Collections Item Detail

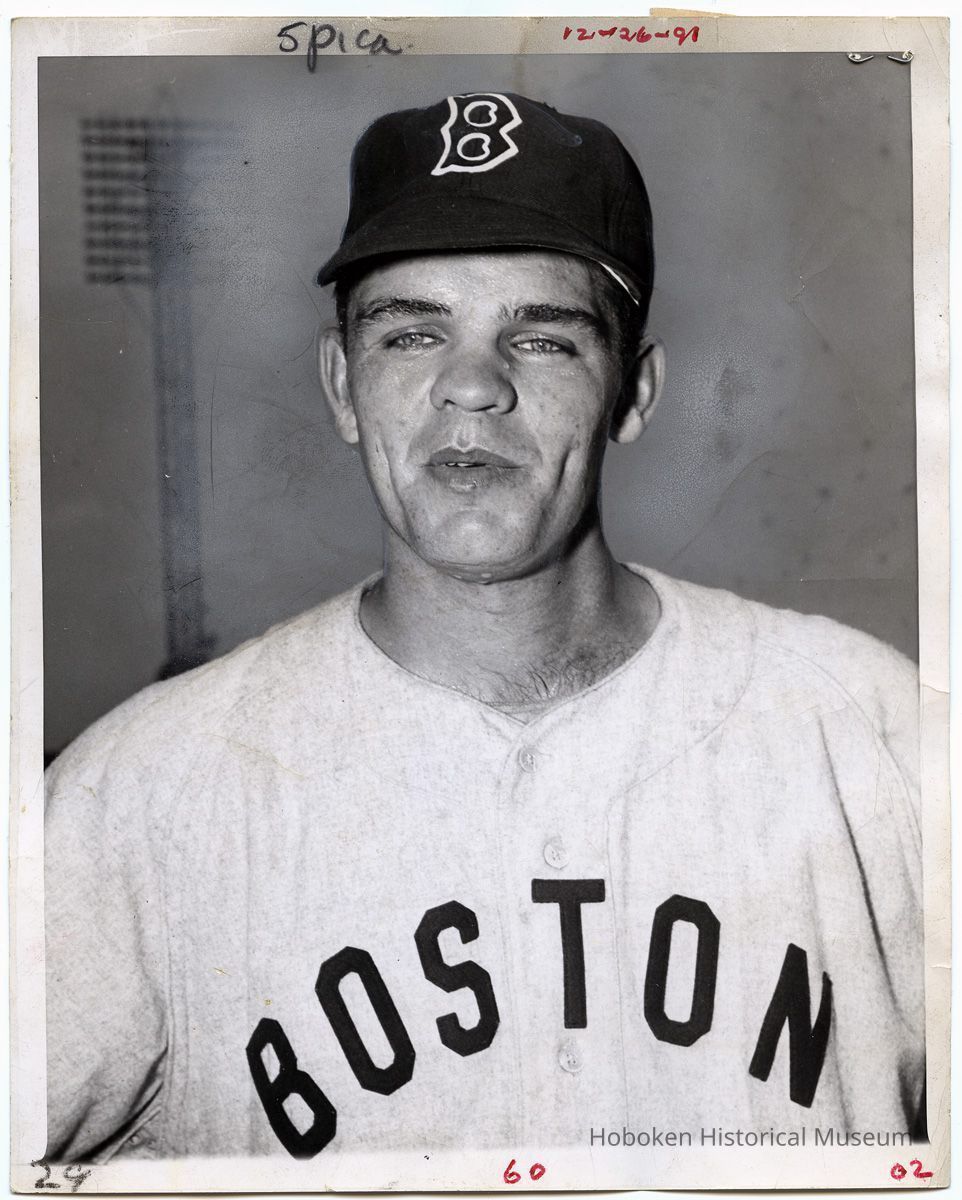

B+W photo of Hoboken native Leo Kiely in Boston Red Sox baseball uniform, n.p., n.d., ca. 1954-1959

2014.019.0001

2014.019

Amabile, Anthony A.

