Collections Item Detail

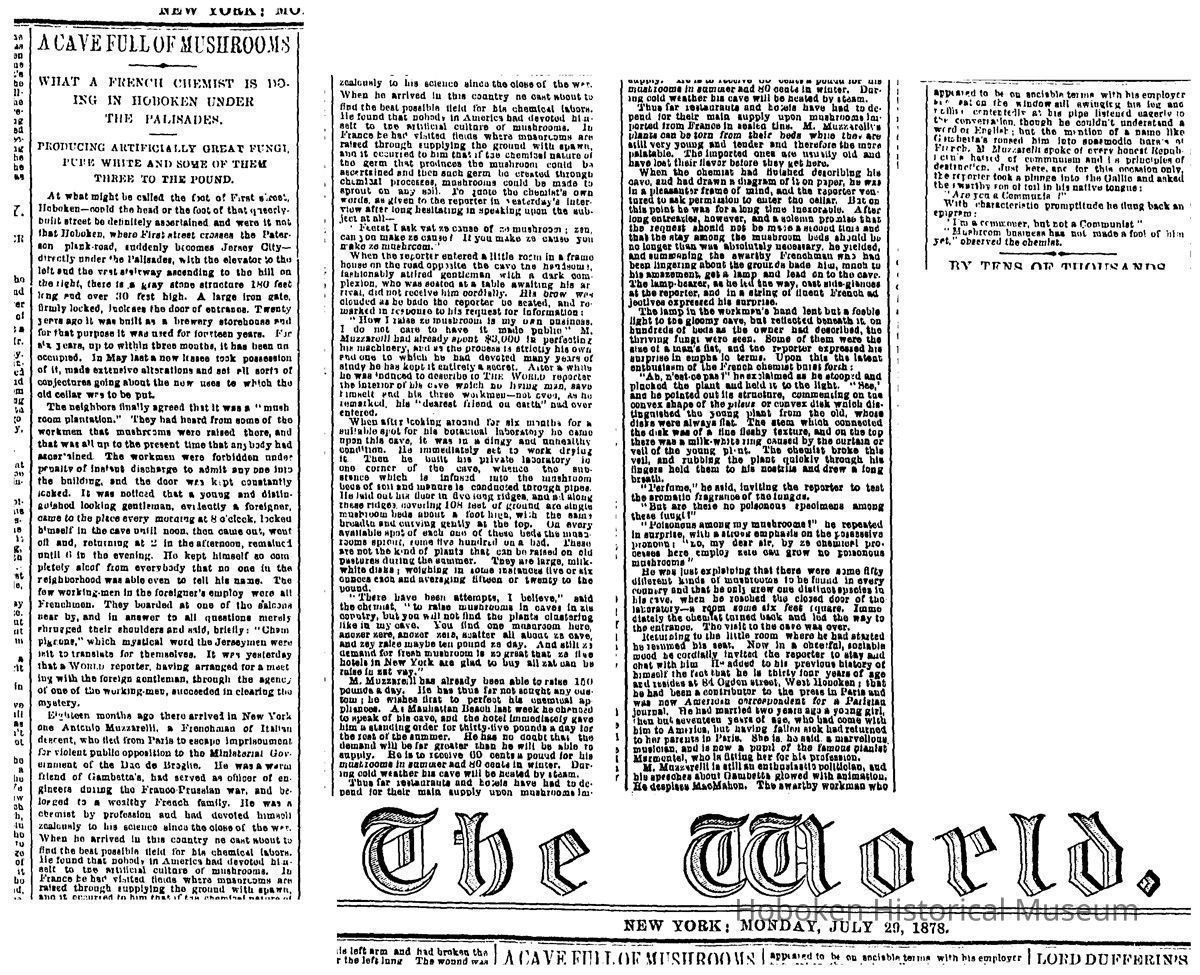

Article re Antonio Muzzarelli: A Cave Full of Mushrooms; What a French Chemist Is Doing in Hoboken Under the Palisades; Producing Artificially Great Fungi... Newspaper: The World, July 29, 1878.

2013.029.0001

2013.029

Kidd, Karen

Gift

Courtesy of Karen Kidd.

