Collections Item Detail

Article (re Edward J. Florio): A Racketeer Takes Over an American City. By Jules Weinberg. Look, July 17, 1951; Log Cabin ad.

2012.042.0001

2012.042

Anonymous

Gift

Anonymous gift.

1951 - 1951

Date(s) Created: 1951 Date(s): 1951

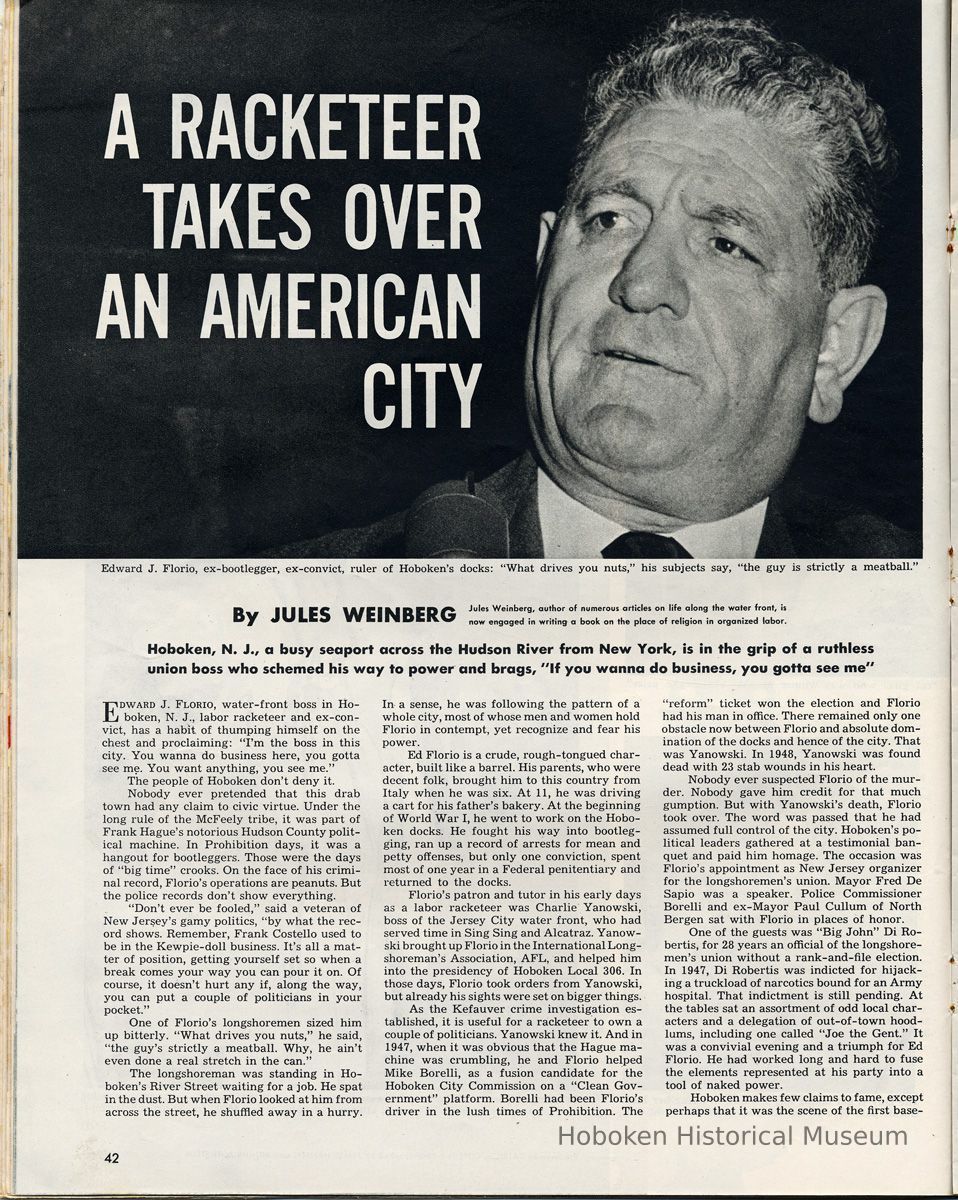

Notes: 2012.042.0001 Look magazine, July 17, 1951, Volume 15, Number 15, pages 43-[43]: A RACKETEER TAKES OVER AN AMERICAN CITY [caption below photo portrait of Florio] Edward J. Florio, ex-bootlegger, ex-convict, ruler of Hoboken's docks: "What drives you nuts," his subjects say, "the guy is strictly a meatball." By Jules Weinberg. Jules Weinberg, author of numerous articles on life along the water front, is engaged in writing a book on the place of religion in organized labor. Hoboken, N. J., a busy seaport across the Hudson River from New York, is in the grip of a ruthless union boss who schemed his way to power and brags, "If you wanna do business, you gotta see me" Edward J. Florio, water-front boss in Hoboken, N. J., labor racketeer and ex-convict, has a habit of thumping himself on the chest and proclaiming: "I'm the boss in this city. You wanna do business here, you gotta see me. You want anything, you see me." The people of Hoboken don't deny it. Nobody ever pretended that this drab town had any claim to civic virtue. Under the long rule of the McFeely tribe, it was part of Frank Hague's notorious Hudson County political machine. In Prohibition days, it was a hangout for bootleggers. Those were the days of "big time" crooks. On the face of his criminal record, Florio's operations are peanuts. But the police records don't show everything. "Don't ever be fooled," said a veteran of New Jersey's gamy politics, "by what the record shows. Remember, Frank Costello used to be in the Kewpie-doll business. It's all a matter of position, getting yourself set so when a break comes your way you can pour it on. Of course, it doesn't hurt any if, along the way, you can put a couple of politicians in your pocket." One of Florio's longshoremen sized him up bitterly. "What drives you nuts," he said, "the guy's strictly a meatball. Why, he ain't even done a real stretch in the can." The longshoreman was standing in Hoboken's River Street waiting for a job. He spat in the dust. But when Florio looked at him from across the street, he shuffled away in a hurry. In a sense, he was following the pattern of a whole city, most of whose men and women hold Florio in contempt, yet recognize and fear his power. Ed Florio is a crude, rough-tongued character, built like a barrel. His parents, who were decent folk, brought him to this country from Italy when he was six. At 11, he was driving a cart for his father's bakery. At the beginning of World War I, he went to work on the Hoboken docks. He fought his way into bootlegging, ran up a record of arrests for mean and petty offenses, but only one conviction, spent most of one year in a Federal penitentiary and returned to the docks. Florio's patron and tutor in his early days as a labor racketeer was Charlie Yanowski, boss of the Jersey City water front, who had served time in Sing Sing and Alcatraz. Yanowski brought up Florio in the International Longshoreman's Association, AFL, and helped him into the presidency of Hoboken Local 306. In those days, Florio took orders from Yanowski, but already his sights were set on bigger things. As the Kefauver crime investigation established, it is useful for a racketeer to own a couple of politicians. Yanowski knew it. And in 1947, when it was obvious that the Hague machine was crumbling, he and Florio helped Mike Borelli, as a fusion candidate for the Hoboken City Commission on a "Clean Government" platform. Borelli