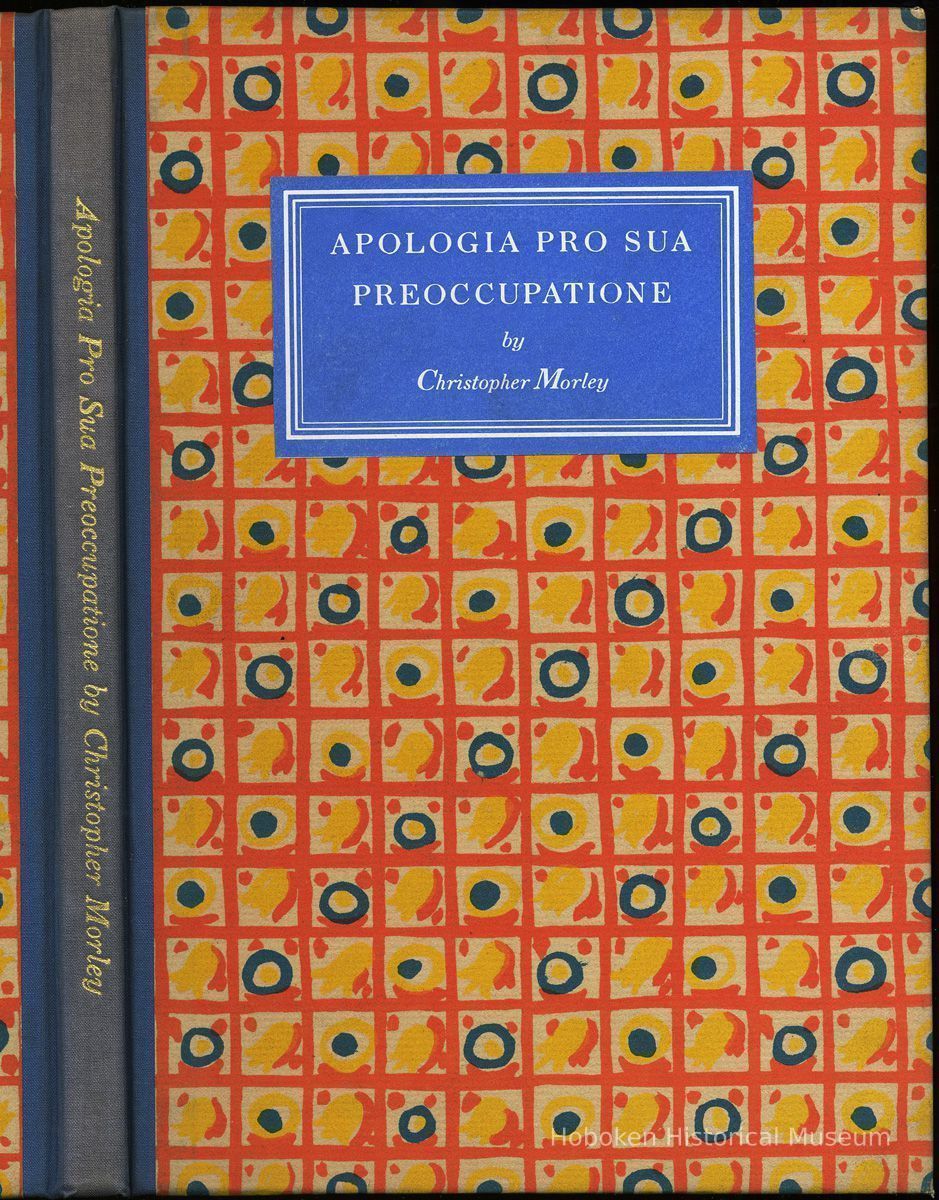

Apologia Pro Sua Preoccupatione

2012.001.0113

2012.001

Purchase

Purchase

Museum Collections.

