Article: Where the North Sea Meets North River: Quaint and Quiet as a Holland Village is This Street in Hoboken. Robert M. Coates; NYT, March 28, 1928.

2014.002.0033

2014.002

Staff / Collected by

Collected by Staff

Museum Collections.

1928 - 1928

Date(s) Created: 1928 Date(s): 1928

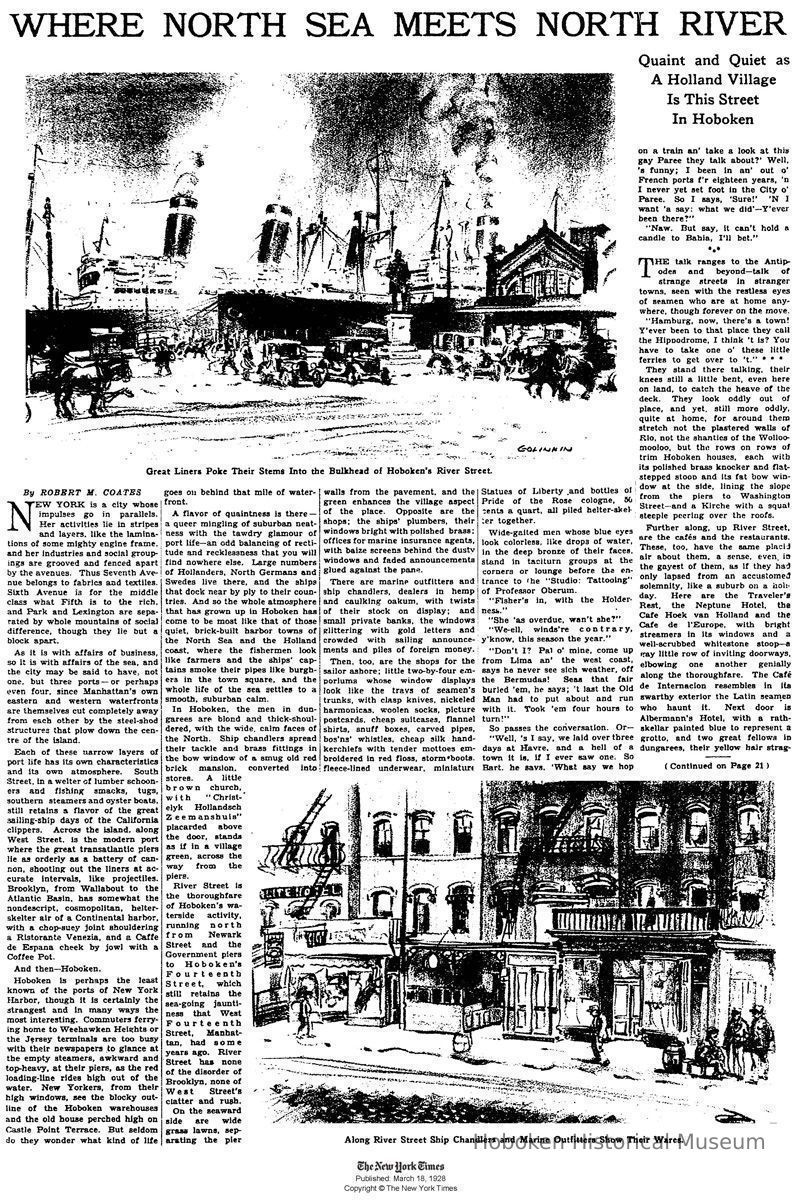

Notes: The New York Times, March 28, 1928. ==== [page 14] WHERE NORTH SEA MEETS NORTH RIVER: Quaint and Quiet as A Holland Village Is This Street In Hoboken. [illustration, drawing] Great Liners Poke Their Stems Into the Bulkhead of Hoboken’s River Street. (signed: Golinkin) By ROBERT M. COATES NEW YORK is a city whose impulses go in parallels. Her activities lie in stripes and layers, like the laminations of some mighty engine frame, and her industries and social groupings are grooved and fenced apart by the avenues. Thus Seventh Avenue belongs to fabrics and textiles. Sixth Avenue is for the middle class what Fifth is to the rich, and Park and Lexington are separated by whole mountains of social difference, though they lie but a block apart. As it is with affairs of business, so it is with affairs of the sea, and the city may be said to have, not one. but three ports — or perhaps even four, since Manhattan’s own eastern and western waterfronts are themselves cut completely away from each other by the steel-shod structures that plow down the centre of the island. Each of these narrow layers of port life has its own characteristics and its own atmosphere. South Street, in a welter of lumber schooners and fishing smacks, tugs, southern steamers and oyster boats, still retains a flavor of the great sailing-ship days of the California clippers. Across the island, along West Street, the modern port where the great transatlantic piers lie as orderly as a battery of cannon, shooting out the liners at accurate intervals, like projectiles. Brooklyn, from Wallabout to the Atlantic Basin, has somewhat the nondescript, cosmopolitan, helter-skelter air of a Continental harbor, with a chop-suey joint shouldering a Rlstorante Venezia, and a Caffe de Espana cheek by jowl with a Coffee Pot. And then—Hoboken. Hoboken Is perhaps the least known of the ports of New York Harbor, though It Is certainly the strangest and in many ways the most interesting. Commuters ferrying home to Weehawken Heights or the Jersey terminals are too busy with their newspapers to glance at the empty steamers, awkward and top-heavy, at their piers, as the red loading-line rides high out of the water. New Yorkers, from their high windows, see the blocky outline of the Hoboken warehouses and the old house perched high on Castle Point Terrace. But seldom do they wonder what kind of life ---- goes on behind that mile of waterfront. A flavor of quaintness Is there — a queer mingling of suburban neatness with the tawdry glamour of port life—an odd balancing of rectitude and recklessness that you will find nowhere else. Large numbers of Hollanders, North Germans and Swedes live there, and the ships that dock near by ply to their countries. And so the whole atmosphere that has grown up in Hoboken has come to be most like that of those quiet, brick-built harbor towns of the North Sea and the Holland coast, where the fishermen look like farmers and the ships’ captains smoke their pipes like burghers in the town square, and the whole life of the sea settles to a smooth, suburban calm. In Hoboken, the men in dungarees are blond and thick-shouldered, with the wide, calm faces of the North. Ship chandlers spread their tackle and brass fittings in the bow window of a smug old red brick mansion, converted into stores. A little brown church, with "Christelyk Hollandsch Zeemanshuis” [Christian Home for Holland Seamen and Immigrants] placarded above the door, stands as if in a village green, across the way from the piers. River Street is the thoroughfare of Hoboken's waterside activity, running north from Newark Street and the Government piers to Hoboken’s Fourteenth Street, which still retains the sea-going jauntiness that West Fourteenth Street, Manhattan, had some years ago. River Street has none of the disorder of Brooklyn, none of West Street's clatter and rush. On the seaward side are wide grass lawns, separating the pier ---- walls from the pavement, and the green enhances the village aspect of the place. Opposite are the shops; the ships’ plumbers, their windows bright with polished brass; offices for marine insurance