Collections Item Detail

Article, magazine: Memories of Augustine Tolton, Black Priest, 1854-1897. Published in The Josephine Harvest, Summer 1986.

2014.025.0420

2014.025

Kiernan, Mel

Gift

Gift of Mel Kiernan.

1854 - 1897

Date(s) Created: 1986 Date(s): 1986

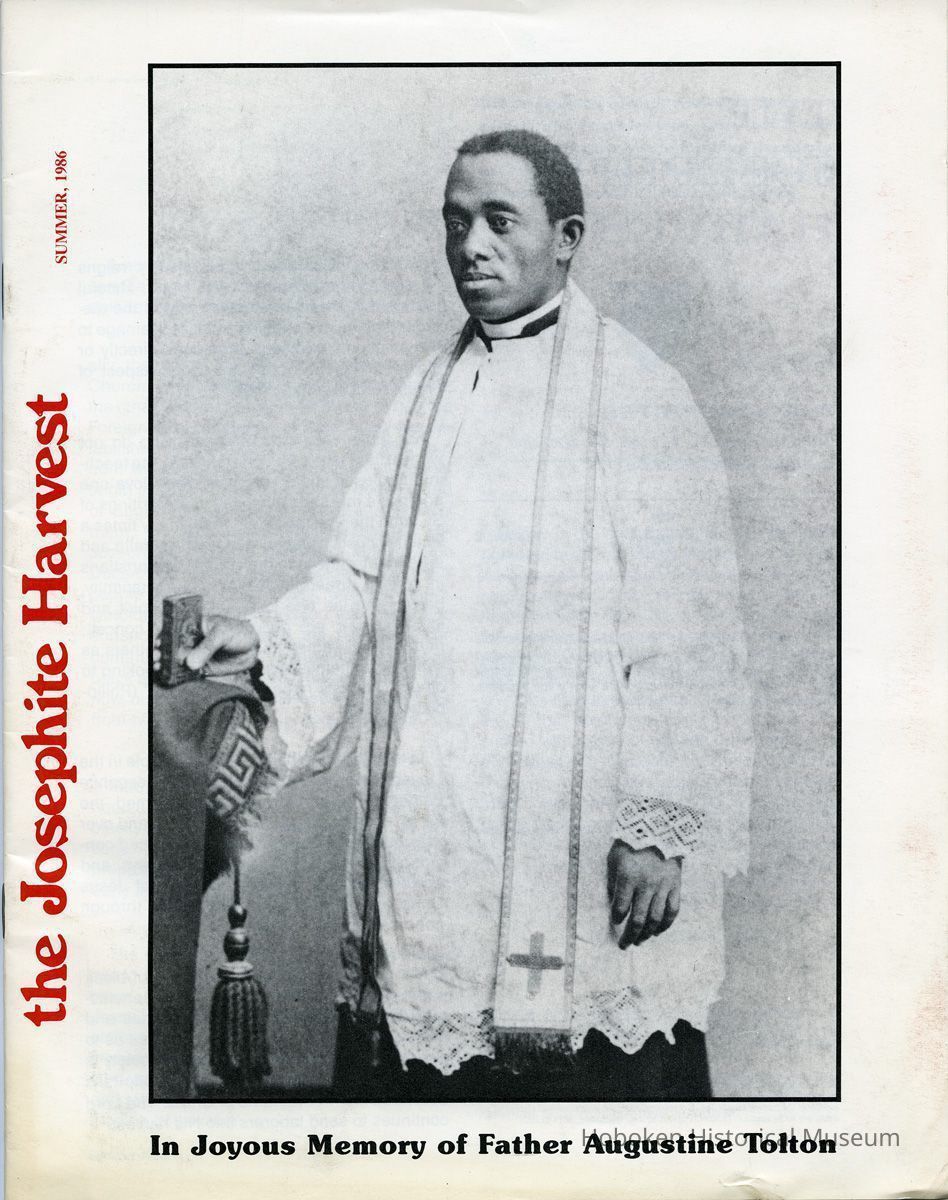

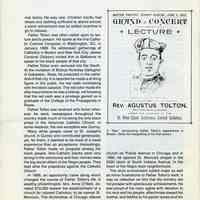

Notes: Archives 2014.025.0420 Magazine article published in: The Josephine Harvest, Volume 88, Number 2, Summer 1986, pp. 8-11. ==== page 8 MEMORIES OF AUGUSTINE TOLTON, BLACK PRIEST 1854-1897 (Selections from Josephite Archives, and “God’s Men of Color, The Colored Catholic Priests of the United States 1854-1954, by Albert S. Foley, S.J., Farrar Straus & Co., New York 1955.) On April 1, 1854, a second son was born to two Catholic slaves living on a plantation near Brush Creek, Ralls County, in northeastern Missouri, not far from Mark Twain’s city of Hannibal on the Mississippi River. The father, Peter Paul Tolton, had been baptized by Father (later Bishop) Peter Paul Lefevre on one of his missionary tours. The colored man was then and continued to be a slave of the Hager family, Catholics of Ralls County. Falling in love with a Catholic slave of the nearby Elliot plantation, he married Martha Jane Chisley in St. Peter’s church, Brush Creek. Raised as a slave of the Manning family in Meade County, Kentucky, Martha was given as part of the dowry when a Manning daughter married a Missouri man named Stephen Elliot. Thus, she came to live in Ralls County. The second son born to the Toltons was given the baptismal name, Augustine, on May 29, 1854. Two more children were born to Peter and Martha before the outbreak of the Civil War. Their long-held hopes for freedom were dashed by the Dred Scott decision of 1857, whereby the Supreme Court returned a slave to bondage. With the taking of Fort Sumter, however, and the start of hostilities, the Toltons made a break for freedom. Peter joined the Union Army, but died in a St. Louis hospital during the war. Martha, with her four children, fled through Ralls and Marion counties, hoping to cross the Mississippi River into Illinois. Almost apprehended by Missourians, who wanted to claim her as a runaway slave, she and the children were rescued by Union soldiers, who happened to come along at the time. They aided her to cross the river to a place south of Quincy, in which city they would settle down in comparative peace. [caption for photo] Father Augustine Tolton (Details of the aforementioned escape were told by Father Tolton and his mother to a Mill Hill Josephite Father during an interview conducted in 1886, and in a speech delivered by Father Tolton in Washington, DC, in January 1889.) ==== page 9 For twelve years, young Augustine Tolton worked as a tobacco stemmer and factory hand. During off seasons from these labors, he attended the Lincoln public school in Quincy. His family were members of St. Peter’s church, where Augustine and his brothers caught the pastor’s attention. The pastor entered them in the parish school, integrating it. There was a furor on the part of parents of white children, but the pastor and Sisters of Notre Dame insisted the black children would stay. And they did and so also the white children. Augustine learned his fundamentals in St. Peter’s school and he also worked there parttime. He tended the furnace for six years. Even at that early age, he had a strong spirit of devotion and spent hours in prayer in the church. On the occasion of his first communion, Augustine was asked by the pastor to consider the priesthood as his vocation. Augustine applied to the local community of Franciscan Fathers but nothing came of that. Yet, some of the Fathers took a special interest in Augustine and gave him private tutoring