersey legislature after Independence as well.

⚡ Stevens Family: Fast Facts

- The Founder: Colonel John Stevens (1749–1838) founded Hoboken and was a leading advocate for the first U.S. patent laws.

- Transportation Firsts:

- Designed the first American-built steam locomotive.

- Operated the Phoenix, the first steamboat to successfully navigate the open ocean.

- The “T-Rail”: Robert L. Stevens invented the T-rail, the inverted “T” shape for tracks that became the global standard for railroads.

- The America’s Cup: John Cox Stevens founded the New York Yacht Club and led the syndicate that won the very first America’s Cup in 1851.

- Educational Legacy: Edwin A. Stevens bequeathed the land and funds to establish the Stevens Institute of Technology, the first U.S. college dedicated to mechanical engineering.

- Philanthropy: Martha Bayard Stevens was a prolific philanthropist, funding the construction of the Church of the Holy Innocents and numerous civic projects in Hoboken.

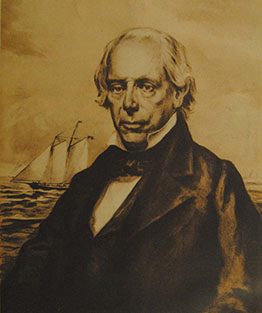

John Stevens (1749-1838), often referred to as Colonel John Stevens, was Hoboken’s founder, a patriot, attorney, and civic-minded inventor. He was a pioneer, even a visionary, in steam powered transportation on sea and land. Charles King, president of Columbia University, wrote of him in 1852: “Born to affluence, his whole life was devoted to experiments, at his own cost, for the common good… Time has vindicated his claim to the character of a far-seeing, accurate, and skillful, practical experimentalist and inventor… The thinker was ahead of his age.”

John was born in New York City in 1749, but spent most of his childhood at the family home in Amboy. In 1760, the family established a winter home in Manhattan. John graduated King’s College (now Columbia) in 1768, then studied law and became an attorney in New York in 1771.

Young John and his sister forged close relationships with the powerful Livingston family. In 1771 Mary Stevens and Robert Livingston Jr. were married. The Livingstons had significant influence in New York politics in the colonial and early republican eras. Their influence would not benefit the Stevens family when John Stevens and Robert Livingston were on opposite sides of a steamboat navigation dispute in the 1800s.

Like his father, young John Stevens joined the Patriot cause and offered his services. On July 15, 1776, he was appointed Treasurer of New Jersey. Successfully carrying out his duties in war-torn New Jersey required him to navigate the state on horseback evading British and Tory troops as he raised funds and paid bills for the state. His service earned him the rank of colonel.

Rachel Cox, a beautiful daughter of Colonel John Cox, caught John’s fancy and the two of them married in October 1782. After hostilities with Britain ceased, they moved to the Stevens home in Manhattan and planned to acquire land and raise a family. John looked across the river to the future.

Colonel John Stevens and his wife Rachel would have 13 children. Their most well-known sons are John Cox Stevens (1785-1857), Robert Livingston Stevens (1787-1856), and Edwin Augustus Stevens (1795-1868).

| John Cox Stevens | Robert Livingston Stevens | Edwin Augustus Stevens | |

| Primary Focus | Maritime & Sport | Engineering & Rail | Business & Education |

| Key Invention | Organized Yachting | The T-Rail (Standard Track) | The “Stevens Battery” (Ironclad) |

| Famous First | Won the first America’s Cup | Built the first steam locomotive in the U.S. | Founded America’s 1st mechanical engineering college |

| Organization | New York Yacht Club | Camden & Amboy Railroad | Stevens Institute of Technology |

| Defining Trait | The Visionary Diplomat | The Inventive Genius | The Strategic Philanthropist |

John Cox Stevens represented the family in business when needed and enjoyed sailing as often as he could. As a founder of the New York Yacht Club, he sailed the America to victory in the race that would become the America’s Cup.

Robert’s creative imagination was noticed at an early age and as a youth he was given tools and mathematical training. Robert made an incredible number of advances in the construction of railroads and ships. He had attended Columbia like his father, but left before graduating to learn about mechanical operations in Hoboken machine shops.

Edwin had a mind for engineering and business, and he often worked with his brother Robert on joint ventures. Edwin firmly anchored the Stevens legacy in Hoboken by founding the Stevens Institute, America’s first college devoted to mechanical engineering.

There were proud civic leaders among the women in the Stevens family.

Martha Bayard Stevens, wife of Edwin Augustus, was known for her philanthropic contributions to Hoboken.

Caroline Bayard Stevens was so well regarded for her civic work that her death was mourned at the White House.

Millicent Fenwick, a great-granddaughter of Edwin, was a respected member of the United States Congress.

In 1897, Abram S. Hewitt fondly recalled the Stevens family in an address at the Stevens Institute. Hewitt had been a mayor of New York City, a member of Congress, and a leader in the ironworks business. Yet when he first visited the elderly John Stevens at Castle Point, he was a curious young boy, the son of a mechanic who had developed a friendly relation with John while working on his steam engines. Hewitt was impressed by the genuine enthusiasm and friendliness shown by the man in his eighties who was still possessed of an active and alert mind.

“I was welcomed to Castle Point in my early youth just as I would be today by the honored mistress of that mansion. They did not believe that the acquisition of wealth was sufficient for the development of human nature… The sense for beauty was manifest in all that they did.”

Sources

Archibald Douglas Turnbull. John Stevens, an American Record. Archive.org.

Charles King, Preface to Stevens, “Documents Tending to prove the Superior Advantages of Rail-ways and Steam Carriages Over Canal Navigation.” iii-vi. Archive.org.

George Iles. Leading American Inventors. Family History, 5-6; Hewitt praising the Stevens family, 35, 37-38. Archive.org.

Leading Innovation: A Brief History of Stevens, Stevens Institute of Technology. www.stevens.edu

J. Elfreth Watkins, “John Stevens and His Sons,” 3,6. Stevens Family Collection.

Mary Stevens Baird Recollections, Stevens Family Collection. V, 3.