had been Florio's driver in the lush times of Prohibition. The whole city, most of whose men and women hold Florio in contempt, yet recognize and fear his power. Ed Florio is a crude, rough-tongued character, built like a barrel. His parents, who were decent folk, brought him to this country from Italy when he was six. At 11, he was driving a cart for his father's bakery. At the beginning of World War I, he went to work on the Hoboken docks. He fought his way into bootlegging, ran up a record of arrests for mean and petty offenses, but only one conviction, spent most of one year in a Federal penitentiary and returned to the docks. Florio's patron and tutor in his early days as a labor racketeer was Charlie Yanowski, boss of the Jersey City water front, who had served time in Sing Sing and Alcatraz. Yanowski brought up Florio in the International Longshoreman's Association, AFL, and helped him into the presidency of Hoboken Local 306. In those days, Florio took orders from Yanowski, but already his sights were set on bigger things. As the Kefauver crime investigation established, it is useful for a racketeer to own a couple of politicians. Yanowski knew it. And in 1947, when it was obvious that the Hague machine was crumbling, he and Florio helped Mike Borelli, as a fusion candidate for the Hoboken City Commission on a "Clean Government" platform. Borelli had been Florio's driver in the lush times of Prohibition. The "reform" ticket won the election and Florio had his man in office. There remained only one obstacle now between Florio and absolute domination of the docks and hence of the city. That was Yanowski. In 1948, Yanowski was found dead with 23 stab wounds in his heart. Nobody ever suspected Florio of the murder. Nobody gave him credit for that much gumption. But with Yanowski's death, Florio took over. The word was passed that he had assumed full control of the city. Hoboken's political leaders gathered at a testimonial banquet and paid him homage. The occasion was Florio's appointment as New Jersey organizer for the longshoremen's union. Mayor Fred De Sapio was a speaker. Police Commissioner Borelli and ex-Mayor Paul Cullum of North Bergen sat with Florio in places of honor. One of the guests was "Big John" Di Robertis, for 28 years an official of the longshoremen's union without a rank-and-file election. In 1947, Di Robertis was indicted for hijacking a truckload of narcotics bound for an Army hospital. That indictment is still pending. At the tables sat an assortment of odd local characters and a delegation of out-of-town hoodlums, including one called "Joe the Gent." It was a convivial evening and a triumph for Ed Florio. He had worked long and hard to fuse the elements represented at his party into a tool of naked power. Hoboken makes few claims to fame, except perhaps that it was the scene of the first baseball game between organized teams. But its place in the national economy is fixed by the fact that it is an integral part of the Port of New York. The port's docks, rigidly controlled by the ILA, are one of the nation's worst crime centers. The take runs high. Aside from smuggled narcotics, alcohol and aliens, and murder-for-profit, the bill for pilferage alone runs to $100,000,000 a year. Thousands of men who 4 do the heavy labor of longshoremen are at the mercy of the racketeers who control their ^ means of livelihood. With his elevation to control in Hoboken, Florio's power worked both ways: He had political protection in his racketeering and he could return favors by reason of his waterfront control. On one hand, Borelli's political support got Florio the job as New Jersey organizer; on the other hand, Florio could dictate the granting of patronage plums. Slavery, Water-Front