Morley, Christopher

1st in book form; limited edition; signed

Foundry Press

New York

1930

Notes: "Apologia Pro Sua Preoccupatione" by Christopher Morley in The Saturday Review of Literature, January 18, 1930, p. 653 (concluding on page 655.) "A Little Back Room" by Christopher Morley in The Saturday Review of Literature, December 28, 1929, p. 603 Full text of volume: APOLOGIA PRO SUA PREOCCUPATIONE by [autograph signature] Christopher Morley M C M X X X THE FOUNDRY PRESS: R. C. RIMINGTON at No. 1 West 67th Street, New York ==== [verso title] Copyright, 1930 THE FOUNDRY PRESS: R. C. RIMINGTON Printed in the United States of America ==== [chapter or section title] Apologia Pro Sua Preoccupatione ==== [page 5] 1 WHAT is there in the damned old place that makes me love her so, beyond reason or sense? Is it her incorrigible shabbiness? There's a queer eddy of wind on Hudson Street, which so operates that all the jetsam of the highway is drawn in some airy suction to twirl and nestle on our front pavement. A lively scour of breeze, from whatever quarter, funnels itself into a vacuum ==== beside our steps: all the papers, loose trash, cabbage leaves, disjected rubbish, deposit humorously in the path of the arriving patron. I used to imagine this some deliberate jocularity of neighbors until I studied the meteorology of Hoboken. There is actually a spiral of atmosphere that gathers every casual leaf of paper on Hudson Street and spins it to our door. It avails not how often our burly and diligent McBride goes out with his broom. The explorer from Manhattan, delicately choosing his way, doubtless smiles a little to read the legend "America's Most Famous Theatre" blazoned on so proletarian a facade. (By the way, Mac, those front door panes need washing.) What is it indeed that makes us love her? Is it 6 ==== the queer diversity of her fortunes? She began life as a beer-garden; she has played burlesque and vaudeville and movies; she has known every vicissitude; and the certainties too, both death and taxes. There is a scrubwomen's cupboard upstairs, formerly used to store mops and pails and aprons; we turned it into our little business office; there is just room for a manager, a typewriter, one of those skewers you spear bills on, and a telephone conversation with prospective customers. On the wall of that humble closet are some historic numerals scrawled in pencil. They date from the days when Marty Johnson was manager and playing burlicue, 14 performances a week. The figures record the house's old High Water Mark for weekly Take. Marty remembers that it was the 7 ==== Stone and Pillard burlesque company that hung up that record. I shan't quote the digits, but we nearly doubled them once during the run of After Dark. --- "My Old Lady, London," cries Eddie Newton [cataloguer's note: noted book collector A. Edward Newton] in his tender and charming tributes to the world's greatest town. In somewhat the same spirit I give you my mistress, that jocund and preposterous old theatre. The Old Rialto, she's toasted! (Mac, be sure to keep a good draught going in the furnace these cold days. But an Old Rialto audience's feet are the warmest anywhere, because they mark time to the songs on the uncarpeted floor. Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, the boys are marching. . . .) There must have been some subtle and instinc- 8 ==== tive affinity between us, for from the time Throck first showed her to me I have had no other god but her. I have endured plentiful reproach on her behalf: the warnings of friends,the groans of old kin-sprits . When are you going to get back to your writing, they say—as if sitting in a room and writing were life complete. Well, there's plenty to write about; but in the joy and annoyance and perplexity of the theatre there is something that moves deeper than mere writing (which, as an exclusive occupation, is a lonely and morbid job.) I see that wistful mystery of the theatre peeping out sometimes in the casual remarks of such champion old showmen as Mr. Belasco—in whom the stage is not just an exhilarating gamble but (as the famous collar would seem to imply) a form of naive 9 ==== theology. In the miracle of the theatre you see a form of art in actual impact upon its ultimate consumer. Faulty, clumsy, imperfect as your intuitions may be, you see (and feel) an intangible and radiant thing struggling for communication. Occasionally you see that same thing at the mercy of an audience insensitive to its conventions. The old melodramas, for instance, which afford the audience so many heart-easing opportunities for collaboration, also tacitly assume that those who "assist" (admirable French word for