Collections Item Detail

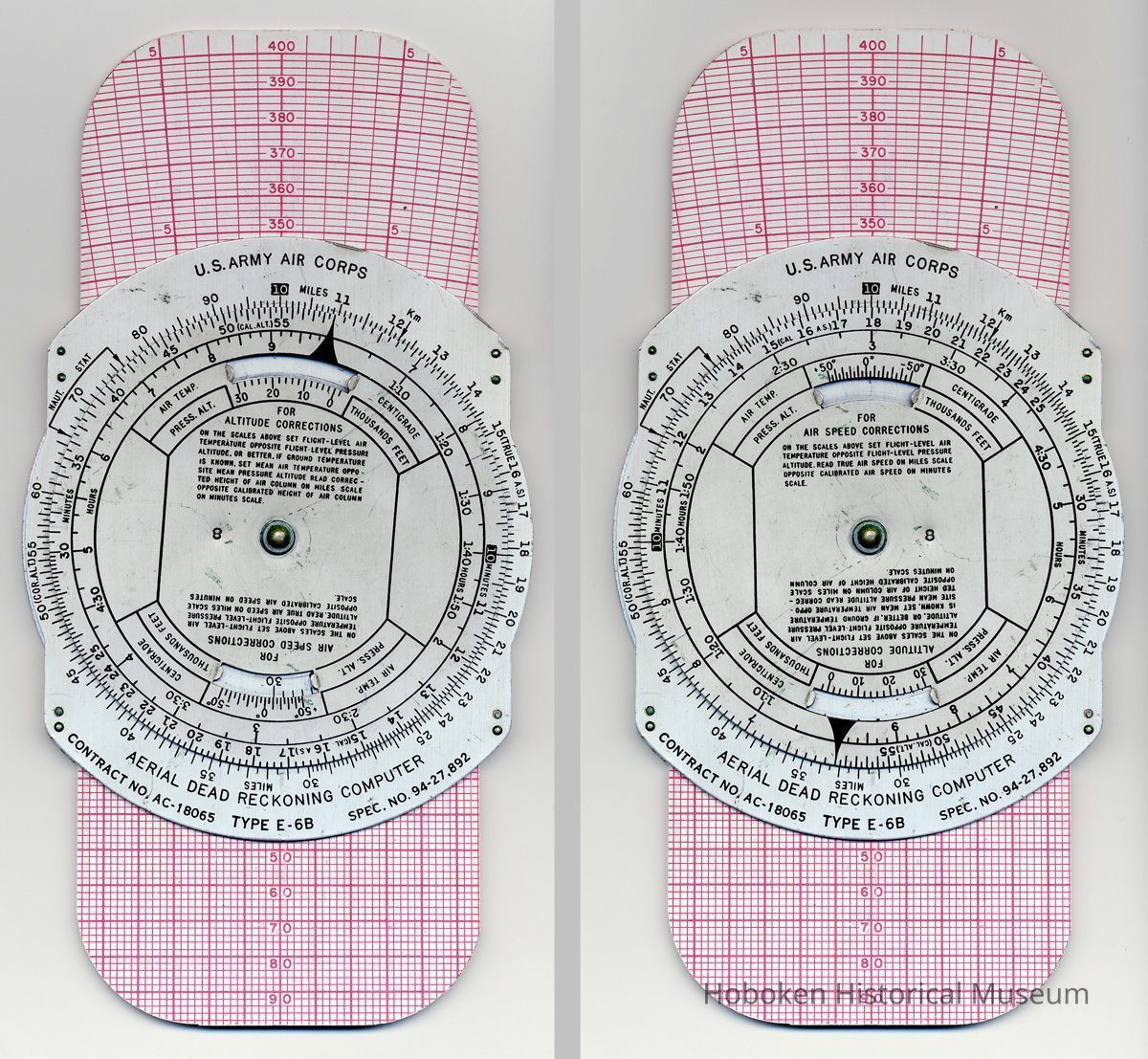

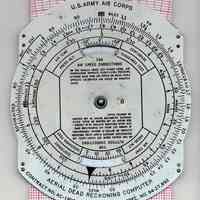

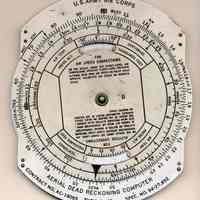

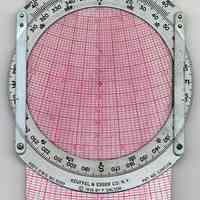

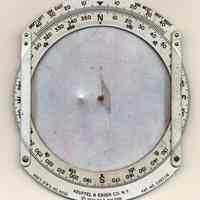

Aerial Dead Reckoning Computer. E-6B. U.S. Army Air Corps. Made by Keuffel & Esser Co., N.Y. N.d., ca. 1940-1941.

2013.005.0077

2013.005

Lukacs, Claire

Gift

Museum Collections. Gift of a Friend of the Museum.