agents, with baize screens behind the dusty windows and faded announcements glued against the pane. There are marine outfitters and ship chandlers, dealers in hemp and caulking oakum, with twists of their stock on display; and small private banks, the windows glittering with gold letters and crowded with sailing announcements and piles of foreign money. Then, too, are the shops for the sailor ashore; little two-by-four emporiums whose window displays look like the trays of seamen's trunks, with clasp knives, nickeled harmonicas, woolen socks, picture postcards, cheap suitcases, flannel shirts, snuff boxes, carved pipes, bos’ns’ whistles, cheap silk handkerchiefs with tender mottoes embroidered in red floss, storm'boots. fleece-lined underwear, miniature ---- Statues of Liberty and bottles of Pride of the Rose cologne, 50 cents a quart, all piled helter-skelter together. Wide-galted men whose blue eyes look colorless, like drops of water, In the deep bronze of their faces, stand in taciturn groups at the corners or lounge before the entrance to the ‘‘Studio: Tattooing" of Professor Oberum. "Fisher’s in, with the Hoiderness.” “She ‘as overdue, wan’t she?” “We-ell, winds’re contrary, y’know, this season the year.” "Don’t I? Pal o’ mine, come up from Lima an’ the west coast, says he never see sich weather, off the Bermudas! Seas that fair burled ’em, he says; ’t last the Old Man had to put about and run with it. Took ’em four hours to turn!” So passes the conversation. Or— “Well, ’s I say, we laid over three days at Havre, and a hell of a town it is if I ever saw one. So Bart, he says. ’What say we hop ---- on a train an’ take a look at thin gay Paree they talk about?’ Well, 'a funny; I been in an’ out o’ French ports f’r eighteen years, ’n I never yet set foot in the City o’ Paree. So I says, ‘Sure!’ ’N I want ’a say: what we did’—Y’ever been there?" "Naw. Rut say, it can’t hold a candle to Bahia, I’ll bet.’’ *** The talk ranges to the Antipodes and beyond—talk of strange streets in stranger towns, seen with the restless eyes of seamen who are at home anywhere, though forever on the move. "Hamburg, now, there’s a town! Y’ever been to that place they call the Hippodrome, I think ’t is? You have to take one o’ these little ferries to get over to ’t.” They stand there talking, their knees still a little bent, even here on land, to catch the heave of the deck. They look oddly out of place, and yet. still more oddly, quite at home, for around them stretch not the plastered walls of Rio, not the shanties of the Wolloo-mooloo, but the rows on rows of trim Hoboken houses, each with its polished brass knocker and flat-stepped stoop and its fat bow window at the side, lining the slope from the piers to Washington Street—and a Kirche with a squal steeple peering over the roofs. Further along, up River Street, are the cafes and the restaurants. These, too, have the same placid air about them, a sense, even, in the gayest of them, as If they had only lapsed from an accustomed solemnity, like a suburb on a holiday. Here are the Traveler's Rest, the Neptune Hotel, the Cafe Hoek van Holland and the Cafe de l'Europe, with blight streamers in Its windows and a well-scrubbed whltestone stoop—a fray little row of inviting doorways, elbowing one another genially along the thoroughfare. The Cafe de Internacion resembles in its swarthy exterior the Latin seamen who haunt it. Next door is Albermann’s Hotel, with a rathskellar painted blue to represent a grotto, and two great fellows in dungarees, their yellow hair strag- (Continued on Page 21) ---- [illustration, drawing] Along River Street Ship Chandlers and Marine Outfitters Show Their Wares. ==== [page 21] NORTH SEA AND NORTH RIVER ( Continued from Page 14 ) gling from under fatigue caps, deciding between wienerschnitzel and sauerbraten and blutwurst, on the bill of fare. These are not, be it understood, the dives and "chain-lockers" that make ports infamous. Usually the house is set back from the sidewalk and the space between is arbored over and set with tables, so that In warm weather the place suggests the Old World rather than the New. and men sitting there with glass and sandwich may well fancy, as they stare across the quiet street at the grass-grown docks and the steamers lazily unloading, that they are at home again in one of their toylike villages of the Lowlands. And if, now and then, one can find an innkeeper who dispenses beer a little better than the legal