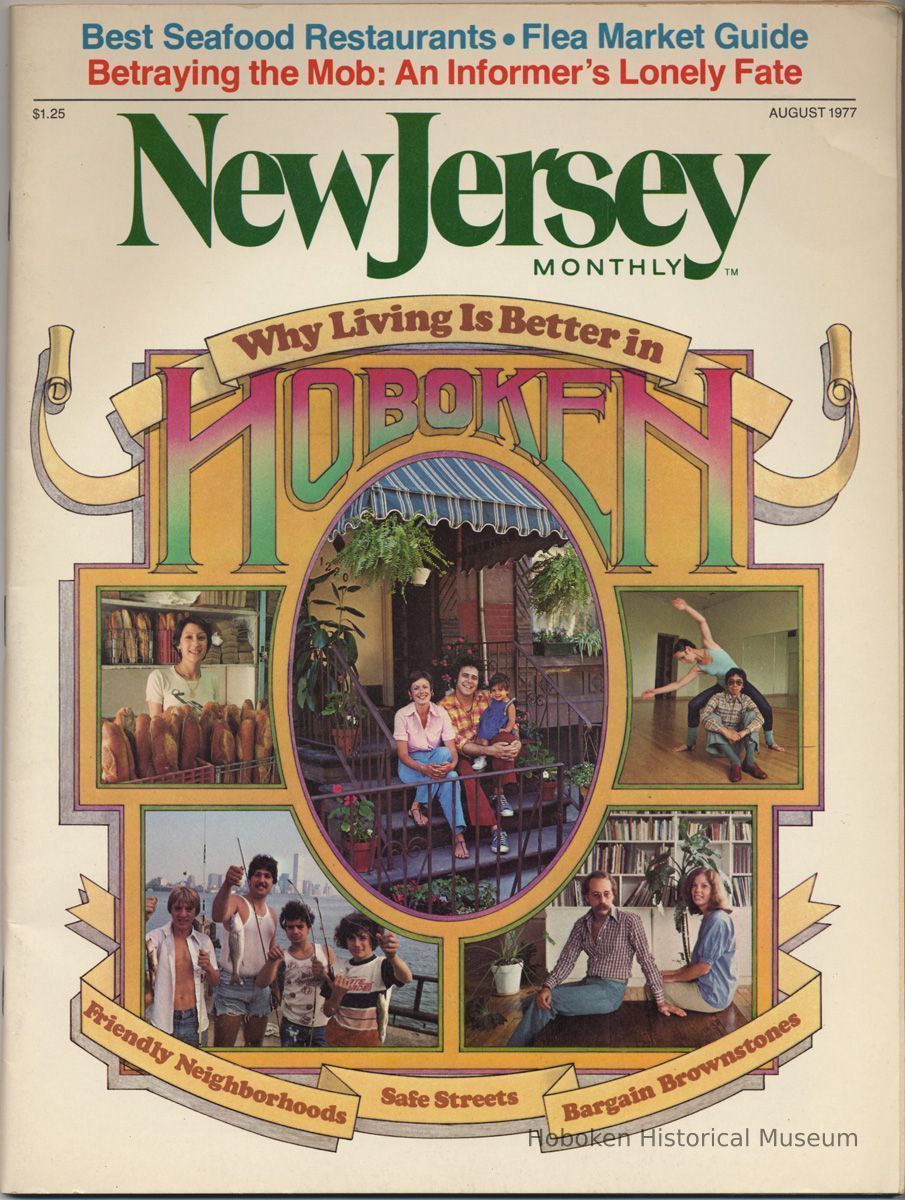

Article: Living High in Hoboken. By Stuart James. Published in New Jersey Monthly, Aug. 1977.

2012.016.0006

2012.016

Martinez, Arturo & Pat

Gift

Gift of Arturo & Pat Martinez.