1878 - 1878

Date(s) Created: 1878 Date(s): 1878

Notes: Archives 2013.029.0001 Newspaper: The World New York, Monday, July 29, 1878. Volume XIX, No. 6187 Transcription of article column, 3; end at top of column 4 ==== A CAVE FULL OF MUSHROOMS WHAT A FRENCH CHEMIST IS DOING IN HOBOKEN UNDER THE PALISADES. Producing Artificially Great Fungi, Pure White and Some of Them Three to the Pound. At what might be called the foot of First street, Hoboken - could the head or foot of that queerly-built street be definitely ascertained and were it not that Hoboken, where First street crosses the Paterson plank road, suddenly becomes Jersey City - directly under the Palisades, with the elevator to the left and the vast stairway ascending to the hill on the right, there is a gray stone structure 180 feet long and over 30 feet high. A large iron gate firmly locked, blocks the door of entrance. Twenty years ago it was built as a brewery storehouse and for that purpose was used for fourteen years. For six years, up to within three months, it has been unoccupied. In May last a new lessee took possession of it, made extensive alterations and set all sorts of conjectures going about the new uses to which the old cellar was to be put. The neighbors finally agreed that it was a "mushroom plantation." They had heard from some of the workmen that mushrooms were raised there, and that was all up to the present time that anybody had ascertained. The workmen were forbidden under penalty of instant discharge to admit any one into the building and the door was kept constantly locked. It was noticed that a young and distinguished looking gentleman, evidently a foreigner, came to the place every morning at 8 o'clock, locked himself in the cave until noon, then came out, went off and, returning at 2 in the afternoon, remained until 6 in the evening. He kept to himself so completely aloof from everybody that no one in the neighborhood was able to even tell his name. The few working-men in the foreigner's employ were all Frenchmen. They boarded at one of the saloons near by, and in answer to all questions merely shrugged their shoulders and said, briefly" " Champignons," which mystical word the Jerseymen were left to translate for themselves. It was yesterday that a WORLD reporter, having arranged for a meeting with the foreign gentlemen, through the agency of one the working-men, succeeded in clearing the mystery. Eighteen months ago there arrived in New York one Antonio Muzzarelli, a Frenchman of Italian descent, who fled from Paris to escape imprisonment for violent public opposition to the Ministerial Government of the Duc de Broglie. He was a warm friend of Gambetta's, had served as officer of engineers during the Franco-Prussian war, and belonged to a wealthy French family. He was a chemist by profession and had devoted himself zealously to his science since the close of the war. When he arrived in this country he cast about to find the best possible field for his chemical labors. He found that nobody in America had devoted himself to the artificial culture of mushrooms. In France he had visited fields where mushrooms are raised through supplying the ground with spawn, and it occurred to him that if the chemical nature of the germ that produces the mushroom could be ascertained and then such germ be created through chemical processes, mushrooms could be mad to sprout on any soil. To quote the chemist's own words, as given to the reporter in yesterday's interview after long hesitating in speaking upon the subject at all - 'Feerst I ask vat za cause of ze mushroom' zen, can you make ze cause! If you make ze you make ze mushroom. ' When the reporter entered a little room in a frame house on the road opposite the cave the handsome, fashionably attired gentleman with a dark complexion, who was seated at a table awaiting his arrival, did not receive him cordially. His brow was clouded as he bade the reporter be seated, and remarked in response to his request for information: " How I raise ze mushroom is my own business. I do not care to have it made public." M. Muzzarelli had already spent $3,000 in perfecting his machinery, and is the process, is strictly his own and one to which he had devoted many years of study he has kept it entirely a secret. After a while he was induced to describe to THE WORLD reporter the interior of his cave which no living man, save himself and his three workmen - not even, as he remarked, his " dearest friend on earth " had every entered. When after looking around for six months for a suitable spot for his botanical laboratory he came upon this cave, it was in a dingy and unhealthy condition. He immediately set to work drying it. Then he built his private laboratory in one corner of the cave, whence the substance which is infused into the mushroom beds of soil and manure is conducted through pipes. He laid out the floor in five long ridges, and all along these ridge, covering 108 feet of ground are single mushroom beds