Gift

Gift of Anthony A. Amabile.

Associated Press

1954 - 1959

n/a

Date: 1954-1959

8 in

10 in

Fair

Notes: Photo 2014.019.0001 Biographical entries for Leo Kiely from two internet resources: Wikipedia Society for American Baseball Research ==== Wikipedia 2014 URL: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leo_Kiely Leo Kiely Pitcher Born: November 30, 1929 Hoboken, New Jersey Died: January 18, 1984 (aged 54) Montclair, New Jersey Batted: Left Threw: Left MLB debut: June 27, 1951 for the Boston Red Sox Last MLB appearance: June 20, 1960 for the Kansas City Athletics Career statistics Win-Loss Record 26-27 Strikeouts 212 ERA 3.37 Teams Boston Red Sox (1951, 1954–59) Mainichi Orions (1953) Kansas City Athletics (1960) Leo Patrick Kiely (November 30, 1929 – January 18, 1984) was an American pitcher in Major League Baseball who played between 1951 and 1960 for the Boston Red Sox (1951, 1954–56, 1958–59) and Kansas City Athletics (1960). Listed at 6 feet 2 inches (1.88 m), 180 pounds (82 kg), Kiely batted and threw left-handed. He was born in Hoboken, New Jersey. Kiely entered the majors in the 1951 midseason with the Red Sox. He finished with a 7–7 record and a 3.34 ERA in 16 starts before joining the military during Korean War. In 1953, he pitched for the Mainichi Orions of the Pacific League to become the first major leaguer to play in Japanese baseball, while going 6–0 with a 1.80 ERA for Mainichi. He returned to Boston in 1954. After beginning in long relief, he ended up as a set-up man for closers Ellis Kinder (1955) and Ike Delock (1956). In 1957 Kiely was demoted to Triple-A. He finished with a 21–6 record and a 2.22 ERA for the PCL San Francisco Seals, leading the league in wins. 20 of them came in relief, including 14 in consecutive games, to set two PCL records. The 1958 TSN Guide also credited Kiely with 11 saves during the 14-game winning streak. Kiely led the Red Sox with 12 saves in 1958, while going 5–2 with a 3.00 ERA in 47 relief appearances. He also pitched with the Athletics in 1960, his last major league season. In a seven-season career, Kiely posted a 26–27 record with a 3.37 ERA in 209 games, including 39 starts, eight complete games, one shutout, 29 saves, and 523.0 innings of work. He went 63–36 during his minor league career. Kiely died in Montclair, New Jersey at age 54. ==== ==== Entry for Kiely at website of Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) 2014 URL: http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bf43e126 SABR Baseball Biography Project Leo Kiely This article was written by Greg Erion. Many major leaguers are more remembered for their accomplishments in the minors. Ron Necciai’s 27 strikeouts in a minor-league game outshone his lackluster performance with the Pittsburgh Pirates. Ox Eckhardt’s lifetime minor-league average of .367 overshadowed two brief trials in the majors. And Leo Kiely’s achievement of winning 20 games in relief during a season while with the San Francisco Seals in the Pacific Coast League stands in sharp contrast to a middling career with the Boston Red Sox and Kansas City Athletics. Leo Patrick Kiely, born on November 30, 1929, in Hoboken, New Jersey, was the son of Leo P. and Marie Kiely. His father, as was typical of many Irish Americans assimilating into society during this era, was employed in the public sector, serving in the Hoboken Fire Department, where he reached the rank of captain. Leo’s grandfather was a police inspector. Young Leo was the second of four children; his sister, Eileen, was the oldest, and there were two younger brothers, Daniel and Robert.1 Young Leo’s childhood was not without difficulty. At the age of 5 he was run over by a truck. The accident broke his kneecaps and fractured his pelvic bone; for a time there was question whether he would walk again. While he recovered, the accident left him with a slight limp and a left leg half an inch shorter than the right, requiring that he wear a built-up shoe.2 Kiely, who never attended high school, joined the CYO League and under the guidance of Father Francis X. Coyle of Our Lady of Grace Church showed talent for baseball. He was signed by Boston Red Sox scout Bill McCarren in 1948.3 Kiely had been approached by the Dodgers but felt Boston