in Latin, Greek, German, English, History and Geography, in preparation for high school. Mrs. Tolton took a job in northeastern Missouri and remained there, with her children for eleven months. They returned to Quincy, however, because blacks were still being kidnapped and sold as slaves in Missouri. Augustine again worked part-time and was once more tutored by the Franciscan Fathers. The young man yearned for the priesthood. His piety, intelligence, lively mind and modesty caused one of the Fathers to contact the Bishop of the diocese and, subsequently, the Father General of the Franciscans in Rome, urging admission of young Tolton to the College of the Propaganda in Rome. Augustine was accepted. There was jubilation in the Tolton family and among students at the Franciscan college in Quincy. The students took up a collection toward travel expenses, and the Franciscans and the Bishop added further funds. On February 15, 1880, Augustine left Quincy for Rome. The young student distinguished himself by a brilliant course. In May 1883, he received the Tonsure and in 1884, the ‘minor orders.’ In 1885, he received the first of the ‘major’ orders and in 1886, Augustine Tolton was ordained a priest. Father Tolton later described the discussion as to where he would be assigned, whether to foreign missions or to the United States. It was noted that he would be the only Black Catholic priest in America. A cardinal (Simeoni) said, “America has been called the most enlightened nation; we will see if it deserves that honor. If America has never seen a black priest, it has to see one now. Come and take the oath to spend your whole life in your own country.” Father Augustine was ordained on Holy Saturday, April 24, 1886 in the Basilica of St. John Lateran. On Easter Sunday, he offered Mass at the High Altar of St. Peter’s Basilica, usually reserved for the Holy Father. At the tomb of the Apostle Peter, Father Tolton completed his preparation in Rome. In June 1886, Cardinal Simeoni missioned Father Tolton to Quincy. Arriving in New York City on July 6, he offered Mass at St. Mary’s Hospital in Hoboken and on the following Sunday, at St. Benedict the Moor church in downtown New York City. According to accounts, he sang the Mass with a powerful voice; six feet tall, he was an impressive person. On July 25, 1886, in Quincy, Illinois, Father Tolton was named pastor of St. Joseph’s Catholic Church for Negroes. The parish had grown out of a catechism class he had conducted in 1877 at St. Boniface parish. There were 80 members in the parish when Father Tolton assumed the pastorate. The parishioners were desperately poor; total annual collections did not amount to more than one hundred dollars. Father Tolton was confronted with marriage problems at the very outset of his ministry. Normal ==== page 10 family life was rare. Children hardly had shoes and clothing sufficient to attend school; a warm schoolroom was an added incentive to go to classes. Father Tolton was often called upon to lecture and to preach. He spoke at the first Catholic Colored Congress in Washington, DC, in January 1889. He addressed gatherings of Catholics in Boston and New York City. James Cardinal Gibbons invited him to Baltimore to speak to the black people of that city. Father Tolton even ventured into the South. At the invitation of Bishop Nicholas Gallagher of Galveston, Texas, he preached in the cathedral of that city. It is reported he made a striking figure in the pulpit, his red sash contrasting with the black cassock. The red color made the altar boys believe he was a bishop, not knowing that the red sash was a privilege gained as a graduate of the College of the Propaganda in Rome. Father Tolton was received with honor wherever he went; newspapers throughout