Style Any morning of the week after he achieved high union office, as Florio took his stand on River Street he could watch the men gathering at the pier gates. Not one of them could claim a full-time job as a longshoreman. There is no such thing. A hiring boss appears at the gate and blows a whistle. The men hurry to form about him in a semicircle—the shape-up, as it is called. By merely pointing a finger at a man, the hiring boss gives him work, not for a week or a day but for four hours at a time. Tuesday is considered the first day of the week. A man who works that day receives a ( numbered brass check which is his receipt for whatever work he is given. He is supposed to retain it, no matter how much or how little work he gets, until payday. But by that time 4 many of the men no longer have their checks. They have sold them at 10 per cent discount to Tony Aurigemma, a loan-shark union official. Often 500 men will shape up for 100 jobs. The unchosen drift into the water-front bars, idle until the next call. Some of these men are bonafide union members. Many are not. It is common practice to buy union books from union officials. Whether the fees they pay are entered in the books is questionable, for there are always more men holding books than those listed in the union records. In one year, throughout the entire Port of New York, more than 40,000 "union members" drew pay checks. But the ILA accounts showed payment of per capita tax on only 17,000. There is another class of drifters, or "chenangos," who get by on union buttons. The buttons cost union officials a few cents, but they're sold to the chenangos for $5 to $10. The "Short-Gang" Racket None of these shady performances could continue without the knowledge and at least tacit consent of Ed Florio. The Florian touch is evident also in the barefaced practice that is called "short-ganging." The contract with the pier owners calls for a minimum of 22 in each working gang, and four to seven gangs are used to load or unload each ship. But when the hiring boss works the short-gang racket, he takes on only 16 or 17 men instead of the legal 22 and makes up the difference by falsifying the records. The loot runs to thousands of dollars a week. Florio's personal take includes the revenue from a loading partnership with Joe Branda. Loaders are paid about five cents a hundred weight for loading and unloading trucks on the piers. Florio and Branda employ nine or ten men and the firm nets $1800 to place in the national economy is fixed by the fact that it is an integral part of the Port of New York. The port's docks, rigidly controlled by the ILA, are one of the nation's worst crime centers. The take runs high. Aside from smuggled narcotics, alcohol and aliens, and murder-for-profit, the bill for pilferage alone runs to $100,000,000 a year. Thousands of men who 4 do the heavy labor of longshoremen are at the mercy of the racketeers who control their ^ means of livelihood. With his elevation to control in Hoboken, Florio's power worked both ways: He had political protection in his racketeering and he could return favors by reason of his waterfront control. On one hand, Borelli's political support got Florio the job as New Jersey organizer; on the other hand, Florio could dictate the granting of patronage plums. Slavery, Water-Front Style Any morning of the week after he achieved high union office, as Florio took his stand on River Street he could watch the men gathering at the pier gates. Not one of them could claim a full-time job as a longshoreman. There is no such thing. A hiring boss appears at the gate and blows a whistle. The men hurry to form about him in a semicircle—the shape-up, as it is called. By merely pointing a