1977 - 1977

Date(s) Created: 1977 Date(s): 1977-1977

Notes: Archives 2012.016.0006 - article in New Jersey Monthly, Vol. 1, No. 10, August 1977. Featured article on cover, titled: Why Living Is Better in Hoboken. Friendly Neighborhoods. Safe Streets. Bargain Brownstowns. [beginning of article, page 38] Living High in Hoboken. Yes, Hoboken - with its friendly neighborhoods, safe streets, ethnic markets, loft apartments, and bargain brownstones by Stuart James photography by Carroll House / Herb Goro When New York City's first tourist, Henry Hudson, anchored the Half Moon off what is now Battery Park and disembarked to claim real estate for his queen, he was promptly mugged by a party of irate Manna-Hatta In- dians. After a harrowing escape, he crossed the bay and dropped his hook in a cove off Hoboken. The natives were friendlier. The only thing that has changed in 368 years is that the exodus to Hoboken is gain- ing momentum. On any balmy weekend, carloads of middle-class refugees from New York, Con- necticut, and other parts of New Jersey can be seen cruising the streets of Hoboken for bargain brownstone housing. Through the Lincoln and Holland tunnels, across the George Washington Bridge, the brownston- ers come in droves, leaving the cash- conscious Manhattan skyline behind. Their thoughts turn away from muggings and monumental rents, from dreams of unafford- able communities like Brooklyn Heights and Park Slope, and turn instead to visions of rooftop gardens, marble fireplaces hiding behind plywood and plaster, to stained-glass transoms over the doors, to homes of their own that they can actually be paid to restore, to a town where they can feel safe walking the streets at four in the morning. The brownstone revival came to Hoboken -- Stuart James is a freelance writer who doesn't understand what there is about the name Hoboken that makes a total stranger to the place fall down laughing. ---- in 1971 in the wake of a federally funded Model Cities program that brought a shower of cash to the community. The program has now been replaced by the Community De- velopment Agency, but the bureaucrats are still bearing gifts - mostly in the form of 3 percent remodeling loans, which the agency is practically begging homeowners to take. Once plans for renovation are submitted to the agency, they in turn push through a stan- dard 12 percent loan with a local bank. When the work is completed and okayed by an in- spector, a cash grant is issued to the homeowner, bringing the actual amount of interest paid down to 3 percent. It has been six years since the program be- gan, and five hundred homes are in various stages of restoration; not a single homeowner has defaulted on a loan. More than $50 mil- lion in public and private funds has been pumped into improvements in Hoboken - from newly renovated middle- and low- income housing units to remodeled store- fronts on the main streets. While the days of the $20,000 brownstone are gone, it is still possible to find a house in Hoboken for a fraction of what it would cost in New York, and considerably less than a house in the suburbs. Nick and Lisa Borg bought their brown- stone on Garden Street just a year ago for $37,000. Their remodeling is far from com- plete, but with the small amount done - walls removed, brick walls exposed and pointed, floors refinished, two and a half new baths installed, and new plumbing and wir- ing - they could sell the house tomorrow for $50,000. One of the most unusual renovations in Hoboken is a ninety-seven-year-old Baptist church that Mel and Cathy Garfinkel bought three years ago for $25,000 and are currently remodeling. The top floor has been com- pleted - one vast, cheerful room of 1,700 square feet with a cathedral ceiling and a stained-glass window that dominates one end of the room. In most places it would be impossible to find mortgage money and improvement loans to buy and remodel a church. Not so in Hoboken. With the assistance of the Com- munity Development Agency (CDA), the Garfinkels borrowed $12,500. They have done their own contracting, hired workers, and whenever possible, done the work themselves. Still gathering the courage to get serious about remodeling the ground floor, the Garfinkels gaze thoughtfully at the large sunken pool in one end of the huge room. It is empty of water now, but was once used for immersions. "We don't know what we're going to do with this," Mel said, "but it might be interesting." When Betty and George Fitzenrider moved to Hoboken after a couple of murders in their New York City neighborhood, they bought a hundred-year-old house, and were immediately introduced to some of the prob- lems of renovation. The first time they turned [end page 38] [page [39] is full page uncaptioned photo being an elevated (aerial?) view looking northwest at the 700 block of Washington St.; seen are the storefronts and signs on the west side of the street; at the top left corner is the Garden Street side of the Brandt School.] [caption top photo page 40] Illustrator Babette Marchand has a clear view of the Manhattan skyline from this fourth-story loft and studio