Collections Item Detail

CD-ROM: The 1900 Hoboken Pier Fire: What Happened. Offline version of website from Pier3.org. 2002.

2002.214.0087

2002.214

Staff

Found in Collection

Museum Collection.

2002 - 2002

Date(s) Created: 2002 Date(s): 2002 Level of Description: Item

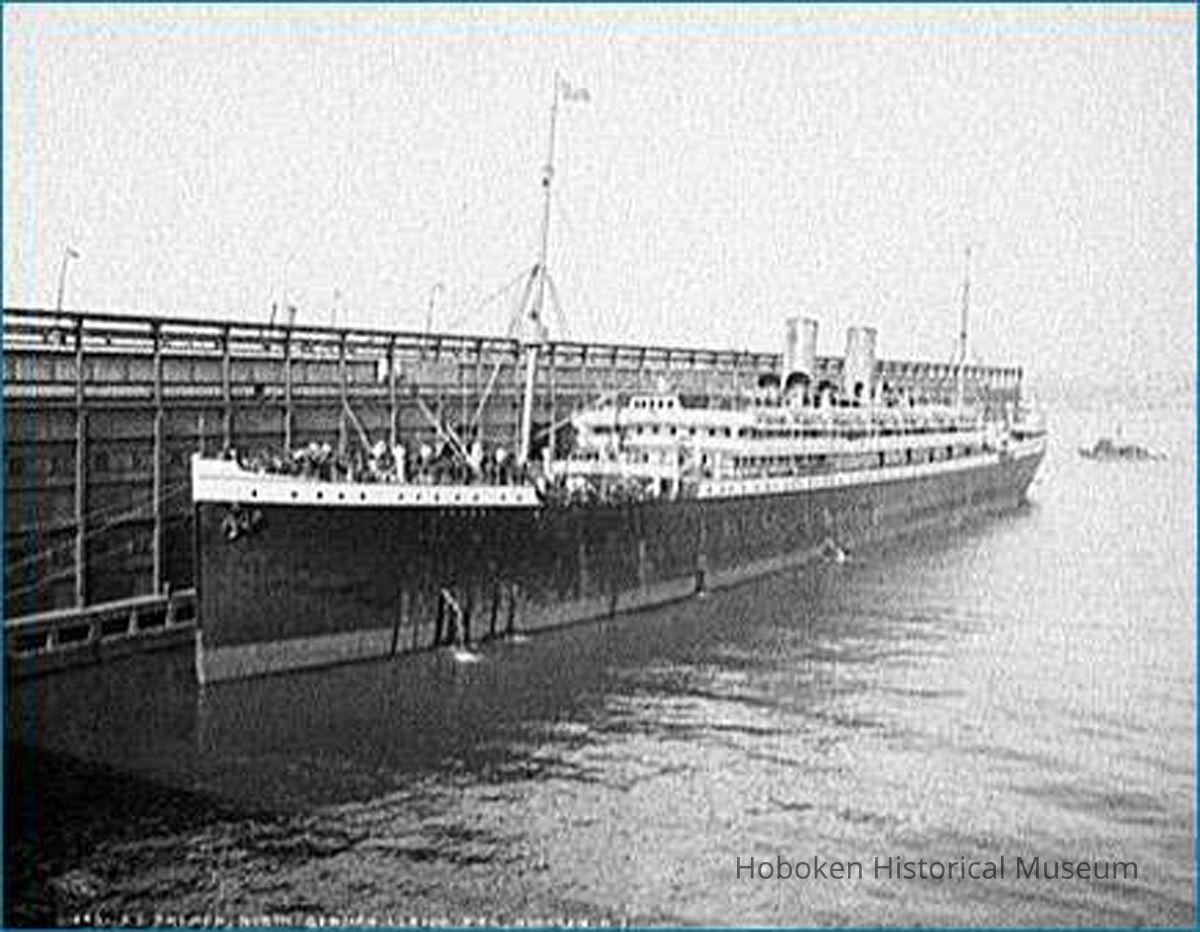

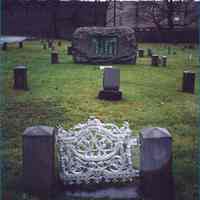

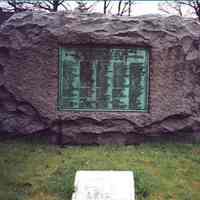

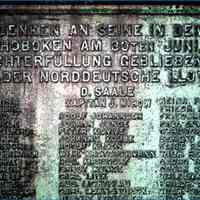

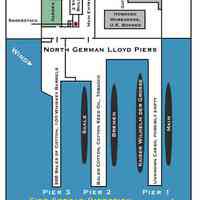

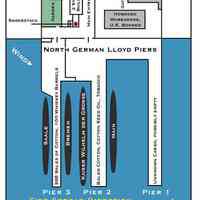

Notes: Home What Happened? Visuals Casualties Communicate Bibliography Help Reason Explanation of events, dedication to victims, and preservation of memory. Some Facts 1. June 30th, 1900 2. Hoboken, NJ 3. At North German Lloyd Piers 4. 326 to 400 dead 5. $5 million in property loss Helpful Hints This site is optimized for Microsoft Internet Explorer, the Macromedia Flash player, and the Windows Media Player Welcome to Pier3.org This website begins right here, just as the fire that destroyed the North German Lloyd docks at Hoboken began at pier 3. That is a known fact, though there are many other events that happened that day and the following days, that remain a mystery lost in the chaos of June 30th, 1900. Hopefully, this website can attempt to create some form of digital record, detailing the series of events that unfolded during the fire. I appreciate the various sources cited in the Bibliography section, for they have helped me to learn so much when I knew so little. This "offline" version of the website was made to be displayed at the "Destination Hoboken" exhibit, to share what I know and what I have learned from many who have contributed in their own, unique way. Thank you for browsing! 04/17/02 Added a new image, a postcard of the procession to Flower Hill Cemetery, under the "Visuals" section. 01/18/02 More names have been added to the "Casualties" section. There are now a total of 244 entries listed. 01/13/02 Photos of the mass grave at Flower Hill Cemetery have been added to the "Visuals" section. Did You know? In 1900, a little more than Twenty percent of the population in Hoboken was German-born. What Happened? It is fairly easy to describe the aftermath of the Great fire of June 30th, 1900. Structures and ships of many kinds were damaged and destroyed, property losses calculated and insurance matters initiated. What is difficult to fully realize, is the exact number of those who lost their lives. Many people drowned in the Hudson River, the intense heat that the steel hulls of the ships so efficiently conducted with horrific results incinerated others. This effect when coupled with the fact that the portholes of the passenger liners were too small to pass through conspired to prevent escape for the visiting weekend tourists and crews of the ships. This means that an exact number of those lost will never be known. The initiator of this tragedy is unknown as well. What started it? The most popular theory is that of spontaneous combustion on such a hot, dry day. Indeed, there was a long period before that day, without rainfall, and the stocks of the pier sheds and warehouses are even more suspicious as possible culprits. It could have been an accident. Maybe it was a carelessly thrown cigarette or a spark from a tool or machinery? It is also speculated, but is considered very unlikely, that the fire was deliberately started. No amount of research can determine the exact cause of the fire or the total number of lives lost as a result. That is due to the fact that there is no more evidence or material that made-up the North German Lloyd pier area in Hoboken. We must be content with what people have written and remembered. The focus of this short history will center on those events that happened during the fire, as well as those that took place in its aftermath. A Little Bit Of Geography And History Geography and History. It is not as frightening as it sounds! I think that it is necessary to realize where the objects in this story were situated and to understand why the two largest German Steamship lines were present at Hoboken in 1900. Sitting on a bench at Pier Park A in Hoboken today and looking over to New York City, you could never imagine what was happening at this spot at the beginning of the last century. The largest ocean liner in the world docked regularly