finger at a man, the hiring boss gives him work, not for a week or a day but for four hours at a time. Tuesday is considered the first day of the week. A man who works that day receives a numbered brass check which is his receipt for whatever work he is given. He is supposed to retain it, no matter how much or how little work he gets, until payday. But by that time 4 many of the men no longer have their checks. They have sold them at 10 per cent discount to Tony Aurigemma, a loan-shark union official. Often 500 men will shape up for 100 jobs. The unchosen drift into the water-front bars, idle until the next call. Some of these men are bonafide union members. Many are not. It is common practice to buy union books from union officials. Whether the fees they pay are entered in the books is questionable, for there are always more men holding books than those listed in the union records. In one year, throughout the entire Port of New York, more than 40,000 "union members" drew pay checks. But the ILA accounts showed payment of per capita tax on only 17,000. There is another class of drifters, or "chenangos," who get by on union buttons. The buttons cost union officials a few cents, but they're sold to the chenangos for $5 to $10. The "Short-Gang" Racket None of these shady performances could continue without the knowledge and at least tacit consent of Ed Florio. The Florian touch is evident also in the barefaced practice that is called "short-ganging." The contract with the pier owners calls for a minimum of 22 in t each working gang, and four to seven gangs are used to load or unload each ship. But when the hiring boss works the short-gang racket, he takes on only 16 or 17 men instead of the legal 22 and makes up the difference by falsifying the records. The loot runs to thousands of dollars a week. Florio's personal take includes the revenue from a loading partnership with Joe Branda. Loaders are paid about five cents a hundred weight for loading and unloading trucks on the piers. Florio and Branda employ nine or ten men and the firm nets $1800 to $2500 a month. Each of the men, including several of Florio's relatives, is supposed to get an equal share of the income. But Florio and Branda take a 10 per cent cut for themselves. There is also a nice dodge to finance the "contributions" Florio makes to politicians and their enterprises. These usually take the form of buying tickets to political functions. First, the amount of the contribution—$100 to $500 or more—is skimmed off the top of the firm's weekly income, thus reducing each man's share of the total. Then the tickets are sold to the men, who thus are kicked in the teeth twice. The withholding-tax racket is another source of gravy. Each week, when the loaders gather for the split-up, Joe Branda, who makes up the payroll, tells each man how much he has deducted for income tax, social-security payments and other insurance. But when the year-end tax statements are distributed, they show not only that less money was entered on the books than was actually earned, but also that less money was turned over to the Government than was "withheld" from pay. One man earned $4000 in a year, yet his withholding-tax statement made out by the firm showed earnings of $500. His withholding payments had totaled $700, yet his statement showed payments of only $75. If he had wanted to pay his legal tax, he would have had to make up the difference himself. He tackled Florio about it but got the brush-off. "That's the way we work here," Florio said. "You want to keep your job?" The longshoremen have tried legitimate action to get rid of Florio. They petitioned their international chairman for an election but they were turned down. Last August, 6000 of