Collections Item Detail

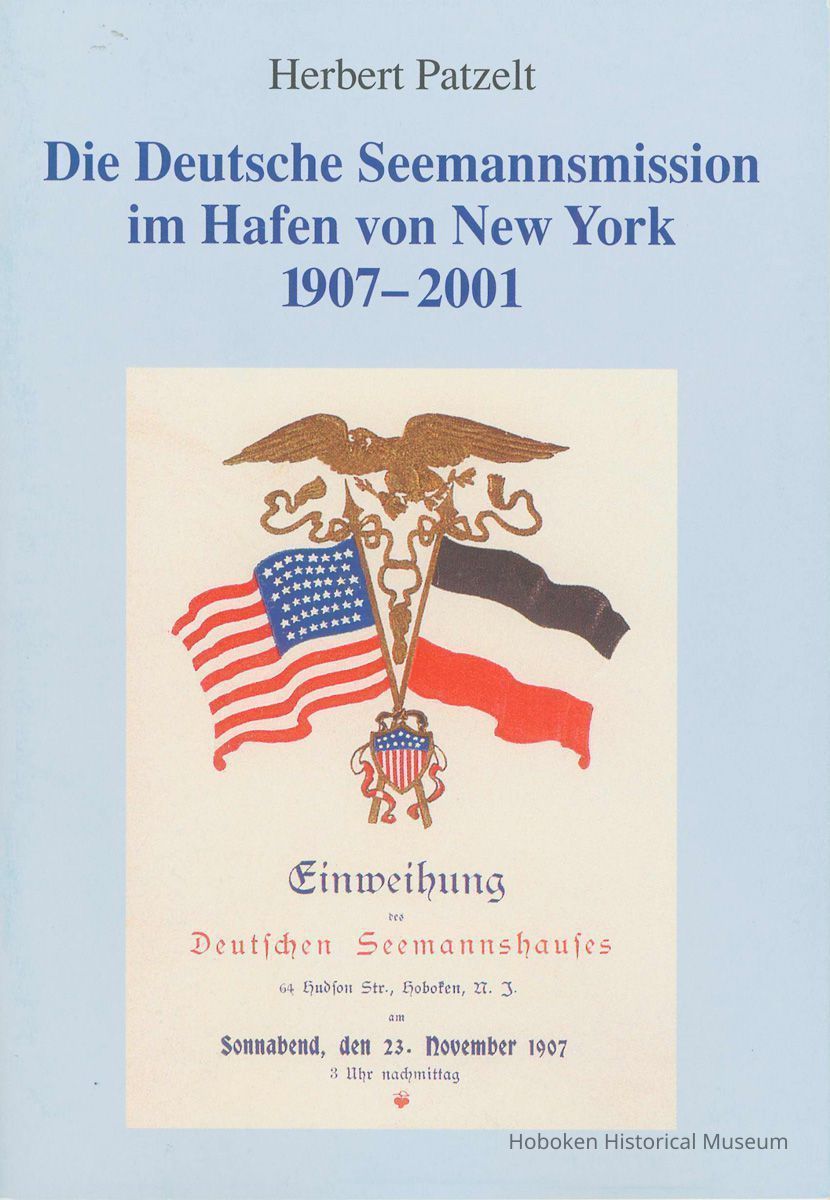

Die Deutsche Seemannsmission im Hafen von New York 1907-2001. (The German Seaman's Mission in the Port of New York. By Herbert Patzelt, Munich, 2002.)

2003.015.0001

2003.015

Patzelt, Dr. Herbert

Gift

Gift of Dr. Herbert Patzelt.