limit — well, that only seems to help the illusion! There is little of the disorder and irregularity usual in port life. Entering the cafes, you will find a brisk, trim Interior, sometimes with the owner's wife helping to serve the customers. In the Ryndam Cafe among many others, the scrubbed tone prevails. A man stands at the window screen, looking out at a liner dropping down to the bay. Three others lean on the bar, sipping their beer with the profound, unmedltative calm oi seamen at rest. Harry, the owner, stands at the taps, eternally polishing glasses. Harry has been a seaman, too, and the walls are hung with his mementos—pictures of great liners going full blast through raging blizzards, depicted in ail the tints that color printing can be guilty of; and oil paintings in real oils, as amateurish as the others are mechanical, of harbor views and sunset views and full-rlgged ships at sea. Pinned among these are postcards of Samoa and Punta Arenas, Callao and Cadiz, portraits of Harry when, for a brief time, he played the accordeon in the halls, and “art" likenesses of near-nude ladies, bought on the Grand Rue at Marseilles. Harry has the severe face and the gentle manners of the Northerner; when he talks, w's tend to become v’s. and d's soften into t’s, and the r’s roll on his tongue. Once in a while, somebody strolls back to put a nickel in the piano; tables are pushed away and the seamen dance solemnly two by two, ---- pathetically, in the absence of women. There is never any rowing or brawling in Harry’s place. Harry has a Hollander's calm and also a fair share of the native thrift. Harry—he once confided in me—has a purpose in life. "Now. listen; I tell you,” he said. "This is all right. I got my place; I make money, all right. But joost now is good times. Come bad times, I got to be careful. Here is all right. The boys come, they drinks a little, they laugh, they enjoy themselfs. But If there comes trouble—wow! The police; they shut me up. They charge me fines. No. I tell you.” He leans across the bar in his earnestness. “I tell you what my idea is. Two, three, maybe four years we have goot times. Then come bad times, an' you won't see no more Harry.” He laughs with a contented chuckle. “Four years I make $20.000. I save. An' you know what I do? You see me back in Holland. For $20,000 I buy me a boat—a goot boat, with a motor and a cabin and all. And I live on dose boat. On a boat you pay nc rent. I live on dose canals in Holland • • •” He pauses. "That’s all I want. All my life.’’ No wonder Harry's place is quiet and orderly. *** As with Harry, so with all the others, patrons and proprietors alike, seamen and shipowners. German and Hollander and Norseman. they poke their blond heads in at many doors, their light-shrunk eyes peer in at many a port. But wherever they go, their blood tells them that the green-shaded, white-walled towns of the North arc best. And somehow, by the very active power of their memories perhaps, they have made the little Port of Hoboken more like home to them than any other. How long it may remain so is another question. Back of this little zone of suburban quiet is the City of Hoboken, and back of that the Greater City, and back of that the whole United States, with all our traditions of efficiency and speed and maximum production. And so, recently. Investigations j have been set afoot. Experts have been studying the harborage. Grand Juries have held hearings and Issued reports, stating ominously that "the number of ships docked” was only "75 per cent of what the piers could utilize” and detailing the attendant loss thus suffered by merchants, landlords and taxpayers along the business streets and manufacturing districts that surround the port. They blame the Shipping Board, which holds many of the piers. A bill has been prepared for introduction in Congress embodying the effort to lift Hoboken port out of Its present calm. Perhaps all this will have its effect, for the American method is a mighty one, and the needs of industry are Inexorable. But it will be strange, and a little sad. to see that Sunday quiet violated. The little houses along River Street will come down, for, though quaint, they are certainly not very remunerative to the owners. The grass plots will give way to warehouses. And, what with cranes and derricks and locomotives, nothing much will be left of Hoboken's little suburb of the sea. ==== ==== Status: OK Status By: dw Status Date: 2014-10-29