provided better opportunity. That he was a left-hander -- always a premium at Fenway Park -- was added consideration. Father Coyle also gave young Kiely a nickname, the first of many, calling him Blackie. During an era when players were often nicknamed, Kiely developed more than his share. He came to be known as KiKi, Le-Ki, and Black Cat. The later sprang from a habit Kiely developed of taking a toy black cat to the bullpen with him during games.4 Kiely started with the Wellsville (New York) Nitros in the Class D PONY League in 1948. He fashioned a solid 12-9 record and a team-leading 3.40 earned-run average. The next year he was promoted to the Scranton (Pennsylvania) Red Sox of the Class A Eastern League. Illness interrupted his season and he finished with a lackluster 3-5 record. Despite this setback, in 1950 Kiely was promoted to the Double-A Birmingham Barons in the Southern Association, where he had a breakout year. Pitching for manager Mike Higgins, the 20-year-old Kiely finished fourth in the league in victories with an 18-9 performance. This record earned a call to spring training with the Red Sox in 1951 before he was assigned to the Louisville Colonels in the Triple-A American Association, now managed by Higgins. While Kiely worked through the minors, Boston was a perennial challenger, often coming close to, but never winning, the pennant. In early 1951, they were again in the chase. By late June, despite a few holes in their lineup, they were third behind the surprising Chicago White Sox and the New York Yankees. Hoping to improve, Boston decided to shake up its roster. Walt Dropo, Rookie of the Year in 1950 but now mired in a slump, was optioned to the San Diego Padres in the Pacific Coast League. And as The Sporting News article carrying details of Dropo’s demotion and other Boston roster shuffles, noted, “A left-handed pitcher, Leo Kiely, also was brought up at the same time.”5 Kiely’s debut, on June 27, was made in a non-pitching role. Red Sox starter Ray Scarborough singled against the Philadelphia A’s in the third inning and was struck in the head by an errant pickoff throw. Scarborough was taken out of the game and replaced by Kiely as a pinch-runner. Kiely made his first pitching appearance on July 2, against the Washington Senators. Although the Senators were in seventh place, Kiely faced solid players, including Irv Noren, Sam Mele, Mickey Vernon, and Eddie Yost. But Kiely displayed “a veteran’s poise” as the Hartford Courant put it, scattering 10 hits, without any walks, in a complete-game 5-2 victory. The win kept the Red Sox 3½ games behind the Yankees.6 Kiely’s next start came 10 days later against the league-leading White Sox. He lasted into the seventh inning with a 3-2 lead before being relieved in a game that went 17 innings.7 Next he pitched against the Cleveland Indians, a reflection of Boston’s confidence in matching him against the league’s best teams (the Indians finished second to the New York Yankees that season). Kiely pitched into the fifth inning with a 3-0 lead before a line drive by Larry Doby struck his knee and forced him out of the game.8 That play had an unintended consequence. Kiely’s mother, watching him on television for the first time, was convinced she had brought him bad luck. She would never again watch a game he pitched.9 By now Kiely was impressing all with his performance; “cool poise under fire” was how Red Sox manager Steve O’Neill characterized his pitching.10 At this point, outside forces intervened to affect his career. The Korean War was at its height in 1951, and just as World War II affected major-league baseball so did the “police action” in Korea. When Kiely was summoned by his draft board for a physical examination, there was hope that his childhood accident might allow deferment, but he was classified 3-C, making him eligible to serve in a noncombat situation.11 He was to report for induction in the Army after the season ended. More than 50 major-league players were eventually drafted during the Korean War era. Boston was particularly hit hard, losing four players to military service, including Kiely and Ted Williams (who was recalled to the service by the Marines). Despite the looming interruption to his career, Kiely pitched well