the spectators ) do not chime in at the wrong moment, simply because by doing so they lose the niceties which are necessary to their complete pleasure. So long as the things one loves are worth fighting for, so long it is worth the labor, day after day, to return 10 ==== to the hazardous and hopeful task. Raising a play is as patient and continuous a job as raising a child. And though there are times when one is too proud to speak for things one loves, there are also times perhaps when one must be too proud to be silent. ---- I sat down after a certain performance to let my mind move over some meanings and memories that the Old Rialto has for me. It was the kind of performance that means perhaps most of all: a post-holiday matinee when the house was meagre, when the Public showed its large and inalienable capacity for Staying Away. (What a genius for Not Coming the public can sometimes have, every showman knows.) And by one of those happy chances it proved one of the finest performances 11 ==== I have seen anywhere. The company gave their best: one had the divine pleasure of seeing some of them actually achieve what one had known was latent but had not quite come through before in the way of feeling and (as directors love to say) "projection." The audience, at first frightened by its own smallness (people have always a delicious instinct of inferiority when they find themselves fewer than they expect) then warmed into genuine and affectionate enthusiasm. Sincerity on the stage came across the footlights and created real union. Old and poor and unfashionable as the theatre was that afternoon, by God I was proud of her; and I said to myself that even the humblest of her lovers might speak out for her. For such moments men live, when they see their fellows 12 ==== giving all they have, without assurance of gain or glory. And I felt honorably sorry for those who were not there, for they had missed something beautiful and merry. --- How many extraordinary memories of companionship in mirth or anxiety the show business affords. I know something of the problems of the author; even, if I must be candid, of the trouper; but for the close pressure of reality I bespeak your sympathy for the "Front of the House" and the Manager, that seldom romanticized figure. I look back upon some notably unsuccessful ventures at another theatre, and I perceive how enormously important it is in this Divine Comedy to learn how to Take a Licking. Perhaps you have 13 ==== never stood in the box office of a dying show, when there is plenty of time to smoke and meditate between customers, and considered how charmingly pretty the tickets are, piled up in the rack for Advance Sales. White, yellow, fawn, green, pink, red, lilac—such attractive colors and all equally unsalable. Yes, to have lived through some of those afternoons is a necessary part of one's education in Show Business. I can still hear Tom muttering to himself over the checkbook as he figured out how Saturday afternoon was to be met; hear the depressing thump as Kathryn rubber-stamped a thick wad of tickets to be given away to paper the house, marking them as "duckets." (Or should it be "ducats"? I rather suspect that that term for free tickets is as old as Shakespeare. 14 ==== Many a manager, at such times, has echoed old Shylock's cry of anguish—"Thou stick'st a dagger in me: four-score ducats at a sitting!" Perhaps that was even a little showman joke that Shakespeare put in to amuse himself.) What delightful flurries of hopefulness—the promptness with which one answers the tiny buzz of the telephone. (Box office phones do not ring, they purr softly in a confidential annunciator.) I hear Tom saying: "When an agency orders eleven tickets on you it ain't a bad sign." Nor shall I forget the time when a tall powerful person appeared at the window and I was all ready to assure him that I could give him two in the tenth, yes, and right on the aisle. He hesitated, seemed singularly anxious to speak as intimately and discreetly as 15 ==== possible, and finally, inserting a large and mobile mouth right into the round aperture in the glass, remarked "I represent the Sheriff." Fortunately, just across the street from the Lyric stage door there was an excellent lunch-wagon, where one could (and can) get a very filling meal for about twenty-five cents. There is no old trouper anywhere who does not look back with affection on many such interludes. --- Perhaps our costly experience at the Lyric made us love the Old Rialto all the more. There is an air of unbelievableness about her that still persists even when we know her so well. She is so gorgeously unaesthetic! When the house was built they quite forgot