in Hoboken. [caption bottom left photo page 40] When Jonathan Santlofer first showed this loft to wife Joy, she cried. But she's smiling now. on the heat, their boiler burst and flooded the basement. The agency came through with an im- mediate loan and the remodeling began with a new furnace and pipes. When they were finished they had $45,000 invested in their home, but it is a mansion-like townhouse on what used to be known as "Doctor's Row." The house has high-ceilinged rooms, tall windows, French doors, and six working fireplaces. While there are numerous ways to find a brownstone - cruising the streets, following up want ads in the papers - most newcom- ers find their houses through Realtor Mau- reen Singleton, a one-woman booster com- mittee who moved to Hoboken in 1970. Singleton bought her own brownstone for $22,000 back then, and spent $15,000 on the renovation. The four-story house has four bedrooms, a kitchen, living room, laundry room, and a basement apartment, and is now valued at $55,000. Brownstone renovation has been an ob- session with Singleton from the beginning, and she quickly learned the history of the buildings and what to look for: stained glass in the fan-shaped transoms, molded ceilings and coffin corners, carved newel posts, and double-parquet floors with patterns in a va- riety of exotic woods. "In the earlier days the brownstoners were scavengers," she said. "If a building was being gutted for renovation you'd find brownstoners digging through the rubble looking for old bricks, brass fixtures, wood panels, anything that was old and in good condition. There was one woman who always wore the same old coat with huge pockets, and she carried string and a screw- driver with her at all times. It's different now, of course, because the builders are finding they can sell those things." * * * * Off Castle Point Terrace and Doctor's Row, south of the few treelined blocks of Bloomfield, Garden, and Hudson streets, Hoboken has a shabby look, run down, like a comfortable old sweater with the elbows out. Downtown. North of the Erie Lackawanna tracks, from First to Fifth streets, running east and west, there is the musical staccato of Spanish being spoken, squealed, and shouted. And laughter. The City Hall is on Washington Street, the main drag, and it is monstrous, a building so ugly it has charm. Pigeons roost in the eaves, walk the ledges, whirl and soar over the but- tressed walls. "They ain't so dumb," said an old man sitting on one of the flag-colored benches. "They know where to get the handouts." [end page 40] [caption top photo page 41] Photographers Naomi and Dennis Simonetti relax under a $30 aluminum foil ceiling, which took six months to complete. [caption bottom right photo page 41] Virginia Laidlaw and husband Arthur Chu in the dance studio he worked on for a year. This is the area of town preferred by art- ists, writers, and musicians, where a three- room apartment will rent for $150 a month; and loft space, always a premium when there are artists looking for room to work, rents for half what it would cost in New York. Mau- reen Singleton had just received listings for two 2,500-square-foot lofts, and she figured a fair rental would be $350 a month. Loft space has always been limited in Hoboken, but as high taxes drive more and more industry out of town, space is opening up. "Owners of buildings are learning that loft dwellers make excellent tenants," says Singleton. "And the way they fix up a loft at their own expense is really incredible." "Most artists and writers move here to work," says Daniel Manus Pinkwater, a children's book author and illustrator who bought a five-story loft building on the square facing the old Erie Lackawanna Rail- road terminal, remodeled all the floors into living space, and became the world's most affable landlord. His tenants include an opera singer, a professor of mathematics whose wife is a potter, a pair of photog- raphers, and a dance company. On the day we called he was babysitting for all the chil- dren in the building, several dogs, and a cat. "We're just fourteen minutes from mid- town New York," he says, "on trains that are clean, air conditioned, and never crowded. This area appeals to a lot of artists. They live and work here, but they're really oriented to New York." Istvan Ludoviko "Steve" Kilnisan is the unofficial guru of the loft dwellers. Bearded, burly, soft-spoken, he runs "The Magic Foundation [sic - Fountain]," a sandwich/ice cream/health food shop on Third Street that looks exactly like a Dairy Queen. "That's because it used to be a Dairy Queen," he said recently, smiling. "I changed the name." In the dining room Kil- nisan exhibits the work of local artists and photographers. This is the closest thing to a gallery in Hoboken, and it is also the artists' meeting place, message center, and rental clearing house for apartments and lofts. ' 'This [Hoboken] is a good place to work and enjoy your anonymity," said Kilnisan, who came here as a young boy from Budapest in 1957. He left last year, toured the entire coast of the United States, and re- turned. "Hoboken offers a