at the piers of the largest passenger shipping company. Immigrants from Europe were arriving in the area by the hundreds of thousands each year, and there were many Germans in Hoboken. Out of Hoboken's total population of 59,000 in 1900, more than 20% were German-born. Indeed, the Germans had already been present in large numbers for almost 40 years, and many had settled down to stay. The German shipping lines, the North German Lloyd and the Hamburg America Line, had bought land next to one another from the Hoboken Land and Improvement Company in the early 1860s. Is of note that the Land and Improvement company was formed by the Stevens family which had developed Hoboken from a swampy marsh land, into an organized and flourishing city. The local economy was very German, driven primarily by the pier facilities of the North German Lloyd and the Hamburg America Line. Hoboken was ideally situated near Ellis Island, and had the necessary infrastructure to promote immigration to and from the area. This was accomplished primarily by the many rail facilities and companies that were all bundled together near the ferry terminals on the Hudson River, ready to spread out to points across the United States. In addition to the shipping companies, many clubs, schools, churches, restaurants, stores, and hotels, such as Meyer's Hotel, which was located not too far from the two shipping lines, were German. There were also Factories of various kinds, some known for their precision equipment such as Keuffel and Esser, that contributed to the growth and importance of the city. Just take a detailed look at a map of the city from around 1900, and look at the names - it seemed like a Teutonic outpost in the glorious days of the Kaiserzeit. Okay, now for some geography: The Map above is from 1900, and the area in blue is Hoboken. The map scale on the bottom right of the map is hard to read, but the total distance on that scale is one mile. This measurement gives an idea of how close everything in the New York City area is. Above, we have a visual guide to some of the places mentioned in the preceding text. The main subject of this website would be the piers of the North German Lloyd shipping line which are in blue. Please note that this map is from 1906, and the piers that were rebuilt after the fire are shown. The map was purchased from the Hoboken Historical Museum and it is absolutely wonderful. You should get one yourself and help support the museum! The places featured in color on this map are in the same positions as in 1900, though the piers looked a little different. The places are: 1. North German Lloyd Line = Blue 2. Hamburg America Line = Pink 3. Ferry Terminals = Yellow 4. Meyer's Hotel = Orange 5. Hoboken Land and Improvement Company = Green 6. Train Tracks and Sheds = Purple Now, since you know some background history about Hoboken, it is time to jump forward to that terrible day of the fire, June 30th 1900. June 30th 1900 That summer day was not so busy for the world's largest shipping company. Saturdays never were. It had not rained for days, was very dry, virtually cloudless, and the wind was blowing from the southwest. That breeze blowing over the Hudson River was to be the vehicle that would help to carry the fire on its destructive path from pier to pier and ship to ship. The only "people" traffic that day would be those who had come to visit the liners of the North German Lloyd which were open to the public for touring. The crews of the ships were at a minimum, as most were away on shore leave before the departure of the ships the following week. Those crewmembers that were present consisted mainly of stewards, who had prepared the ships to be coaled. As a result of this, portholes and ventilators were sealed to keep the coal dust away, and furniture was covered. Following this procedure, about 500 stevedores who were present would begin filling the coalbunkers of the massive ships, a process that was very time consuming. This consisted of the ships being arranged in their docks so that the coalbunker loading doors would be opened on the sides of the ships' hulls, and then numerous coal barges would be brought up along side. The bituminous coal was then deposited by buckets down into the chutes that led to the ship's coalbunkers. This whole situation with all of these coal-loading doors being open made the ships very vulnerable. The only ship that was to sail soon was the Saale. She was fully loaded and was to sail the next morning. The Ships There were 4 ships that day at the North German Lloyd piers, and 2 at the adjacent piers of the Hamburg America line. The North German Lloyd steamer Aller which had been moored on the north side of Pier 3 had left at 11:30 that morning bound for Naples, Italy. On June 30th, 1900, the Lloyd piers, which were 600 to 900 feet long, were arranged as follows The largest of the ships was the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, built in 1897. Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany christened her, in homage to his grandfather, and in direct competition with Great Britain. In 1900, she was still the largest and fastest ship in the world, though that was about to change. Her tonnage approached 15,000 and she had a maximum speed from 21 to 22 knots on average. Later in 1900, the Hamburg America Line steamer Deutschland would soon eclipse those titles. The Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was the last word in luxury and a very profitable and consistent performer for the North German Lloyd. She was also the first of the famous 4-stacker liners, and ushered in 10 years of German domination in Passenger ship size, speed and profitability. She was moored on the south side of Pier 1 on the day of the fire. Moored on the north side of Pier 1, was the new steamer Main. She had just been put into service, and had 4 large cranes for cargo loading. She was a sleek-looking ship with one stack and weighed in at 10,000 tons. Note, "Main" is pronounced as "Mine". Moored at Pier 2, were the steamers Saale and Bremen. Saale, on the south side of the pier, was by far the oldest ship there that day. She was built in 1886 and weighed about 5,300 tons. Since she was older, she was used mostly as a cargo ship in addition to transporting immigrants. The Bremen moored on the north side of Pier 2, was the last of the 4 ships at the Lloyd piers. She had the distinction of being in the first class of ships to be built in Germany that weighed over 10,000 tons. She herself, weighed in at 11,500. Fire The fire started at Pier 3, that much is known. However it must have started, a North German Lloyd watchman who is mentioned in many sources, William Northmaid, first noticed the smoke from coming from the pier. He first saw the fire at 3:55 P.M., but had to get to a telephone to report it. The Hoboken Fire Department Headquarters, which was only two blocks away, logged his report at 4:01 P.M.. Another account, given by former Captain Max Moeller who was now the Chief Inspector of the North German Lloyd piers in Hoboken, stated that the fire had started at 3:45 P.M. In any case, the fire spread quickly, mainly due to the stiff breeze, the old dry wood, and the years of dust that had accumulated from the various cargos that had been in the pier sheds. The wood had been absorbing it for years. Only Pier 1 had a steel frame. It was fairly new and was built in 1897 for the arrival and service of the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. With the wind driving the fire very rapidly, the flames jumped from the pier sheds to the barges and lighters, and then from the barges and lighters to the ships. Many sources state that everything was ablaze in the span of ten to twenty minutes. The Lloyd's Chief Inspector, Max Moeller, went to the end of one of the piers to summon the aid of tugboats to pull the large ships out. During this time he had ordered that important paperwork and money be rushed out of the burning pier offices. A Disaster Seen By Many This fire would be notable for more than the damage it caused, for an estimated one million people living in the area observed it. The smoke cloud that rose up from the fire was so large that it was noticeable for miles. Many people who had gone to the beaches in New Jersey quickly turned their attention to it. Likewise, those living in the tall buildings of Manhattan were able to see it clearly. So did the press. There are actually many pictures that were taken of the fire as it was happening, and many more of the ruins and destruction, taken over the following days. So many people had rarely seen a fire such as this at once. The Tugboats Many Tugboats were now on their way