1940 - 1941

Date: 1940-1941

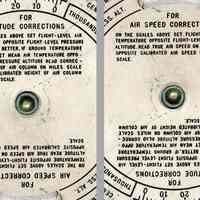

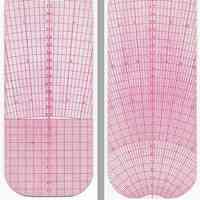

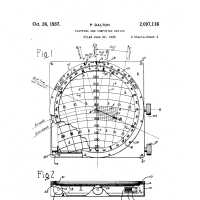

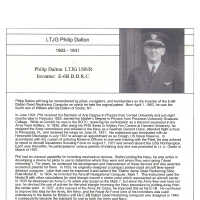

Notes: http://sliderulemuseum.com/WhosWho/Philip_Dalton_Lt_Bio.pdf ==== Text below excerpted from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E6B ==== E6B An E6B flight computer commonly used by student pilots. The E6B Flight Computer, or simply the "whiz wheel", is a form of circular slide rule used in aviation. They are mostly used in flight training, because these flight computers have been replaced with electronic planning tools or software and websites that make these calculations for the pilots. These flight computers are used during flight planning (on the ground before takeoff) to aid in calculating fuel burn, wind correction, time en route, and other items. In the air, the flight computer can be used to calculate ground speed, estimated fuel burn and updated estimated time of arrival. The back is designed for wind correction calculations, i.e., determining how much the wind is affecting one's speed and course. See wind triangle and dead reckoning. Contents 1 Construction 2 Calculations 3 History of the E-6B 4 References in popular culture 5 See also 6 References 7 External links Construction They are usually made out of cardboard and plastic, or aluminum and plastic, with lettering and markings either printed or engraved into the metal. Pivots of metal models (metal with plastic grommet) will wear out the plastic grommet prematurely, causing the wheels to spin freely. This is not beneficial when computing while flying. The cardboard models (except when becoming wet) will outlast the metal versions for most people, and will not develop the "free wheel" even after years of use. Electronic versions are also produced, resembling calculators, rather than manual slide rules. Aviation remains one of the few places that the slide rule still is in widespread use. Manual E6Bs/CRP-1s remain popular with some users and in some environments rather than the electronic ones because they are lighter, smaller, less prone to break, easy to use one-handed, quicker, and do not require electrical power. In flight training for a private pilot or instrument rating mechanical flight computers are still often used to teach the fundamental computations. This is in part also due to the complex nature of some trigonometric calculations which would be comparably difficult to perform on a conventional scientific calculator. The graphic nature of the flight computer also helps catching many errors which in part explains their continued popularity. The ease of use of electronic calculators means typical flight training literature[1] does not cover the use of calculators or computers at all. In the ground exams for numerous pilot ratings, programmable calculators or calculators containing flight planning software are permitted to be used.[2] Many airspeed indicator (ASI) instruments have a movable ring built into the face of the instrument that is essentially a subset of the flight computer. Just like on the flight computer, the ring is aligned with the air temperature and the pressure altitude, allowing the true airspeed (TAS) to be read at the needle. In addition, computer programs to emulate the flight computer functions are also available, both for computers and smartphones. Calculations Instructions for ratio calculations and wind problems are printed on either side of the computer for reference and are also found in a booklet sold with the computer. Also, many computers have Fahrenheit to Celsius conversion charts and various reference tables. The front side of the flight computer is a logarithmic slide rule that performs multiplication and division. Throughout the wheel, unit names are marked (such as gallons, miles, kilometers, pounds, minutes, seconds, etc.) at locations that correspond to the constants that are used when going from one unit to another in various calculations. Once the wheel is positioned to represent a certain fixed ratio (for example, pounds of fuel per hour), the rest of the wheel can be consulted to utilize that same ratio in a problem (for example, how many