lot," he boasted. "Some days it reminds you of New Orleans and sometimes Le Havre. It's a very pleasant place to live.'' An eager young man collared Kilnisan at the counter, explained that he was looking for an inexpensive apartment. Someone at the South Street Seaport Museum had sent him. [end page 41] [caption top photo page 42] Hoboken native John Amato, owner of Fiore's House of Quality, has been serving their famous homemade mozzarella since he was sixteen. [caption bottom right photo page 42] Shopping for fresh fruit and vegetable bargains on the streets of Hoboken. "You can check the want ads in the Jersey Journal,''' Steve told him, "but the best thing is just to walk along the streets and look for signs in the windows." Then he added: "Don't tell them you're from New York City or the price will go up. Tell them you're from Bayonne." While the brownstoners and loft dwellers were initially attracted to the city by the low-cost housing, they hoped for and found much more in their new surroundings. Hoboken, with its torn-up streets, double- digit unemployment, and old-fashioned ward politics, is also a city of 45,000 people of di- verse ethnic backgrounds. There is the Italian Community, as it is called by the politicians, an extended family where everybody has known everybody else for five generations; brothers, sisters, cousins, often living in the same block. Mostly middle-class, mostly blue-collar workers, people who sweep the sidewalks in front of their houses. The kids who go to col- lege marry and move to Bergen County, coming back in September for the Feast of Madonna dei Martiri fra Molfettesi e Dintorni to eat a sausage sandwich and show the neighbors how they made it. The impor- tance of being Italian was expressed by a wri- ter who moved here from Manhattan ten years ago. "I don't believe in ethnic generalization," he said, "but I believe that Italians tend to be house proud. Other ethnic groups who come here tend to copy the Ita- lians." Hispanics are the newcomers, Puerto Ri- cans and Cubans brought in twenty years ago as cheap labor for the now-defunct Tootsie Roll candy factory. Their numbers have swelled to 20,000 and they are the deprived, the unemployed. They boost the unemploy- ment rate to 18.2 percent (triple the national average), and they lower median family in- come to $7,200 (well below the national av- erage). But they are family oriented, upward striving, eager to get into the middle class, and they are nudging the old Italian families just as the Italian immigrants pushed the Irish and Germans a few generations ago. "I love this place. It's a dump but I love it," said Paul, a young Puerto Rican who declined to give his last name because "the damn cops will beat the shit outta ya if you open your mouth." He was slouched in a chair, eyes wary, holding a quart of beer wrapped in a paper bag. Paul came to Hobo- ken from San Juan when he was three years old. He's twenty now, unemployed, mar- ried, and has one child. "I ain't nothin'," he said. "Got no education. I don't even know what I'm talking about." He laughed and took a drink. Then he sobered, became seri- ous. "My kids gonna go to college," he [end page 42] [caption top photo page 43] At the family-owned L. Policastro Bakery, daughter Flo Castellitto stands behind the bread that is freshly baked every three hours. [caption bottom left photo page 43] Picking native produce in the center of town at the Hoboken Corner Garden. said. "They gonna make something of them- selves or I'll kick their asses." There is little love lost between the upward-striving Italians and Hispanics, but the street battles and fire bombings of 1970 have been replaced with an amicable truce. The black population is small, about 4 percent of the total, and there are still rem- nants of the Irish and German populations that once flourished. Several thousand East Indians live here, originally drawn to Stevens Institute, where they studied engineering. "In India," said a member of this group, himself an accountant for a New York firm, "everybody knows about three places in America: New York, Hollywood, and Hoboken." Street violence is almost nonexistent in Hoboken, a prime attraction for battle- scarred veterans of New York's five boroughs, as well as for the old-timers who stayed on. "You feel safe walking the streets at 4 A.M.," said brownstoner Nick Borg. "A while back my wife was attacked by a crazed cat," said Manus Pinkwater. "And people on the other end of town were talking about it a week later." One of the reasons Lorraine Koehler moved here was to find a safe environment for her six-year-old son, Seth; a place where he could join in the games on the sidewalk and not have to be constantly chaperoned. All over Hoboken, children like Seth can be seen playing and shouting and even hurl- ing insults in different languages across streets they are too little to cross. You can walk end to end in this mile-long city and never be alone. It doesn't take long for faces to become familiar, and outsiders do not go unnoticed. If the boundaries of water and bridges and tunnels truly have any effect on