the next several weeks. He defeated the first-place Yankees, 4-2, on September 5. Over the following 11 days he beat both the Tigers and White Sox, bringing Boston within 2½ games of the lead on September 16. Although it could not have been foreseen at the time, Kiely’s victory over the White Sox was the high point of his career as a starter. And Boston was not in contention this late in the season until their pennant-winning effort in 1967. After the 16th, Boston went 2-12 the rest of the way and finished a distant third as injuries forcing the retirement of second baseman Bobby Doerr and reducing the effectiveness of shortstop Vern Stephens blunted their attack. Kiely’s performance also suffered; he took three losses in the final two weeks. For the season, Kiely posted a 7-7 record with a 3.34 earned-run average, a performance that reflected well on him. Kiely’s style of pitching was consistent throughout his career. Of slender build (listed at 6-feet-2 and 180 pounds) and lacking great speed, he had to rely on location and guile. Boo Ferriss, a teammate and later the Red Sox pitching coach, recalled Kiely’s best pitch, a sinker that induced ground balls.12 Bill Monbouquette’s analysis of Kiely’s game later in his career contained the same observation of a very effective sinker.13 The season over, Kiely was inducted into the Army and was assigned to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. Just before he entered the Army, his engagement to Marilyn Dunne of Jersey City was announced.14 Hoping to keep his skills sharp, Kiely pitched numerous exhibition games including several for various veterans benefit events. Later, while in Japan, he estimated that he won “either 16 or 17 games and only lost one.”15 Kiely’s efforts to keep himself in shape met with many challenges. One of his former and future teammates, Frank Sullivan, met him outside Tokyo toward the end of 1952 and recalled one specific “trial” Kiely faced. As Sullivan told it: “I was in a group of guys walking back to our barracks and saw a really fat body with Leo’s head on it leading a group of soldiers marching down the street. I kept looking and as they got abreast I said, ‘Hey! Is that you, Leo?’ ‘Yeah, who wants to know?’ He halted his troops, looked over and said, ‘Hey, Sully! How the hell are you?’ ‘None of your business,’ I replied, ‘and how the hell you get so fat?’ ‘The rice beer is blowing me up.’ We both laughed and hugged and stood there talking until his troops started grumbling. ‘See you back in the real world, Sully. We’ll play some ball and have some real beer.’ ”16 Toward the end of his tour of duty, Kiely had an opportunity to pitch in Japanese professional baseball. Various publications and web sites credit both Kiely and Phil Paine with being the first players with major-league experience to play in the Japanese pro leagues, both during the latter part of the 1953 season. Based on available records, Kiely appears to have been the first, making his debut on August 8, 1953. Paine’s initial appearance came on August 23.17 Kiely pitched six games for the Mainichi Orions, winning each while posting a 1.80 ERA. Pitching on days off from his Army duties, he was reportedly paid 100,000 yen per month, only 10,000 yen less than the Japanese prime minister got. Upon his discharge, Kiely was asked about his overseas experiences. He referred only to his pitching against other Army teams, never mentioning his time with Mainichi. This omission reflected Americans’ prevalent lack of regard for Japanese professional baseball.18 Kiely’s return to Boston was eagerly awaited. The Sporting News reflected this anticipation. He was described as “the left-handed pitcher who was beginning to look like a solid 20-game winner when the Army grabbed him.”19 Lou Boudreau, the Red Sox manager, chimed in: “The pitcher I’m most anxious about is Kiely. He’s back with us after two years in the Army. He was a great prospect when he left and they tell me he did a lot of good pitching in the Army.”20 That Kiely’s worth was high was confirmed when rumors surfaced that he was being considered as trade bait for reigning American League batting champ Mickey Vernon.21 While Kiely was preparing for his return to the majors, he attended to a matter of