pounds of fuel for a 2.5-hour cruise?) This is one area where the E6B and CRP-1 are different. Since the CRP-1s are made for the UK market, they can be used to perform the added conversions of Imperial to Metric units. The wheel on the back of the calculator is used for calculating the effects of wind on cruise flight. A typical calculation done by this wheel answers the question: "If I want to fly on course A at a speed of B, but I encounter wind coming from direction C at a speed of D, then how many degrees must I adjust my heading, and what will my ground speed be?" This part of the calculator consists of a rotatable semi-transparent wheel with a hole in the middle, and a slide on which a grid is printed, that moves up and down underneath the wheel. The grid is visible through the transparent part of the wheel. To solve this problem with a flight computer, first the wheel is turned so the wind direction (C) is at the top of the wheel. Then a pencil mark is made just above the hole, at a distance representing the wind speed (D) away from the hole. After the mark is made, the wheel is turned so that the course (A) is now selected at the top of the wheel. The ruler then is slid so that the pencil mark is aligned with the true airspeed (B) seen through the transparent part of the wheel. The wind correction angle is determined by matching how far right or left the pencil mark is from the hole, to the wind correction angle portion of the slide's grid. The true ground speed is determined by matching the center hole to the speed portion of the grid. The mathematical formulas that equate to the results of the flight computer wind calculator are as follows: (desired course is d, ground speed is Vg, heading is a, true airspeed is Va, wind direction is w, wind speed is Vw. d, a and w are angles. Vg, Va and Vw are consistent units of speed. is 22/7) Wind Correction Angle: True ground speed: Wind Correction Angle, in degrees, as it might be programmed into a computer (which includes conversion of degrees to radians and back): True ground speed is calculated as: History of the E-6B The device's original name is E-6B, but is often abbreviated as E6B, or hyphenated in other variations for commercial purposes. The E-6B was developed in the United States by Naval Lt. Philip Dalton in the late 1930s. The name comes from its original part number for the U.S Army Air Corps in World War II. Philip Dalton (1903–1941) was a Cornell University graduate who joined the United States Army as an artillery officer, but soon resigned and became a Naval Reserve pilot from 1931 until he died in a plane crash with a student practicing spins. He, with P. V. H. Weems, invented, patented and marketed a series of flight computers. Dalton's first popular computer was his 1933 Model B, the circular slide rule with True Airspeed (TAS) and Altitude corrections pilots know so well. In 1936 he put a double-drift diagram on its reverse to create what the US Army Air Corps (USAAC) designated as the E-1, E-1A and E-1B. A couple of years later he invented the Mark VII, again using his Model B slide rule as a focal point. It was hugely popular with both the military and the airlines. Even Amelia Earhart's navigator Fred Noonan used one on their last flight. Dalton felt that it was a quickie design, and wanted to create something more accurate, easier to use, and able to handle higher flight speeds. So he came up with his now famous wind arc slide, but printed on an endless cloth belt moved inside a square box by a knob. He applied for a patent in 1936 (granted in 1937 as 2,097,116). This was for the Model C, D and G computers widely used in World War II by the British Commonwealth (as the "Dalton Dead Reckoning Computer"), the U.S. Navy, copied by the Japanese, and improved on by the Germans, through Siegfried Knemeyer's invention of the disc-type Dreieckrechner device, somewhat similar to the eventual E6B's backside compass rose dial in general appearance, but having the compass rose on the front instead for real-time calculations of the wind triangle at anytime while in flight. These are commonly available on collectible auction web sites. The U.S. Army Air Corps decided the endless belt computer cost too much to