to put in any dressing- 16 ==== rooms, which had to be supplied afterward in a lean-to addition leased from the adjoining property. They are approached through a tunnel under the theatre, a stony old passage-way as romantically satisfying as any crypt in Westminster Abbey. To our great pleasure this dressing-room wing has a legal easement upon it permitting the maintenance of clothes-masts, from which the linen of Hudson Street flutters bravely over the rear alley. It is that alley which serves as Green Room on summer evenings. Nothing could be pleasanter than to see the company taking their ease out there on benches in the warm nights last summer; and Old Tom, the crapulous sandwich man in After Dark, whose rags nothing could further tarnish, stretched on the cobbles. Good beer 17 ==== is not far to seek. May I make a managerial confession? I was substituting in the role of Old Tom while Arthur Morris was on vacation. During that week there was a member of the company who missed a critical cue at matinee by dallying overlong with the clam broth cup in our favorite clam brothel. I was much outraged by this breach of professional rigor, and prepared a Notice for him which I was going to hand him that evening. That very night, so is human frailty chastised, I committed the same error myself, in the same tavern. I destroyed that Notice undelivered. There were a few minutes in the second act of After Dark while Old Tom waited offstage in his boat, before Eliza jumped off the dock. It was then that they sang "The Little Old Log Cabin 18 ==== in the Lane," and the substitute Old Tom used to lie there, gazing up at a border of blue lights overhead and speculating on the complete improbability of the whole affair. I suppose it is the intimate sense of companionship in effort which is part of the theatre's magic. You surrender much of the complete egotistic control which a writer has over his own job; in return you receive the curious joys and pangs inseparable from a parliamentary affair proceeding by chancy human compromise. And the collaborated efforts of the theatre, however arduous, are by necessity undertaken in a social spirit more intensely grotesque and emotional than any other work can suggest. It is a commonplace of experience that sometimes in rehearsals you attain ef- 19 ==== fects you never touch again. In that elastic, casual, farcical and nerve-strained period, marked by endless hours, irregular meals, weariness, despair, cauldrons of midnight coffee and screams of laughter, certain vibrations of human comedy are most strongly plucked. Particularly, I admit, in our Hoboken rehearsals, many of which have always been held in haphazard places. Most of the rehearsing of The Blue and The Gray was done in the parlor of the Continental Hotel; it used to be special fun to see Joe Samperi, the hospitable little proprietor, gravely watching in a corner ; the success of the play meant as much to him as to us. I often wondered what his guests may have thought, when they came into the lobby to register and heard the outcry of Northerners and 20 ==== Confederates practising their romantic bitterness in the parlor. And the mythical Philadelphian of the old postman story, if he dropped into Bill's grillroom across the back alley one of these evenings, would surely be disturbed to see officers in correct C.S.A. uniform lined up at the bar for that hot clam broth and liverwurst. --- Any theatre, anywhere, is always an appeal to the imagination; but very specially, in this death-day of the oldtimers, a house that has had so long and checkered a career. A place like that arouses loyalties that sound almost too sentimental for offhand print. I do not forget how little Eleanor, then our box-office cashier, used to call me up at home in the evenings when After Dark was be- 21 ==== ginning to go over the top. One night she said "It's over six hundred, isn't it wonderful!" There was a pause, and I heard a queer gargling sound. "Excuse me, Mr. Morley," she continued, "but I couldn't help it. I'm crying." Nor do I forget how Mildred stood by in the box office in the bitterly cold weeks when After Dark had closed and the house was lifeless until we got The Blue and The Gray ready. The furnace was not on, and in spite of electric heaters arranged in a formidable battery we could not keep Mildred's extremities warm. But she sat on a stool, on a pile of telephone books, and pattered away on a typewriter; and anyone who called Hoboken 8088 was sure to get an earfull about what a grand show the new one would be. There was the memorable time when 22 ==== we closed two shows the same evening. Something like $7000 in cash had to be paid out that