1907 - 2002

Date(s) Created: 2002 Date(s): 1907-2002 Level of Description: Folder

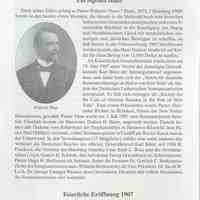

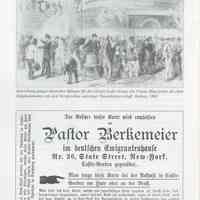

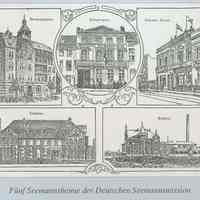

Display Value: Good Notes: 2003.015.0001 Cataloguer's note: The translator's four notes are below. They are on the two paper copies of the translation and explain the text summary and formatting. Users are referred to them because the text in this record is not formatted, i.e. no italics. Also the photo and illustration captions are not translated. Also the George B. Steil in text may actually be George H. Steil, Mayor of Hoboken, 1906-1910. 1. Translator's note: This English version of Die Deutsche Seemannsmission im Hafen von New York 1907-2001 by Herbert Patzelt (Munich, n.d.) was prepared for the Hoboken Historical Museum by Beth Jackson Berman. 2. Translator's note: Throughout this document, italicized text represents a summary, rather than a translation, of the original. 3. Translator's note: Only the literal sense of Brückner's poem has been translated; no attempt has been made to preserve its poetic qualities. This applies equally to the other poems by Brückner in this document. 4. Translator's note: Pastor Brückner took his own life. Author Patzelt cites in a footnote a letter dated March 13, 1957 that he received from Director Johannes Wolff of St. Stephan's in Hannover: "In the face of such an event, we will not pass judgment, but think instead of what the Apostle John wrote in his first letter, Chapter 3, Verses 19-21." THE GERMAN SEAMEN'S MISSION IN THE PORT OF NEW YORK 1907 - 2001 By Herbert Patzelt [Cover illustration:] Dedication of the German Seamen's Home 64 Hudson Street, Hoboken, N.J. Saturday, November 23, 1907 3:00 p.m. Introduction It was while a theology student at Tübingen that I decided to go to America to study. In the summer of 1952, I arrived in Fremont, Nebraska, roughly in the middle of the North American continent, where my cousin Dr. Richard Syre was Professor of the Old and New Testaments at Central Lutheran Theological Seminary. There I received my Bachelor of Divinity (B.D.) degree in May 1953. I then went to Germantown, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia, to attend the Lutheran Theological Seminary, where I earned the degree of Master of Sacred Theology (S.T.M.) with a thesis on Luther's teachings on law. At the time, in the wake of the enormous injustices of the Second World War, many of us were seeking a basis for jurisprudence in natural law, and thus looked to the works of Martin Luther and John Calvin, for example, to see if some theological doctrine of law could be derived from their writings. My impressions of America dazzled me. The size of the country, the modernity of life, the many and stimulating professional opportunities that existed there sparked my enthusiasm and helped to shape me as a pastor. Then, unexpectedly, I was asked by Pastor Heinrich Arend Kropp (1892-1956) to take over the German Seamen's Mission in the Port of New York. I agreed, and began work on March 1, 1954. So that I could be properly ordained and appointed, the directors of the hitherto independent Seamen's Mission applied for and were granted membership in the New York and New England Synod of the Lutheran Church. I was ordained on June 17, 1954, in Johnson City, New York, by Frederick R. Knubel, President of the United Synod of New York and New England. This unexpected turn of events in my life, along with my official pastoral duties in the huge metropolis, led me to develop an interest in history. Brief History of Seamen's Missions The first seamen's missions were started by an Englishman, Charles G. Smith (1781-1862), who had spent six years in the British navy. Smith's network of missions offered refuge and protection to English-speaking sailors in all major ports. In the United States, organized seamen's welfare work began in 1818; in 1820, a church was opened by the "Society for Promoting the Gospel among Seamen in the Port of New York." By the time the German Seamen's Home opened in Hoboken in 1907, the Port of New York had 13 seamen's welfare societies with five churches, 17 reading rooms, 11 pastors and 18 missionaries or deacons. German Seamen's Missions The first institutions devoted to the welfare of German seamen were established in the 1870s, the earliest being located in Great Britain and St. Petersburg, Russia. In 1885, the "General Committee for German Evangelical Seamen's Missions" was formed in Germany, and Lutheran societies in various ports began to implement the Committee's work. A directory published by the General Committee in 1909 listed 175 ports served by German seamen's missions. According to the 1909 directory, there were 29 seamen's homes (with living accommodations) at the time, with 44 reading rooms, 20 pastors, 40 housemasters and deacons, and about 90 part-time employees. In the Port of New York