manufacture, so later in 1937 Dalton morphed it to a simple rigid, flat wind slide, with his old Model B circular slide rule included on the reverse. He called this prototype his Model H; the Army called it the E-6A. In 1938 the Army wrote formal specifications, and had him make a few changes, which Weems called the Model J. The changes included moving the "10" mark to the top instead of the original "60". This "E-6B" was introduced to the Army in 1940, but it took Pearl Harbor for the Army Air Forces (as the former "Army Air Corps" was renamed on June 20, 1941) to place a large order. Over 400,000 E-6Bs were manufactured during World War II, mostly of a plastic that glows under black light. (Cockpits were illuminated this way at night.) The base name "E-6" was fairly arbitrary, as there were no standards for stock numbering at the time. For example, other USAAC computers of that time were the C-2, D-2, D-4, E-1 and G-1, and flight pants became E-1s as well. Most likely they chose "E" because Dalton's previously combined time and wind computer had been the E-1. The "B" simply meant it was the production model. The designation "E-6B" was only officially used on the device itself for a couple of years. By 1943 the Army and Navy changed the marking to their joint standard, the AN-C-74 (Army/Navy Computer 74). A year or so later it was changed to AN-5835, and then to AN-5834 (1948). The USAF called later updates the MB-4 (1953) and the CPU-26 (1958), but navigators and most instruction manuals continued using the original E-6B name. Many just called it the "Dalton Dead Reckoning Computer", one of its original markings. After Dalton's death, Weems[3] updated the E-6B and tried calling it the E-6C, E-10, and so forth, but finally fell back on the original name, which was so well known by 50,000 World War II Army Air Force navigator veterans. After the patent ran out, many manufacturers made copies, sometimes using a marketing name of "E6-B" (note the moved hyphen). An aluminium version was made by the London Name Plate Mfg. Co. Ltd. of London and Brighton and was marked "Computer Dead Reckoning Mk. 4A Ref. No. 6B/2645" followed by the arrowhead of UK military stores. During WWII and into the early 1950s, The London Name Plate Mfg. Co. Ltd. produced a "Height & True Airspeed Computer Mk. IV" with the model reference "6B/345". The tool provided for calculation of the True Air Speed on the front side and Time-Speed calculations in relation to the altitude on the backside. They were still in use throughout the 1960s and 1970s in several European Air Forces such as the German Air Force until modern avionics made them obsolete. ==== Text about when Army Air Corps became Army Air Force from: http://www.aafha.org/aaf_or_aircorps.html ---- The following question arose during planning for the memorial: should Army aviation in WW II be identified as the Air Corps or as the Army Air Forces? This is not a new question. It is a “frequently asked question” by people interested in the history of military aviation. The following paragraphs explain the situation. U.S. Army personnel have traditionally been assigned to branches: Infantry, Artillery, Air Corps, Quartermaster Corps, Corps of Engineers, etc. Branches were generally responsible for training and materiel, although their roles changed from time to time. Operational commands, such as combat divisions and corps, integrated personnel from multiple branches; e.g., Infantry, Artillery, Quartermaster and so on. The Air Corps became the branch for Army aviation in 1926. A few years later, in 1935, General Headquarters (GHQ) Air Force was created for operational aviation units. This arrangement existed in the period leading up to United States entry into WW II. There were two aviation organizations: the Air Corps managed materiel and training and GHQ Airforce had operational units. The Army Air Forces (AAF) came into being on June 20, 1941, six months before Pearl Harbor. As war approached, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall saw the need for a stronger role for Army aviation. Consequently they created the Army Air Forces with General H. H. (Hap) Arnold as its head. ==== Status: OK Status By: dw Status Date: 2013-04-08