the low crime rate - some theorize that they make it harder for scoundrels to make a clean get- away -the proximity to the water may be one of the most enjoyable natural crime de- terrents yet. Lorraine Koehler says the loca- tion appeals to her and that she feels "very aware of the river, the harbor, the ocean." She smiled when she said that, slightly em- barrassed by the poetic imagery. "It's an ugly little town," she continued, "but the people here are beautiful." It is this general feeling that makes the town so safe. It is also what makes the low- income housing work in Hoboken when it doesn't work elsewhere. * * * * "Family pride," said Walter Barry, presi- dent of Applied Housing Associates, which is the major developer and manager of the [end page 43] [caption center left photo page 44] A lazy afternoon at The Backyard restaurant, which features folk singers on weekends [caption bottom left photo page 44] Every day after school the kids flock to the docks in search of bass and catfish. low-income renovations in the city. "It was the single most important thing we had to work with." Relocation, the dirty word in urban re- newal, was handled with care and with un- derstanding by the Community Development people, and it seems to have set the tone for the entire program. The relocation office was staffed with young Puerto Ricans. Numerous meetings were held with the families that had to be moved. A cash grant - that magic word in Hoboken - of up to $4,000 was given to each family, plus help in relocating and a promise that they would have prefer- ence in renting the new apartments when they were ready. The old buildings, though sound in struc- ture, were completely gutted and rebuilt into pleasant modern apartments with elevators and garbage compactors. The buildings were also selected because of their proximity to the "uptown" area. "You attach yourself to a stable commu- nity and then build on it," said Barry, ex- plaining the planning that went into the proj- ect. Tenant selection was the next most im- portant factor. They were looking for stable working-class families, and each prospective tenant was interviewed, and his or her cur- rent living quarters examined; employers and social workers were also interviewed, as were the children. "It was important that the first projects set an example," said Barry. "We weren't interested in economics, but we had to have good people. You start off with the premise that immigrant families - I don't care if they're Italians, Jews, or Puerto Ricans - are basically decent if given the opportunity to move upward." Many of the tenants had never seen pilot lights on stoves or trash compactors, so classes were conducted to bring everyone up to date. And everyone was obliged to join a tenants' association. "Peer pressure," said Barry. "Inter- family competition. It's what makes a guy in suburbia keep his lawn nice." The tenants' association has a strong voice in all policies regarding the project. It also has the power to reprimand and even evict a tenant who doesn't fit in. Yet in the five years since Washington Estates was oc- cupied, there has not been a single forcible eviction. The management company coop- erates with meticulous maintenance. Rents are low, each unit geared to the in- come of the occupant. The maximum is 25 percent of the individual's monthly income, with a grant from the government making up the difference. A curious phenomenon is that there is not a single word of graffiti on the pristine yel- low walls of Washington Estates, which oc- cupies a full block. "Pride," explained Barry, beaming. "If Mrs. Cruz sees a kid writing on the walls she'll come out and knock him on the side of the head." Seven projects of various sizes have been completed by Applied Housing, creating 824 new apartments, and two projects are still under construction. Approximately $25 mil- lion has been spent on the renovations. A side effect of the development is that the tenants' association, with few problems on its home turf and a feeling of strength in or- ganization, is now campaigning for other improvements in the neighborhood - new parks, better parking, the planting of trees. And City Hall is listening. The one area that is still in need of a little less listening and a lot more action is the ed- ucational system in Hoboken. Here, the old and new, the poor and rich, all have a bone of contention with the city. Statewide testing invariably ranks Hobo- ken near the bottom of the New Jersey public school system. In recent reading and math comprehension tests that required a score of sixty-five as an acceptable level, only 50 percent of the Hoboken students scored above sixty-five in reading, and only 30 per- cent made it in math. In nearby Passaic, which has an ethnic population similar to Hoboken's, 77 percent of the students were above in reading, and 62 percent in math. The newcomers, who are mostly college educated, are deeply concerned about the quality of the schooling. "It's dreadful," complained Sada Fretz, a book reviewer who moved to Hoboken from the suburbs with her husband and two school-age children. She