In the United States, organizations to assist Lutheran immigrants had been established in Philadelphia and New York in the 1860s. In 1873, the German Lutheran Emigrants House opened at 26 State Street in lower Manhattan, near Battery Park and convenient to Castle Garden. The Emigrants House served German immigrants and seafarers alike. In 1905, Dr. Gottlieb C. Berkemeier, son of the Emigrants House director, became interested in seamen's welfare in particular. With the help of Pastor Dr. George Unangst Wenner of New York, Dr. Berkemeier persuaded a Lutheran organization in Hannover to send a representative to found a seamen's mission in the Port of New York. Pastor Wilhelm Thun (1872-1969) arrived with this assignment in September 1906. Early meetings of the German Seamen's Mission in the Port of New York were held at the Imperial German General Consulate (11 Broadway) and at the Lutheran Emigrants House in lower Manhattan. The practical work of the Mission began in Hoboken, N.J., a municipality directly across from New York City referred to jokingly at the turn of the century as a "suburb of Bremen." In his first two months on the job, the energetic and enthusiastic Pastor Thun not only established contacts with the local Lutheran congregations, most of which were still exclusively German, but also managed to secure financial backing for the German Seamen's Mission in the form of large lump-sum and annual contributions from Hamburg-American (Hapag) and North German Lloyd. At its February 1907 meeting, the fledgling Seamen's Mission voted to buy the building at 64 Hudson Street in Hoboken, on credit, for a sum of $12,000. What was known officially as the "Society for the Care of German Seamen in the Port of New York" was formally established as a post of the German Lutheran Seamen's Mission on June 19, 1907. On that date, at a meeting held at the Imperial German General Consulate in New York, the Society's by-laws were approved; in addition, the German General Consul, Karl Bünz, was named the Society's first chairman. Pastor Alexander Richter, head of the Lutheran pastorate in New York, was selected to be the first president of the German Seamen's Mission in Hoboken. On July 1, 1907, Pastor Thun was formally appointed to the position of Seamen's Chaplain, and a Housemaster, Deacon H. Haars, was hired. (Haars, like all deacons at the Seamen's Home in this period, came from the Brethren's Home of St. Stephan in Hannover, directed by Pastor Paul Oehlkers, formerly Seamen's Chaplain in Cardiff and on the Lower Weser.) The original 15-member board of directors of the new Seamen's Mission included a representative of the German Empire (ex officio), General Consul Karl Bünz (succeeded in 1908 by R. Franksen); a representative of the Hamburg-America Line, Emil L. Boas; and a representative of North German Lloyd, Gustav H. Schwab. Attorney George Gravenhorst was the treasurer, and Pastor Hugo W. Hoffmann the secretary. The vice-president was Dr. Gottlieb C. Berkemeier. Dr. Jacob W. Loch and Dr. George Unangst Wenner, to whose dedication and wisdom the Seamen's Mission was much indebted, were also named to the first board. Opening Ceremony 1907 The Seamen's Home at 64 Hudson Street was dedicated on November 23, 1907. Members of the Society for the Care of German Seamen attended the ceremony, as did officials from the German Consulate and state and local authorities. Also present were representatives of the shipping companies and business community; members of allied missions in New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore; pastors and congregants of various Lutheran churches; and delegates from ships anchored in the harbor. After welcoming remarks by President Alexander Richter, the Seamen's Home was dedicated by Pastor Thun, who took as his text Genesis 12:2, "I will bless you and make your name great, and you shall be a blessing." Other speakers that day included Deputy General Consul C. Gneist of the Imperial German General Consulate; Gustav H. Schwab of North German Lloyd; and the Honorable George B.[sic - H.] Steil, Mayor of the City of Hoboken. Finally, Vice-President Berkemeier reminded those assembled of the tasks that lay ahead, such as providing overnight accommodations for sailors and establishing auxiliary posts near Bushwick and elsewhere in the New York metropolitan area. Early Days In December 1907, a second Seamen's Chaplain was appointed to assist the successful and extremely busy Pastor Thun. The newcomer was Pastor Franz Trentepohl of Atens (Oldenburg). The extent of the Mission's work at this point is reflected by its reported statistics. From January 21 to April 26, 1908, the Seamen's Home in Hoboken was visited by 7575 seamen. In the same period, 824 seamen attended religious services, while 279 received sick visits. There were 121 visits to ships. Two devotional services were conducted weekly, and at Eastertime two shipboard services were held. The