the country made much of his being the only black priest in the American Catholic Church. In some respects, the one exception was Quincy. Many white people came to St. Joseph’s church in Quincy and contributed generously; yet, for them, it seemed to be more of a novel experience than an acceptance. Interestingly, Father Tolton made no progress among the black people. Non-Catholic blacks were very strong in the community and their revivals were the big social affairs of the Negro people. They kept alive the prejudices against the Catholic Church. In 1889, an opportunity came along which changed the course of Father Tolton’s life. A wealthy philanthropist, Mrs. Anne O’Neill, donated $10,000 toward the establishment of a church for colored Catholics, to be named St. Monica’s. The Archbishop of Chicago offered the post to Father Tolton, to which arrangement the Bishop of Quincy gave his consent. Father Tolton took up residence at St. Augustine’s ---- [caption for illustration] A “flyer” announcing Father Tolton’s appearance in Boston. (Note the misspelling of his first name.) [text in illustration] BOSTON THEATRE. SUNDAY EVENING. JUNE 5, 1892. Grand Concert ••• LECTURE ••• REV. Agustus Tolton, (First Negro Priest in America,) UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE St. Peter Claver Conference, Colored Catholics. ---- church on Prairie Avenue in Chicago and in 1890, he opened St. Monica’s chapel in the 2200 block of South Indiana Avenue, in the heart of the Negro slum neighborhood. The slum environment added major as well as minor frustrations to Father Tolton’s work; it was no reflection on him that the ministry did not prosper with spectacular achievements. He was proud of his color, aglow with devotion to his race and his people, affectionate toward his mother, and faithful to his parish duties and his priestly vows. There were some realizations; he established another chapel at 36th and Dearborn ==== page 11 streets, offering the first Mass there in 1893. He also made friends among the more than 100 priests of the Chicago archdiocese. He journeyed with them to Kankakee in the first week of July 1897 for the annual clergy retreat. It was an excessively hot summer; on the way home, on Friday, July 9, he was stricken by the heat. At the age of 43, Father Augustine Tolton died in Mercy Hospital on that day. He had been a priest for eleven years. His body lay in state in St. Monica’s all day Sunday; thousands of Catholics came from all over the City of Chicago to pay their respects. On Monday, more than 100 priests crowded into the little chapel for the Requiem Mass. Then, Father Tolton’s body was taken back to Quincy for burial, accompanied by his mother, sister and brother. The Mass of Burial was offered in St. Peter’s church, because St. Joseph’s parish no longer existed; it had succumbed to numerous adversities after Father Tolton left for Chicago. One of the largest crowds ever to assemble followed the hearse to St. Peter’s Cemetery, where Father Tolton’s body was interred. As Father Foley noted, a modest marker was erected over the grave but the real monument to Father Tolton is the procession of other black priests who have followed in his footsteps, having understood the true significance of his vocation as a pioneer in the erasing of unwritten laws and in the elimination of unspoken prejudices. More than anyone else, Father Tolton dispelled the doubts and suspicions that remained as vestiges of the thought-ways of whites from pre-Civil War days. He proved that, given intelligence, holiness, courage, and the perseverance he manifested in his holy life, the full stature of a good priest could be achieved by men of all backgrounds and origins. ==== ==== Status: OK Status By: dw Status Date: 2014-07-01