personal importance. Marilyn Dunne, whom Leo met through his elder sister Eileen,22 flew to Sarasota, Florida, where the Red Sox were training, and on March 18, 1954, they were married.23 On the eve of Opening Day, Kiely signaled that he was ready to go. “I may not be quite as fast as when I went into the service, but I think I know a lot more about pitching,” he said. “The big idea is that I have more confidence. I’m more mature and I’ve worked hard this spring to get ready with a lot of help from everybody in camp.”24 If Kiely felt he was ready to resume his career with smooth sailing, he was rudely disabused of this notion during his first appearance of the season. Pitching at Yankee Stadium on April 21, he was roughed up for four runs in six innings. His second pitch of the game signaled what was to come that season: Gil McDougald homered in the eventual 11-8 Red Sox loss. The next several starts were not much better. By the middle of June, Kiely was 1-5. On July 4, he threw the sole shutout of his major-league career when he blanked the Philadelphia A’s, 8-0. Five days later, despite being knocked out of the box in the fifth, he found time to hit his only major-league home run, a solo shot off Philadelphia’s Alex Kellner at Connie Mack Stadium. Later that month, he followed a complete-game, four-hit victory against the White Sox with a complete-game win in Cleveland, one of only two games Boston won in their 22 meetings with the pennant-winning Indians that season. Successes were sporadic. Kiely attributed his lack of success to his time in the service, saying, “I think I forgot a little about pitching while I was in the Army.”25 As the season progressed, Kiely was used more frequently in relief and showed effectiveness in that role. For the season, he ended with a disappointing 5-8 record. A close examination, however, indicated exceptional ability in relief. Of the 28 games he appeared in, nine were as a reliever. In these games his ERA was a superlative 0.97. Boston finished 42 games behind Cleveland and the finish cost Boudreau his job. He was replaced by Mike Higgins, who had managed Kiely in the minors. Higgins was aware of Kiely’s potential but felt he had picked up bad habits while overseas. Higgins said he and pitching coach Boo Ferriss would work with Kiely to get him back to top form.26 Noting Kiely’s performance in relief, he said he was considering Kiely as a replacement for ace reliever Ellis Kinder, who at the age of 39 had come off a subpar season. Kiely proved a solid part of the 1955 bullpen. He, Kinder, and Tom Hurd were credited with helping make Boston a serious contender. Kiely made four starts and pitched well, but had settled into his relief role. The last start of his career came against the White Sox in late July. The Red Sox faded late in the season and finished fourth. In 1956, the Red Sox again finished fourth although they never seriously contended. The bullpen’s decline hampered their performance. Both Hurd and Kiely proved major disappointments. Kiely lost his form and became ineffective, reflected in his 5.17 ERA over just 31? innings. With the emergence of Ike Delock as a reliable closer and Kiely’s continued poor outings, on July 31, he was optioned to the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League. For Boston, which had purchased the Seals in late 1955, the 1956 season proved disappointing as the Red Sox both overestimated the quality of players it placed on the Seals and underestimated the quality of PCL play. The Seals were mired in sixth when Kiely arrived. They had just fired Eddie Joost as manager, replacing him with Joe Gordon. Kiely arrived virtually unnoticed. He appeared in 13 games, all in relief, compiling a 1-2 record with a 2.10 ERA. Kiely was invited to the Red Sox camp in the spring of 1957; however, his contract was soon sold outright to the Seals, his departure hastened when he got on Higgins’ wrong side.27 As if that were not bad enough, Kiely took his time joining the Seals, which angered Gordon. Former Phillies closer Jim Konstanty, trying to make a comeback at the age of 40, was penciled in to handle the relief pitching.28 The Seals had improved over the winter. Frank Kellert, late of the Chicago Cubs, and Bill Renna, formerly