Easter service for the men of the two North German Lloyd steamers docked in Hoboken took place on the Kronprinzen, while that for the crews of the three Hapag steamers was held on the Auguste Victoria. Each of these Easter services was attended by over 300 men. As it happened, the many responsibilities and demands of work at the Seamen's Mission soon proved too strenuous for Pastor Trentepohl. Since Wilhelm Thun was scheduled to begin a new assignment in Germany as soon as possible, the Mission's board of directors instructed him to return to his homeland to seek his own successor. In Germany, Thun learned from Gustav Adolf Wendelin, a religious leader in Dresden, of a clergyman named Hermann Brückner, then an assistant at the Court and Garrison Church of St. Jacob in Weimar. On August 17, 1908, Hermann Brückner met in Bingen am Rhein with two members of the board of directors from Hoboken, Drs. Loch and Hoffmann. It was clear that the right man had been found. Brückner arrived in Hoboken in November 1908 and, along with a new Housemaster, Deacon A. Lammert of St. Stephan's, officially began work in March 1909. Pastor Thun, seeing that the Seamen's Mission in the Port of New York had established firm roots during his two years of work, turned responsibility for its future over to Pastor Brückner, who, after five months of training, performed his duties as Seamen's Chaplain with the greatest devotion for the next forty-five years. The board of directors was highly appreciative of Pastor Thun's work, praising his energy, devotion and achievements. In a letter to the German Lutheran Welfare Society in Hamburg, President Richter spoke glowingly of Thun's gifts. A farewell dinner was held on March 15, 1909, for Pastor Thun, who returned to Germany soon afterward. Hermann Brückner, Son of Weimar Hermann Brückner was born in Eisenach on May 12, 1883. His father, Otto Brückner, was the Grand-Ducal Surveyor in Weimar, while his mother, Wilhelmine Ernestine Ziegler, came from Biberach in Württemberg. Brückner grew up in Weimar at a time when a whiff of the classical era remained in the air. Born into an old Weimar family, he felt close ties to that city and its unique genius loci all his life. It was in Weimar that Brückner's spirit, as ardent and lively as it was refined and genteel, was truly at home. During his theological studies in Leipzig, Greifswald and Jena, Brückner, out of personal interest, had done extensive work in French and English language and literature. His knowledge and skills made him seem especially suited for a foreign post. He was ordained in Weimar on October 14, 1906, and began work at the Court and Garrison Church of St. Jacob in Weimar in 1907.* Hermann Brückner was one of those people who throw themselves entirely into whatever they undertake. In Hoboken, he was able to establish good rapport with the seamen with whom he worked, eventually publishing two collections of stories based on his experiences with the well-travelled sailors. Because Brückner was so talented, much was expected of him. After 1914, he added __________ *When the Grand Duke attended divine service in Weimar, the Municipal Pastor demanded that Pastor Brückner shave off his beard, which resembled that of the Grand Duke; but Brückner refused, he told me. In Hoboken, Brückner knew quite well the Austrian peasant liberator Hans Kudlich (1823-1917), who lived there as a physician.--Author's note. __________ to his role as Seamen's Chaplain that of Pastor of St. Matthew's Church in Hoboken. He also became Professor of Church History at Hartwick Seminary (founded in 1815), and performed many other duties as well. In 1917, as Brückner was preparing for the Good Friday service, he was taken in custody and placed in internment by the United States Government. Not until seven months later did the authorities finally become convinced of his innocence and let him go, whereupon Pastor Brückner returned to the Seamen's Mission and St. Matthew's Church in Hoboken. Brückner received his doctorate in theology in 1925 from the University of Jena. Over the years, he became quite bilingual, writing poems in English in addition to the German poetry he had composed since his youth. Brückner had come of age at the time of Impressionism, and his poems reflect the moods, pains and joys of the moment. Seeing Weimar Again What has happened in the town I've not seen for so long? Has it stayed the same, remained true? Can I love it as dearly as ever? Does classical air still blow damply through the Fürstengruft? Do those we called "waifs" still wander around? Does the weather prophet still stand at the Lotteplatz, gazing skyward? Do those two earnest birds still promenade in the dress and style of Liszt? Are the girls as nice as ever? The old gentlemen as serious, as dapper? Do evening strollers, deep in thought, still step in puddles? Is art still honored, and the artist? Do folks still get thirsty, love their