to rescue the great ships. By now, the first of the ships to catch fire, the Saale, had started to drift away from her pier, ablaze. Her crew had quickly cast off her lines but the fire had already leaped onto the ship. Some of her crew was seen hanging over the side of the ship, some on the rudder. Of these, the tugboats and other harbor boats rescued some. Some, who had grown exhausted, slipped away and drowned. It is important to quickly mention that even though so many worked near the water, many did not know how to swim. Many of the pier workers (longshoremen) and stevedores had died this way. Some tried to escape from the burning piers by running through the fire towards Hoboken, and others had no choice but to jump from the burning piers. Next. The Bremen had caught fire, suffering a similar fate as the Saale, drifting slowly and ablaze. Then the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was next. It was decided that she should be rescued first, having some of the weekend tourists aboard, and for her value as the flagship of the North German Lloyd. She was already in a rearward motion through the use of her winches, and the Tugs were ordered by Mr. Moeller to save her first. Two tugs began to pull the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse from her stern, but she was still held by one line by the bow. A brave sailor, Eric Sorenson, had climbed down across the rope; hand over hand, to the pier. He released it and was actually able to escape through the flames. Cheers were heard from the ship as she started to be pulled backwards at about 4:10 P.M. Her bow had caught fire from a burning coal barge that was lashed to her bow as she was pulled into the middle of the Hudson River. Several tugboats were diligently working with their fire hoses to put those fires out and also a small fire that was on her stern. The ships' officers and men had also quickly put out many smaller fires with their uniforms and by other means. The order aboard the ship was exemplary, as Captain Engelbart stood silently on the bridge of the ship, with two pistols drawn. Due to the timely actions of her disciplined crew and the help of the many tugboats that came to her service, no lives were lost on the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse that day. Her damage was minimal by comparison with the other ships. Over 200 feet of paint on the starboard side of her hull had been burned away, mostly from her bow area. The glass in many portholes had burst from the heat, and some things made of wood such as deck planking and lifeboats had been burned. The ship then proceeded upstream to about 46th street off of Manhattan and anchored there. Unfortunately the story was very different for the other three ships. The Saale and Bremen were now drifting and blazing uncontrollably. Many tug boats played their hoses upon the fire; some catching on fire briefly themselves. Many of the crew of both ships swamped the tugboats as they tried to escape. The tug Nettie Tice took off 104 people from the Bremen alone. Meanwhile, the Main which was moored the farthest north, was unable to be freed from her pier. The tugs worked frantically but to no avail. Some forty-four of her crew died, unable to escape her burning hull. She eventually drifted free after her mooring lines burned, with horrible luck she was drifting to where the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse had anchored. The Kaiser was ordered even further upstream as some tugs had finally managed to secure some lines to the Main's rudder. Mr. Moeller then ordered the tugs to drag her to the Weehwaken Flats. The Bremen in the meantime had been moved to the Weehawken Flats as well, which accounts for the many pictures that are available of the two ships burning together. The Saale had drifted as far south as Governor's Island, and was then taken near Communipaw, New Jersey. She arrived just in time, as she began to settle to the bottom within 10 minutes. Her steel hull and superstructure was so hot by now that the water from the hoses of the tugboats hissed as soon as it hit the ship. It must also be said that not all tug boat crews acted so admirably as those presented in the previous paragraphs. Many, lured by the rewards of saving floating barges filled with cotton, coal, or even floating bales of cotton or barrels