of the Yankees and Athletics, were added to the roster. Each drove in over 100 runs for the Seals. With the exception of second baseman Ken Aspromonte and outfielder Marty Keough, the entire starting lineup changed from 1956. Outfielder Albie Pearson, who had joined the Seals late the previous season, was available from the start.29 The Seals’ pitching staff was rebuilt: The lone mound holdovers from the previous season who would last through this season were Bill Abernathie, Bob “Riverboat” Smith, and Kiely. Kiely began the season in the bullpen, although over the next several weeks Gordon used him both to start and relieve games. But he found Kiely inconsistent as a starter and effective in relief. After losing a start against the San Diego Padres late in May, Kiely was used exclusively in the bullpen. By this point he was 6-2, with five of the wins in relief. Kiely’s appearances reflected how relief pitchers were typically used at that time -- they were brought into the game when it was on the line. Kiely could be called on as early as the third or fourth inning, or as late as the ninth. This often allowed him to win games he did not start. The Seals were competitive early on and took the league lead for good in early June. Between June 4 and June 16, Kiely won three games and saved one to cement the Seals’ lead. By now, Boston had taken notice and speculation grew that he might be recalled. Ultimately it was decided to leave him with the Seals, no doubt to ensure a first-place finish.30 By the beginning of July, Kiely was 11-2, with a perfect 10-0 record in relief. Part of that streak included back-to-back wins over the Los Angeles Angels on June 26 and 27, the latter win achieved on Kiely’s two-run double in the ninth. Kiely eventually picked up 14 relief wins in a row before giving up the lead in the ninth inning of a game against the Seattle Rainiers in late July. This loss placed him at 15-3, with 11 “saves,” then a loosely-construed term used to describe situations where a lead, under threat, was held. The “save” statistic would not officially come into vogue until 1960.31 The loss proved a mere hiccup for Kiely. Two days later, in relief of Bert Thiel, Kiely gained his 16th win of the season against Vancouver. What caused Kiely’s turnaround? In conversations with manager Gordon and catcher Haywood Sullivan, Kiely was told “to let up a little … and by golly, that’s all he needed to get them out.” Kiely concurred. If he let up on the ball it would give his sinker a chance to work. “The harder I threw, the less effective I was. When I let up on the ball, they started beating it into the ground.”32 This change in his delivery not only sharpened his “out” pitch, it gave him great control. Kiely’s two main pitches, a sinker and a dipping fastball, caused observers to note, “A good 75 percent of the balls hit off him are on the ground. This gets him a lot of double plays when he comes in from the bullpen with ducks on the pond.”33 Kiely recognized that his frame did not lend itself to throwing nine innings. “I’m better just going three or four innings, I don’t weigh enough to go nine. I tire,” He said. An asset to working out of the bullpen was an unusual ability to warm up quickly. Ten or 12 pitches and he was ready to go.”34 Joe Gordon said, “The way he gets the ball over is remarkable. We haven’t had a nine-inning pitcher to our name since the first month of the season, and with Leo’s control I’ve got to have him in the bullpen. One thing I’m sure of when I put him in there is he’s not going to walk anyone.” Kiely ended the season with only 24 walks in 146 innings. Bill Renna, a teammate on the Seals and later in Boston, recalled, “He wasn’t a hard-throwing left-hander – but he had good breaking pitches and excellent off-speed pitches.”35 Bert Thiel remembered Kiely as one of the best control pitchers he ever saw. 36 Becoming the ace of a pennant-winning team did not change Kiely’s temperament. His wife’s description of him as a quiet man off the field was consistent with his demeanor in the clubhouse.37 Bob DiPietro described him as someone “laid back, who lived to play baseball and drink beer.”38 Duane Pillette echoed DiPietro’s observation of Kiely as a quiet man, a gentleman, and one who