bratwurst, go out after church? Do they still use up their salaries and pensions properly, buying rounds? Do they take walks in the park, the fields, finding refreshment in nature? Are they still writing memoirs? Telling stories? Hazarding an article or poem that, if not too bad, might even get printed in the Deutschland? Blessed were the golden summer days When my hometown held me snug and warm I know a house that still stands there Where all was done for love of me Where walls united us with friends Forever blessed: my parents and their home. Brückner was very loyal to Germany. During the First World War, Germans in America encountered difficulties as the subjects of a hostile power. Brückner wrote: My soul senses peril Is this your hour of need? Woe to us in foreign lands, with no way, no sword The struggle and cross and garlands are denied us We are left with hearts to bleed, hands to pray Left to die ourselves Should the Fatherland die. Brückner relinquished his dream of his German home and stayed in Hoboken, which he saw in a poem as follows: Evening in Hoboken Across the river flood waves of people on fast white boats thousands upon thousands and always more the army of work pushes home tired people: no dream of victory livens their hearts their souls ask only not to be defeated to how many does life grant this wish? A day like all others pressing cares weigh on today, on tomorrow all eyes on one thing all minds with one thought: the yellow metal! the only hope they know to escape life's troubles and at the end, betrayed they have simply pulled their master's cart. They do not see what pours from heaven how beauty flows from supernatural springs how the narrow world widens the earth: transient the giant city: a fortress no longer the greater eternity all around telling us: you can't be constrained forever only will it and you'll take flight They talk, stare, tired and flat blinded by the heavens' glow turning away from the golden light they don't understand the language of the universe alien the sun from which they sprang alien the earth on which they walk a poor people, a forlorn generation they've lost their goal, thrown away their right. In April 1911, Brückner was asked to speak on behalf of Christianity at a socialist meeting in Hamburg. Since it was to be a gathering of seamen, he felt duty-bound to accept the invitation. At the time, Social Democratic attempts to gain a political voice were considered dangerous agitation against Kaiser Wilhelm II, the German Empire and the Hamburg-America Line. In front of over 500 sailors, Brückner expounded his views. Predictably, the debate soon centered on one question: to have a bourgeois society or a socialist one? At first, Brückner had an uphill battle, but soon the audience let him speak in peace, with only a few habitual loudmouths continuing to heckle. Gradually, Brückner won over the men assembled before him. When he left at midnight, as scheduled, only the organizers were left in the hall. The socialist paper carried an account of the meeting, only to be forced by a letter of correction to acknowledge that the pastor alone had gone home vindicated that night. In widely-distributed leaflets, Brückner criticized the failings of various classes; his efforts found great resonance among the seamen. Pastor Brückner chose his own ending. On February 3, 1957, in his own Church of St. Matthew's, he celebrated the 50th anniversary of his ordination and, at the same time, retired. Only two days later he went to his eternal rest. Growing Responsibilities From the beginning, the work of the Seamen's Mission in the Port of New York had a limited focus, but a wide and encompassing scope. In Hoboken alone, an average of 2000 sailors could be found at any given time on the German ships docked there. The reading and writing rooms and the offices of the Seamen's Home were always full. Over 18,000 people visited the reading room in 1908; over 19,000 in 1909. In 1908, 1313 sailors attended religious services; in 1909, this number grew to 1708. Such figures vividly convey the extent of the Mission's activities. Of special importance were the services rendered to "tramp" ships and other ships that seldom made port in Germany (such as those of the Atlas Line, which sailed to the West Indies, South America and West Africa). The crews on such vessels, like those on ships under a foreign flag, had a high rate of turnover. The sailors who "signed off" were always in urgent need of accommodations, given the housing conditions on shore. Not all of the shipping masters were honest or reliable, so helping sailors to fight for their rights was also part of the Mission's work. Moreover, many seamen, in the spirit of the old saying, "What good is a sailor's money if he falls overboard?" would drink or gamble their wages away in a few days. The Seamen's Mission tried to help the men save their money. So successful was this effort that, in the peak year, half