of whiskey, chose to rescue those instead of people. Though the majority of the tugboats helped that day, more than 100, some were lured by the temptation of profit. Cotton bales could bring in $40.00 apiece, while the coal barges were the most valuable prizes to save. It must be remembered that $40.00 was a good deal of money at the time. There were a few instances where men trying to swim in the water were ignored by these tugs and other harbor boats. A tugboat with salvaged cotton bales. Terrible Moments Some of the most memorable moments were unfortunately horrific. Most centered on the fates of those who could be seen through the portholes of the ships, and could not be saved. At the time, most portholes were too small for an adult to fit through. After this tragedy, their design would be changed and made larger. There were many other instances of horror and tragedy that were noted that day. It is at this point that I would like to quote a section directly from one of the sources listed in the bibliography section, the article from an issue of Sea Classics written by Brad Leonis: "Then the real horror began. Faces and arms appeared at the eleven-inch portholes of the Saale, Bremen, and Main, portholes too pitiably small to permit the passage of any adult body. A woman appeared at a porthole on the Main. She looked down at a half-dozen tugs and 100 men unable to help her. The young woman, a stewardess, began praying loudly. Smoke drifted past her head and flames could be seen behind her. Hoping to save her, one man grabbed a rope, clung to the red-hot side of the Main and with a hose climbed to an adjacent porthole, through which he sprayed water on the creeping flames. He fell. Flames and smoke began to envelope the woman, and she called out "Now listen! Listen! Tell my mother - she lives in Bremen - tell her my last thought was of her - tell her all my money is in the bank - tell her she can have it all - tell her..." Purple fire pulled over her face and with a quick shriek she was gone." For many of the crews trapped below decks, the story had the same terrible ending: "Below decks on the Main dozens of stokers, engineers and stewards died miserably, waiting for death as ten feet of flames roared over their heads and ate downward to them. On the Saale... "It took three hours for those trapped behind the portholes to die. On one of the tugs a catholic priest, Rev. John Brosnan, lifted up his hands and face to those begging "Wasser, Wasser! Ach, Himmel, Wasser!" and gave them Extreme Unction. Men in the tugboats went mad with their inability to save anyone." I think those quotes from the article provide a searing image of the grim reality that was being played out that day on the waters of the Hudson River. Other Damage There were so many watercrafts of various types on the river that 27 of them also caught fire as result of the floating and flaming wreckage. There were no tunnels from New York City to New Jersey yet, so the main source of transportation was by these many and varied boats and ferries. New York City even suffered some fire damage from Hoboken, when the Bremen had drifted to the other side of the Hudson River and had started a small fire at Pier 18. This was the point where she was then towed to the Weehawken Flats, where the Main would later join her. Everyone who was in the area had stopped what he or she was doing to look on in awe. It is true that many people in Hoboken thought that the world was ending because the smoke clouds had turned the bright sky to darkness. Hoboken itself had suffered damage. The Thingvalla Line, which bordered the North German Lloyd piers on the north, also lost a pier to the blaze. The large Campbell's Stores, built at a cost of $1.5 million dollars, and the Hoboken Warehouse which was located on the North German Lloyd property area, were burned down with only a corner of the Campbell's Stores building remaining. A photo of what was left of Campbell's Stores can be seen below: The Aftermath Some of the ships continued to burn for a few more days, or were so hot that they could not be boarded. The Main and Bremen had foundered on the Weehawken Flats. They were half sunk, burned out, and heeled-over partially on their sides. At 11:00 P.M. that night - an amazing discovery was made when it was found that 15 crewmen were still alive in the Hull