day to meet all salaries. It's a lot of money, and it took some brisk shuttling of funds between one box-office and the other to meet all the requirements at the imperative moment. I was tied to my post, for I was trouping that night, but Tom came back during the show, drew me behind a drop, and said with the true Irish in his eye "Well, we may be closing, but anyhow it's with flying colors." After it was all over he repaired to the clam brothel I have already mentioned, had half a dozen of what he needed most, and fell into a peaceful nescience; for which I honor him. Let none take these intimacies amiss; they are of the blood and heartbeat of Show Business; as 23 ==== much a part of its immortal pulse as the proudest gala performance. So can you wonder that we love her? That she takes on in our minds a meaning somewhat beyond what you may actually see in her rather dingy fabric? Over the window of that miniature box office we put up last autumn a tablet in honor of Dion Boucicault, to the effect that his play had "brought an old theatre back to life and restored a fine tradition of the stage." That tradition we tried to carry on in the revival of The Blue and The Gray, a melodrama as American as Boucicault's was British. I hear a good deal said and argued about the Death of the Theatre. There isn't much wrong with the theatre when a forgotten old playhouse can arouse such devotion as she 24 ==== has had from her servants, and can give such Elizabethan hilarities to her audience. She caters Pure Fun—rarest and divinest commodity of all. It can easily be marred by the ignorant, who will never know that Fun also has its sensibilities. But for those who are capable of Fun she offers an experience. Let no man be fool enough to try to explain too fully what or why he loves. My mistress has given me what I never knew I would have; what indeed no man ever foresaw having—several gray hairs. 25 ==== page [26] blank ==== page [27] section or chapter title: A Little Back Room ==== page [28] blank ==== page [29] 2 IN a small and most unfashionable hotel, which in this age of grotesque discretions I suppose I must not identify, there is a little back room in the basement. Its most devoted habitues reach it by a secret rear access through a neighboring garage, not only because by such entry they evade the coat-check damsel in the lobby upstairs, but also because the more obvious road into this re- ==== treat is through a doorway misleadingly superscribed LADIE'S, which startles the delicate-minded. It is true there is still another approach, by a secret winding stair, but this very few know. The little back room, however reached, has grown much endeared to a certain coterie of beachcombers who occasionally sit there either for secret counsel or for loquacious relaxation. There the waiters of the hotel sit for their own hasty meals, snatched at off-hours; resorting thither about the aperitive hour you are likely to find Fritz or Hans hastily leaping up and bearing off with him his hard-earned plate of chowder. And to all conferences held in that modest chamber Mike the barkeep is a party. In time past the hotel had a regular barroom on the street level; but this 30 ==== later era has reduced it to a mere cupboard in the basement. The bar itself is only a shelf across the doorway, but Mike still has the cunningest hand at an Old-Fashioned cocktail that has yet been encountered. It is he, spurred on by his admiring clients in the Little Back Room, who invented the Deep Dish Old-Fashioned, which, without any larger quantity of alcoholic spirit, exceeds in bulk and flavor any cocktail ever known. And Mike, roosting on his elbows on his tiny bar and brooding like some tutelary presence over his customers in the little room opposite, is a psychic reality to be reckoned with. --- The Little Back Room, you are remarking with some reproach, is only a kind of speakeasy. 31 ==== Well there is even a possible suggestion in the word. In that small basement, which large plumbing pipes and valves give so nautical an air (rather like an engineers' mess in the belly of a liner) speech is easy. There have been moments when anxieties and pressures seemed to drop away; when Mike's golden calorific brought excellent meanings to utterance; when a plain tumbler was not just a glass but a chalice. The mettlesome whang of the little dance orchestra in the slippery grillroom nearby faded to a murmurous diapason ; time faltered in its reeling orbit. I can think of occasions when those usually reticent became angels of candor and shot off like Roman candles. Even in the intervals of difficult decision the goddess of comedy has been known to slip in and take 32 ==== the seat which is always reserved for her; men, as is their saving virtue, have punctuated perplexity with screams of mirth. So if a speakeasy is a place where truth is made easier to speak, I approve it. Mike sees plenty of publicans and sinners and asks them no questions. Monday, however, is his night off; his locum tenens does not properly understand the technique of the Deep Dish. --- There is no deep-laid reason for my alluding to the Little Back Room just now, except that at Christmas time, I suppose, one instinctively thinks of all wholenesses of living. It is customary to formalize the season as one of clear cold darkness and gemmed with stars (a Black, Starr and Frost season, Fifth Avenue might remark) but 33 ==== there have been December dusks that were very chill and gray. It is regrettable, one has noticed, that the essential Christmas feeling does not usually penetrate us until the Date itself is so near that we cannot catch up. By the time we find in ourselves the Ten-Day-Before-Christmas sentiment there are only two days left. But there must be some deliberate artistry of the great ironist in the festival of peace being preceded by such billows of pressure; by all the prickliest anxieties and humblest difficulties of the year. It is then that Capital gets cowardly, that the radiator freezes and coal runs low in the bin; that roads are crusted with sleet, fillings come out of teeth, and the mails swell with the thousand appeals of tragic need. At that time, when (in theory) one would 34 ==== relish the generous pleasures of chance, one is most bedevilled by detail. Then if ever one would like to savor to the brim the huge punchbowl of life, to mark the slow curves of loveliness and the acute zigzags of comedy. And it is exactly then that consciousness is most teased to the tingling quick by the push of the immediate affair. Suddenly you grow honest with yourself and know you would not have it otherwise. And you may chance to remind yourself that the holiday we celebrate is in honor of the greatest artist of all, in so far as we can guess at his character. It is rather incredible that we should all pay tribute to him, for we have so little of his recklessness, his noble folly, his consuming mirth. He was never afraid of absurdity. Surely to him can be applied 35 ==== those echoing words Conrad wrote of the artist in general—"He appeals to that part of our being which is not dependent on wisdom; to that in us which is a gift and not an acquisition. He speaks to our capacity for delight and wonder, to the sense of mystery surrounding our lives; to our sense of pity, and beauty, and pain." 36 [end text] === pp [37-38 blank] ==== page [39] Of this edition 225 copies have been printed for THE FOUNDRY PRESS: R. C. RIMINGTON by The Marchbanks Press, New York, of which copies number 1 to 25 are for hilarity, and copies 26 to 225 are for sale. Distributed exclusively by the PHOENIX BOOK SHOP 41 E. 49th Street, New York City THIS IS COPY NO. [handwritten] 2 === Status: OK Status By: dw Status Date: 2012-08-16

![pg [ii]; pg [iii]: half title](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/bae14af0-faf2-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFhKJ1Q.tn.jpg)

![pg [iv]; page [1]: title page (note author's name is autograph only)](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/bc13d780-faf2-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFhKJsJ.tn.jpg)

![pp [2-3] verso title; chapter title: Apologia Pro Sua Preoccupatione](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/bd446840-faf2-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFhKK0S.tn.jpg)

![pg [4-5]: chapter (or section) 1](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/be76a6b0-faf2-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFhKLwt.tn.jpg)

![pp 24-25 [end chapter 1]](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/ca63a130-faf2-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFhKQQO.tn.jpg)

![pp [26-27]: blank; section title: A Little Back Room](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/cb94ce30-faf2-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFhKQmh.tn.jpg)

![pp [28-29]: blank; chapter or section 2](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/ccc6be80-faf2-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFhKRSN.tn.jpg)

![pg 36 end text; pg [37] blank](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/d18b9990-faf2-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFhKTRP.tn.jpg)

![pg [38] blank; pg [39] colophon with limitation, copy no. 2](https://d3f1jyudfg58oi.cloudfront.net/11047/image/d2bc5160-faf2-11ed-a641-b3912f9925a9-uFhKTld.tn.jpg)