a million dollars was saved, most of it being sent home to the sailors' families. Progress like this made the seamen happier and more independent. Indeed, some who now live comfortable lives with families and businesses of their own first saved their money at the Seamen's Home. The Seamen's Mission always warned the men: Anyone who deserts his ship, misses its departure, or fails to report back to his line after being released from the hospital will be in the United States illegally. To legally immigrate, an individual had to prove what ship he came on. Such proof could be obtained only from the shipping line or the German Consulate. Shipping lines would not provide such evidence for deserters, who had, after all, broken their contracts; nor would the Consulate offer help, since the men in question no longer wished to be subjects of the German Empire. But the illegal immigrants could not become American citizens. Only legal immigrants who had been in the States more than five years were eligible to be granted American citizenship. In America the good jobs and better-paying career opportunities were open to American citizens alone, while anyone deported to Germany could expect to be punished there. Not a day went by at the Seamen's Home without an inquiry from someone whose reckless behavior had brought trouble upon himself. Housemaster Hoffmann The Seamen's Home was enlarged twice in its early years. In 1910, the Mission bought a second building; in 1911, a third. Finally, the old dream of having a boarding house for the sailors could be realized. Initially, there were forty beds. Then a new building opened with fifty-six single rooms, which were completely filled after only fourteen days. The number of deacons at the Mission grew, too. The newcomers, all of whom came from St. Stephan's, were capable men who, out of dedication, worked hard for little pay. Heinrich Hoffmann began work at the Mission on December 3, 1913. Born in Doelau near Greiz on October 12, 1893, Hoffmann had been trained as a locksmith. His father was a well-educated merchant in Doelau. In 1909, Hoffmann went to live at St. Stephan's, where he gained experience in sheltering transients, educating school-aged children, and caring for the elderly. Hoffmann became a permanent member of the Brethren of St. Stephan in 1915. He died on July 30, 1971. Hoffmann was of great service to the Seamen's Mission, particularly during the difficult times of the First and Second World Wars. On April 1, 1919, he was entrusted with the highly responsible position of Housemaster. Emil Boas and Gustav Schwab Two prominent German-Americans, Emil L. Boas and Gustav H. Schwab, were especially supportive of the German Seamen's Mission in Hoboken. Associated with Hamburg-American and North German Lloyd, respectively, Boas and Schwab were instrumental in founding the Seamen's Mission, and both served on its original board of directors. Boas was born in Goerlitz on November 15, 1854. He attended school in Breslau and Berlin, then went to work in Hamburg at the bank of C.B. Richard & Boas, in which his uncle was a partner. After a year in Hamburg, Boas was sent to New York, where his bank represented the Hamburg-American Packet Shipping Company, or Hapag. Founded in 1847, Hapag did not yet have its own offices in New York. When the company did open a New York office in 1892, Boas became its general manager and then, five years later, was put in sole charge of it. Initially Boas had only a few staff members, but by 1912 he worked with hundreds of employees. Boas was active in many local societies and organizations, among them the New York Chamber of Commerce, the Legal Aid Society, the Maritime Association, the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers, the New York Zoological Society, the American Museum of Natural History, the Lawyers' Club, the Unitarium Club, the New York Yacht Club, the National Arts Club, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the German Club, the German Society, the German Chorale and the Germanic Society. He had a large library in his home at 128 West 74th Street, with especially rich holdings in the fields of floriculture and geography. Boas was an enthusiastic flower lover, and his Greenwich estate, "Bonniecrest," had magnificent gardens and greenhouses. Like Boas, Gustav Schwab was a civic-minded businessman and patron of the arts. Born in New York on May 30, 1851, Schwab was educated in Stuttgart, then completed his commercial apprenticeship with North German Lloyd in Bremen. Although his life's work was the promotion and expansion of North German Lloyd, Schwab was also active in many other venues, serving, for example, as a director of several banks. His work on the New York Chamber of Commerce deserves mention, as does the role he played, as Chairman of the New York State Canal Improvement Committee, in the construction of the Erie Canal. No Return to Germany The Seamen's Mission