of the Main. Even with her hull plates glowing from the heat, a tug captain noticed a small oil lamp was shining from the side of the ship. Upon investigating the tug's crew heard knocking from within, and the plates were soon cut into to reveal the men. They had been hiding in an empty coalbunker, and by the time they were freed they had been trapped in the bunker for eight hours. They had jammed their clothes in crevices to keep from suffocating from the smoke. One man had been able to stick his burned arm through a porthole to signal with the oil lamp. The Saale had sustained the most damage. Her paint had peeled in many places due to the extreme heat of the blaze. She was the only one of the ships not to be returned to service with the Lloyd. The Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse had been docked at Cunard's Pier 52 since she was due to sail on Tuesday, July third. She left fully occupied and with an addition of 400 crewmembers from Saale, Main, and Bremen. As the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was on her way out of the harbor, she passed by the burned-out hulk of the Saale where divers were searching for bodies. The fire was the largest fire loss in the U.S. for that year. Insurance estimates for the damage were calculated at $4,627,00. Four liners burned, three seriously damaged, 27 barges, workboats, and harbor craft were lost. On land the losses were great as well: warehouses, railroad cars, the three North German Lloyd piers and one pier of the Thingvalla Line were totally lost. The pilings of the Lloyd piers looked like tombstones sticking up out of the water and smoke. They were burned down to the water level, bulkhead houses and everything. The Hoboken fire department had fought hard to save the piers - one fire wagon virtually disintegrated when it first arrived at the scene and was immediately engulfed by flames, the firemen luckily escaping. A total of 173 people had died on the piers with 100 of them being buried in a mass grave at Flower Hill Cemetery in North Bergen, New Jersey. Most of the others who died in the fire were buried there as well and also at other cemeteries in the area. The upkeep of the mass grave at Flower Hill Cemetery is maintained by the current incarnation of the North German Lloyd and the Hamburg America Line, Hapag-Lloyd, to this day. Here is an abstract from the New York Times about the largest funeral held for the victims: "Police captain Hayes, with a detail of men, marched at the head of the procession. Directly behind him came the band of the Kaiser Wilhelm II., escorting a number of stewards from that steamer, carrying numerous large floral pieces which had been contributed by comrades of the dead. Chief of Police Donovan, Mayor Fagen, the German Vice Consul, and representatives of the North German Lloyd followed in carriages. The Seaman's Benefit Society and the Longshoreman's Union were followed by eleven hearses. Capts. Peterman of the Main and Nierrich of the Bremen followed in carriages. After them marched twenty survivors of the Saale, headed by First Officer Schaeffer and Second Officer Zander. The bands of the Barbarossa and Trave* headed delegations of officers and sailors bearing more floral offerings. Nine hearses and the five catafalques followed. The rear was brought up by about one hundred carriages containing those who had lost relatives in the fire. The funeral procession moved along First Street to River Street, passing the scene of the disaster, thence through Third Street to Washington Street, and from there to Fourteenth Street, where it disbanded. Those on foot returning and the carriages following the bodies to Flower Hill Cemetery, where a long row of graves awaited the bodies. At the cemetery the Rev. Dr. William R. Jenvey, Archdeacon of Jersey City, read the Episcopal burial service, assisted by Rev. George S. Bennitt of Grace Protestant Episcopal Church, Jersey City." *Barbarossa and Trave were steamers of the North German Lloyd that arrived after the fire had dissipated. The picture above shows one of the Piers, which burned, possibly Pier 1. The salvage firm of Merritt Chapman Wrecking Co. was enlisted to salvage the Main, Bremen, and Saale. It took a few months to pump the water out of the ships and to re-float them. The Bremen was the first to be repaired enough so that