them struck. Florio kept a handful of his pensioners at work and strode among the sullen strikers, his bodyguards beside him—a curious figure of a union leader breaking a strike. As the strike continued, a notorious killer, who recently was returned to prison for violation of parole, came over from New York to see Florio. They stood in River Street. The killer looked at his watch. It was 2: 30 p.m. He gave Florio half an hour "to get your rats off." Florio's bodyguard faded. His men came off the piers. But the killer was called away on other business and Florio hollered for help from Police Commissioner Borelli. Platoons of police showed up and the strike was broken. Rumors circulated about Florio's business operations outside the union. The Kefauver committee went into such matters but did not dig deeply enough to hurt Florio. One evening last summer, Florio left his club, the Company K, having offered to drop off a friend. The two got into Florio's car and stopped at the friend's destination. Another car pulled in behind them. Two men sprang from it and dragged the frightened Florio from the driver's seat. Florio's companion tried to intervene and got a slam in the mouth with a taped lead pipe. He ran. Florio, taking advantage of the diversion, broke away, but his pursuers caught him and slugged him to the pavement. He got up and screamed: "For God's sake, don't kill me." Two storekeepers came to his rescue and Florio ran. He was overtaken and beaten down again. Blood ran down his face. "St. Anthony, save me," he screamed, "St. Anthony . . ." A motorcycle roared in the near distance, and Florio's assailants sauntered away, probably thinking the police were coming. It turned out to be a joy-rider. Florio crawled across the street toward the Borelli Democratic Club just as the Police Commissioner came out. Borelli helped Florio into the clubhouse. A moment later, two bystanders saw Mayor De Sapio, Judge De Fazio, Deputy Police Commissioner Failla and Police Sergeant Ricciardi leave the club in a hurry. Such incidents give men ideas. The Stolen Grenades At about that time, ten Army hand grenades were stolen from a Hoboken pier. One ripped open a union office in Jersey City where some of Florio's men were accustomed to meet. Another burst in the car of a union official. Florio did not appear to be intimidated. In a recent city election in Hoboken, his candidates won control again. Florio, at this time of writing, may be on his way to the Company K Club as usual. The party will be under way, its guests all big wheels in the machinery of criminal activity and twilight politics that is essential to up-to-date racketeering. How long the party will go on is open to question. With the power of the docks behind him, Florio has the pocketbook appeal to keep it going. But there was one murder on the Hoboken docks this spring and, as a New York newspaper man commented, there are still eight grenades to be accounted for. END [caption for photo bottom right page 43] Longshoremen scatter as "shape-up" breaks. For jobs on the docks, many are called, few are chosen. (photo is looking east at the Holland America Line Fifth Street Pier.) Status: OK Status By: dw Status Date: 2012-09-19

![pg [43]](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/8a5151e0-fa7b-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdhWNg.tn.jpg)

![detail photo pg [43]: Fifth Street Pier; Holland America Line](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/8b83b760-fa7b-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdhWhM.tn.jpg)

![pg [61] Log Cabin Syrup advertisement](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/8cb42110-fa7b-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFdhXJk.tn.jpg)