finally took her children out of the public schools and sent them to private schools in New York City and East Orange. Many of the residents enroll their children in one of Hoboken's five Catholic schools, a by- product of the large Italian population. [end page 44] The brownstoners and loft dwellers with pre-school children recently opened Stevens Cooperative School, a nursery school and kindergarten, as an alternative to the public system. Fifty families are involved, and they pay a hefty tuition of $435 a year. They also look with hope, tinged with cynicism, to a new open-classroom elementary school for grades one through four, scheduled to open this fall. "May I speak frankly?" asked eight- year-old Christopher Barker, a fourth grader whose parents both hold PhD's in biochem- istry. "I don't find the work in my own class very challenging. If you want to know the truth, it's boring. But," he hastens to add, "there are good teachers in the school and they're glad to help if you see them after school. The education is there, but you have to go after it." Perhaps the most difficult area the Com- munity Development Agency has tackled so far is its newest project: tenement rehabilita- tion in the downtown area. Financial assis- tance is now being offered to tenant land- lords, people who will renovate the tene- ments and rooming houses and live in one of the units while they rent the others. "It's tough to get this program moving," said Fred Bado, director of the CDA, "be- cause a slum landlord can make an awful lot of money out of these buildings without doing anything to them." For tenant rehab, as the project is called, the CDA will arrange a 6 percent mortgage for the buyer, and then add substantial cash grants to aid in restoration. Recently, a Hoboken fireman restored a ten-unit building for $87,000. The CDA arranged for a $55,000 mortgage at 6 percent and gave him a grant of $22,000. In another case, an eight-unit building, the restoration cost $48,000. The owners got a $34,000 mortgage at 6 percent and the CDA added a cash grant of $14,000. With this kind of incentive, which offers an average person the opportunity to develop an income property at the same time it improves the neighborhood, the program is gaining momentum. Another CDA program that is just getting off the ground will improve the appearance of the main streets. Any shopkeeper who agrees to restore and remodel a storefront will receive a cash grant of $2,000. Two weeks after the program was announced, forty store owners had made applications and submitted drawings for approval. In the office of Kenneth Pai, chief planner for CDA, are architectural drawings that transform the weather-green, copper-clad Erie Lackawanna Railroad terminal - a crumbling but nostalgic landmark - into a beautiful park-like mall with a complex of boutiques, offices, craft shops, a museum, movie theater, art gallery, and bars (although Hoboken already has seventy-four - an as- tounding number when you consider there are only seventy-nine blocks in the entire town). There are also drawings that show the Hoboken waterfront (scene of the famous On the Waterfront) as a magnificent park. And then there's the battleship. "Craziness!" said a critic of the battleship project. "Do you know how big that battle- ship is? It's bigger than Hoboken." "To be against the battleship in Hobo- ken," said another, "is to be against mother and the American flag." The plan of Richard T. Bozzone Sr. and the Hoboken Battleship Memorial Commit- tee is to bring the mothballed battleship USS New Jersey to Hoboken as a tourist attraction and war memorial. It is generally conceded that the battleship will be coming to town. "It's really not all that bad," said a loft dweller who is basically against the plan. "It's the one way of making sure that the waterfront becomes a park. You can't have tourists stumbling over old pilings. Once the ship is there the park will come." * * * * Hoboken is basically a one-joke town. The same witty saying has been publicly attrib- uted to just about every politician and booster in the city. Mention the magnificent view of New York City and someone tells the story. "People in Hoboken are paying $200 a month for an apartment with this beautiful view of the George Washington Bridge and the New York skyline. Over there people are paying up to $1,000 a month for an apart- ment and all they get to look at is Hoboken.'' The way things are going, New Yorkers may soon be getting their money's worth. [uncaptioned photo at lower right: view southeast of ships docked at Port Authority Pier A and looking across the Hudson River to downtown New York City including the World Trade Center twin towers.] [end] Status: OK Status By: dw Status Date: 2012-04-10

![pp 38-[39]](https://i0.wp.com/d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/5b736570-fa8f-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFeREWG.tn.jpg?w=604&ssl=1)

![pp 44-[45]](https://i0.wp.com/d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/5f07afc0-fa8f-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFeRGyF.tn.jpg?w=604&ssl=1)