opened its new 56-room building in Hoboken in May 1914. The new reading room welcomed its first visitors on August 3, 1914. In other words, just as the Mission was truly coming into its own, the First World War arrived with its enormous challenges and trials. A flood of German sailors--men unfamiliar with the language or customs of the United States and with no family or friends here--poured into the German Seamen's Home. And the Home was expected to help. At the very start of the war, some 250 German sailors who had been expelled from their ships and had no way to get back to Germany camped out in the main hall of the Seamen's Home. They slept in crowded rows, head by head, foot by foot, and side by side on mattresses donated by the German passenger liners. It soon became clear that these sailors would not be able to return to Germany on neutral ships, as hundreds of German seamen attempting to do just that were seized from Dutch ships and imprisoned in England and France. The stranded sailors--there were 10,000 of them in the New York area alone--had somehow to be accommodated in the States. It was no easy task. At the Seamen's Home in Hoboken, they were fed simple wartime fare: coffee, bread and sausage for breakfast and lunch; potatoes, peas, and soup with meat or sausage at night. The food was prepared at the Seamen's Home by ships' cooks. Some men tried as many as three times to reach home. Each time, however, they were discovered in the bunks or above the boilers of neutral steamers, taken ashore and beaten. As the fame of the German cruiser Emden spread, some of the stranded men set up a small factory where they produced lead models of the celebrated ship. The men painted the models attractively. About 30,000 of these models, bearing the words "Seamen's Aid 1914-1915," were sold for 50 cents apiece throughout the United States. The income sufficed to support about a hundred sailors for a year and a half. Later, when lead became scare and more costly, the men carved wooden Easter rabbits and dolls. The tremendous work being done at the Home inspired Pastor Brückner to write a somewhat naive poem, which appeared on an invitation to the 8th Anniversary celebration of the Seamen's Home on November 3, 1915: Flowers stand on the table today The Seamen's Home is having a birthday It has flourished for eight years Though battered by the storm of war It remains a rock of refuge for thousands Storm or sunshine, we'll stay the course! Though dollars are scarce No one's had to go without We make do with what we have No party this year, as in the past It's time to be serious and frugal We simply pause, gratefully, pensively To look back and say: My, my, how time flies! But someone wanted to mark this day And brought the Home a birthday gift So we'll have a day for gifts When anyone who wants may give one The last Tuesday in November We believe: Aliquid haeret semper -- In other words: whoever sees the Seamen's Home Is glad to contribute a little something. In 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. The German sailors in the Seamen's Home were taken from their lodgings and interned on Ellis Island. Nor did the Home itself escape the war neurosis. In the spring of 1918, the building was confiscated, then occupied by 300 American soldiers. Although the authorities allowed the Mission proper to remain open, it had to find emergency quarters. On October 14, 1919, however, the Mission, with twelve men, moved back to its beloved Home. Roughly 40,000 German seafarers had been stranded in the United States by the outbreak of the First World War. Of these, about 3000 were sent home to Germany from internment camps, about 1000 escaped on their own during the war, and about 1000 died. After the Armistice in 1918, perhaps another 2000 returned to Germany. The remainder, some 30,000, stayed in the United States. After the First World War Plutarch reportedly said: "Navigare necesse est, vivere non est necesse." In any case, so reads the inscription over the entrance to the Seefahrt Building in Bremen. Perhaps Plutarch's observation explains why the post-war recovery--though too slow for the many German seamen who had turn to foreign ships for work--occurred as quickly as it did. Indeed, the Seamen's Home soon could not accommodate the great numbers of German sailors who arrived there. There was never enough room; again, it was necessary to buy and to build. German shipping itself was slower to revive. The first German passenger liner to come to New York after the war was the Hamburg-American steamer Bayern under Captain O. Schwamberger, which arrived on October 1, 1921. A reception was held at the Seamen's Home for the Bayern's crew. German-American brotherhood was pledged, and speakers celebrated the revival of the German merchant marine and the solidification of relations between the United States and Germany. The first Lloyd steamer, the Seydlitz, ... [truncated due to length]