unhesitatingly took the ball when called upon.39 Kiely had another characteristic noted by many. Frank Sullivan, a keen observer of his surroundings, described Kiely’s penchant for beer: “He was one of the all-time beer drinkers. Never loud, never out of hand, he could sit quietly and drink you into oblivion. I continually marveled at the way he would pour each bottle of beer slowly and deliberately into a small glass and savor each sip as if it were the first of the day. I believe he was made up of 98% liquid. After five warm-up pitches he would literally be dripping sweat from the bill of his cap. His personality was as even-keeled as anyone I had ever met; he had absolutely no enemies. I counted him as one of my best pals on the team. Leo was one of the sweetest guys I ever met. There wasn't a bad bone in his skinny body.”40 The Sporting News noticed that Kiely had the rare opportunity to win 20 games in relief. On September 7, 1957, he was called upon to relieve at San Diego. With the score tied 2-2, Kiely threw three innings of one-hit ball. The Seals scored four runs in the top of the 10th and Kiely retired the side in the bottom of the inning to record his 20th win, his 19th in relief. The next day, Kiely was called on to relieve in the fifth. He held San Diego to earn his 21st win of the year, his 20th in relief. Kiely’s achievement of 20 wins in relief was rare. Hy Hurwitz, writing in The Sporting News after the season ended, wrote, “I don’t believe anyone else in the majors or high minors ever had a pitcher who was a 20-game winner as a reliever.”41 Elroy Face of the Pittsburgh Pirates won 18 games as a reliever in1959. No other major-league reliever has topped that mark. While minor-league records over the years are incomplete, a review of available data indicates that only one other reliever in professional baseball won 20 games in one season. That achievement also occurred in 1957. On August 11, Don Nichols won his 20th game of the season in relief for the Peoria Chiefs in the Class B Three-I League. A career minor-league pitcher, Nichols won 22 games in relief that season. The Seals ended the season 3½ games ahead of Vancouver. Kiely finished 21-6 with a 2.22 ERA. His 21 victories led the Pacific Coast League. His performance was recognized by his selection to the PCL All-Star team and in being named runner-up to the Los Angeles Angels’ Steve Bilko as the league’s Most Valuable Player. More tangibly, Boston recalled Kiely for the next season. The Red Sox had finished third in 1957. Higgins said in the offseason, “We’d have done better last year if we’d had a reliable southpaw. We didn’t. But we’ve got hopes that this situation will be corrected for the coming season. Leo Kiely will be back after a great year in San Francisco. Anybody who wins 20 games in any league must be outstanding.”42 Despite adulation over his performance and his promotion, Kiely was under no illusions about the challenge before him. “I know that if I fail this time I’ve had it,” he said.43 To ensure success, Kiely worked as a longshoreman on the New Jersey docks during the offseason to stay in shape.44 He became Boston’s ace reliever for the 1958 season, finishing 5-2 with 12 saves, third in the league. But the next season, he was inconsistent, finishing with a 4.20 ERA. In January 1960, Kiely was traded to the Cleveland Indians for infielder Ray Webster. The trade puzzled Red Sox-watchers. Bill Lee, writing in the Hartford Courant, could not understand why Kiely had been given away for so little. If the trade was of little importance to Boston, it was well considered by Cleveland. Kiely was acquired at the behest of Joe Gordon, now managing the Indians. Gordon, reunited with his Seals ace, praised Kiely as spring training began: “He throws nothing but ground balls. All Kiely needs in plenty of work. That keeps him sharp.” 