she could return to Germany. She was given temporary repairs in New York and then went to Philadelphia to pick up a load of cotton to take to Bremerhaven, where she was given a major overhaul. The Main was worse off and had to be towed to Newport News, Virginia, to be repaired by the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry-dock Co. She then returned to service with the North German Lloyd. The Saale was sold in January 1901 to the Luckenbach S.S. Company where she was rebuilt as a freighter and was renamed three times before being scrapped in 1924. In the aftermath of the fire, dynamite was used in an attempt to free bodies thought to still be in the wreckage of the ruined pier structures and the Campbell's Stores Warehouses. The odor from the decaying bodies was noticeable, and the corpses themselves would have presented a health problem to the city. Now, the North German Lloyd piers were to be completely rebuilt, using many new fire-prevention techniques, concrete and steel. The new piers that were built were even longer and more spacious to support the newest and largest ships that would be coming from Germany in the future, and were totally completed by 1906. Until the new piers were finished though, the Lloyd used a temporary pier rented from Cunard, Pier 52. Two other piers in Brooklyn were rented and converted for passenger service, and sometimes piers at the neighboring Hamburg America Line, or the French and White Star lines in Manhattan were used. The final number of those dead cannot be totally estimated, but they numbered from 326 to 400. Please read some of the other sources that are listed in the Bibliography section of this website. There are many more interesting, brave, and terrible accounts that are documented in those sources. I am indebted to them and to the Hoboken Public Library for what I have learned about this subject. Thank you for making it this far, my writing is far from perfect, but I hope that you at least got something out of all this. It is a subject that is not often talked about, and was only mentioned a few times on the 100th anniversary of the fire in June and July of 2000. This picture shows the former North German Lloyd Pier area at Hoboken, July 5th, 2001. Casualties This is a list of the dead and missing as stated in issues of the New York Times, published from July 1st to July 4th, 1900. It must be remembered that this list will never be accurate due to the record-keeping systems then in use and the chaos that is always present during a disaster. For example, some of the people listed as missing may not necessarily have died, as some were known to have deserted their stations and simply just went somewhere else while the fire ensued. Many of the members of the ship's crews resided in Hoboken or the surrounding area, and unlike those members of the crew that lived in Bremerhaven Germany for example, had no need to stay. They simply went off to find new work or left for whatever reason. So when the surviving officers tried to account for their crews over the next few days, they could not find them all and so they were thus listed as "missing". I read one account that said one of the missing was later seen walking around Brooklyn. Of course, many had indeed died from the fires or were drowned. They would never be accounted for. The New York Times collected these lists from area morgues and also from independent reports made by people that sometimes found the victims floating by the water's edge at Jersey City, further away at Brooklyn, or at other surrounding areas of New York City. I would like to thank those who sent emails to me suggesting doing this; it was a very fitting idea. Please note that I have typed many of the details verbatim from the reports of the New York Times. Some of the content below contains very graphic descriptions of some of the unknown victims. Out of respect for those victims whose names were known, I would never list any information of that sort about them. From the Steamer "Saale" Addens, Georg, on Saale. Albert. Anna, on Saale. Alester, Edward, on Saale. Ammermann, Carl, on Saale. Armgarth, Arthur, on Saale. Baars, Wilhelm, on Saale. Barghahn, Johann, on Saale. Baron, Alfred, on Saale. Barre, August, age 36, butcher on Saale. Barrona, Alfred, third officer on Saale. Bartholomaus, F... [truncated due to length]