45 Whether Kiely would have helped Cleveland in 1960 became moot when he was traded two months later to the Kansas City Athletics for pitcher Bob Grim. Kiely joined a team that had finished seventh for three years running. A’s general manager Parke Carroll said Kiely was acquired as a “one- and two-inning reliever. … He has good stuff and he can get it over.”46 One bright spot for the last-place 1960 Athletics was Kiely’s pitching. As the A’s top reliever, he had seven consecutive scoreless games to begin the season; after giving up a run, he reeled off five more scoreless appearances. On June 20, Kiely made an appearance against Boston. It was the first time he faced his former teammates. While he gave up several hits, enabling Boston to tie the game, he struck out Ted Williams. An out and two hits later Kiely was removed from the game. It was his last game in the majors. Within a few days Kiely was placed on the disabled list with a sore arm. Subsequently he was operated on for bone chips in his elbow and the procedure seemed to go well.47 Kiely did not return for the season and planned on coming back the next year. He had pitched very well for the A’s. Appearing in 20 games, Kiely posted a 1.74 earned run average. During the winter, Kiely was placed on the major-league draft list. There were no takers. Kiely came to Kansas City’s spring camp seemingly recovered from his operation. Joe Gordon now managed the A’s. Once again, a reunion not to be. Kiely could not demonstrate that he had regained his effectiveness, and he was released on March 5, 1961. The release, before spring games were started, was timed to allow him to catch on with another team. As with the earlier winter draft, there was no interest.48 Leaving baseball, Kiely eventually moved to Arlington, New Jersey, with his wife and son, Leo. He worked as a mechanic for a gas station, as a car dealer, and finally for the Finkle Trucking Company in Clifton, New Jersey. Kiely retained a love of the game and enjoyed regaling one and all with stories of his experiences. His nieces still recall anecdotes of clubhouse brawls, nights in New York with the likes of Whitey Ford and Jackie Gleason, as well as cold summer ballgames in San Francisco. Kiely retired in 1974. A heavy smoker, he developed throat cancer, and died on January 18, 1984, at the age of 54. The disease had earlier claimed his father and other members of his family.49 His wife, Marilyn, survived him, and as of 2009 was still living quietly in New Jersey. His son, Leo, died in 2005. Kiely had finished his major-league career with a 26-27 record with an excellent 3.37 ERA in 523 innings. Although he did not compile a distinguished record, he played in the majors for seven seasons. His outstanding season with the Seals in 1957 remains one of the most remarkable records compiled in the high minors. Statistics aside, former teammates in the majors or minors spoke highly of him. Quiet, reserved, he was well liked. Frank Sullivan captured it best: “If I could come back to earth after death, one of the things I would try and do again is join Leo in our everyday ritual in spring training the moment the daily workout ended which rarely went past noon. We went over to the Mid Night Fishing Pass docks on Siesta Key in Sarasota and claimed our outstanding order of two hot sandwiches, two dozen live shrimp in the live well of our rental boat already loaded with a case of iced-up Budweiser. Leo will always be a friend of mine.”50 Notes 1 Robin Mehrer supplied data on the Kiely family in 2009. 2 “Aching Back Kiely’s Only Drawback,” Washington Post, September 8, 1951: 11 3 Ibid. 4 Rich Marazzi and Len Fiorito, Baseball Players of the 1950s (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2004), 188. 5 “Stunned Dropo Sent to San Diego, Hopes to ‘Hit Hell Out of Ball,’” The Sporting News, July 4, 1951: 5. 6 “Rookie Wins First Start For Red Sox,” Hartford Courant, July 3, 1951: 11. 7 “Twin Win over Chicago,” Los Angeles Times, July 13, 1951: C1. 8 “Steve Pitcher-Rich, Along Comes Kiely to Make Him Richer,” The Sporting News, August 1, 1951: 9. 9 Michele Kiely-Cramer, telephone interview, December 14, 2009. 10 “Problem in Stretch Half of Season to Split Work Among Red Sox Starters and Relievers,” The Sporting News, August 1, 1951: 9. 11 “Leo Kiely, Bosox Hurler, Assigned to Camp Kilmer,” Hartford Courant, October 18, 1951:13; “Frosh Ace, Leo Kiely, Lost to Army,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1951: 16. 12 E-mail from Boo Ferriss on October 22, 2009. 13 Bill Monbouquette, letter, October 16, 2009. 14 “Kiely of Red Sox Going Into Army,” Christian S... [truncated due to length]