about a foot high, with the same breadth and curving gently at the top. On every available spot of each one of these beds the mushrooms sprout, some five hundred on a bed. These are not the kind of plants that can be raised on old pastures during the summer. They are large, milk-white disks; weighing in some instances five or six ounces and averaging fifteen or twenty to the pound. "There have been attempts, I believe," said the chemist, "to raise mushrooms in zis country, but you will not find the plants clustering like in my cave. You find one mushroom here, anozer zere, anozer sere, scatter all about ze cave, and zey raise maybe ten pound ze day. And still ze demand for fresh mushrooms is zo great that ze [illegible] hotels in New York are glad to buy all zat can be raise in zat vay." M. Muzzarelli has already been able to raise 150 pounds a day. He had thus far not sought any custom; he wishes first to perfect his chemical appliances. At Manhattan Beach last week he chanced to speak of his cave, and the hotel immediately gave him a standing order for thirty-five pounds a day for the rest of the summer. He has not doubts that the demand will be far greater than he will be able to supply. He is to receive 60 cents a pound for his mushrooms in summer and 80 cents in winter. During cold weather his cave will be heated by steam. Thus far restaurants and hotels have had to depend for their main supply upon mushrooms imported from France in sealed tins. M. Muzzarelli's plants can be torn from their beds while they are still very young and tender and therefore the more palatable. The imported ones are usually old and have lost their flavor before they get here. When the chemist had finished describing his cave, and had drawn a diagram of it on paper, he was in a pleasanter frame of mind, and the reporter ventured to ask permission to enter the cellar. But on this point he was for a long time inexorable. After long entreaties, however, and a solemn promise that the request should not be made a second time and that the stay among the mushroom beds should be no longer than was absolutely necessary, he yielded, and summoning the swarthy Frenchman who had been lingering about the grounds bade him, much to his amazement, get a lamp and lead on to the cave. The lamp-bearer, as he led the way, cast side-glances at the reporter, and in a string of fluent French adjectives expressed his surprise. The lamp in the workman's hand lent but a feeble light to the gloomy cave, but reflected beneath it, on hundreds of beds as the owner had described, the thriving fungi were seen. Some of them were the size of a man's fist, and the reporter expressed his surprise in emphatic terms. Upon this the latent enthusiasm of the French chemist burst forth: "Ah, n'est ce pas!" he exclaimed as he stopped and plucked the plant and held it to the light. "See," and he pointed out the its structure, commenting on the convex shape of the pileus or convex disk which distinguished the young plant from the old, whose disks were always flat. The stem which connected the disk was of a fine fleshy texture, and on the top there was a milk-white ring caused by the curtain or veil of the young plant. The chemist broke this veil, and rubbing the plant quickly through his fingers held them to his nostrils and drew a long breath. "Perfume," he said, inviting the reporter to test the aromatic fragrance of the fungus. "But are there no poisonous specimens among these fungi?" "Poisonous among my mushrooms?' he repeated in surprise, with a strong emphasis on the possessive pronoun; "no, my dear sir, by ze chemical processes here employ zere can grow no poisonous mushrooms." He was just explaining that there were some fifty different kinds of mushrooms to be found in every country and that he only grew on distinct species in his cave, when he reached the closed door of the laboratory - a room some six feet square. Immediately the chemist turned back and let the way to the entrance. The visit to the cave was over. Returning to the little room where he had started he resumed his seat. Now in a cheerful, sociable mood he cordially invited the reporter to say and chat with him. He added to his previous history of himself the fact that he is thirty four years of age and resides at 84 Ogden street, West Hoboken; that he had been a contributor to the press in Paris and was now American correspondent for a Parisian journal. He had married two years ago a young girl, then but seventeen years of age, who had come with him to America, but having fallen sick had returned to her parents in Paris. She is, he said, a marvellous musician, and is now a pupil of the famous pianist Marmontel, who is fitting her for his profession. M. Muzzarelli is still an enthusiastic politician, and his speeches about Gambetta glowed with animation. He deplore MacMahon. The swarthy workman who appeared to be on sociable terms with his employer [illegible] sat on the window sill swinging his leg and puffed(?) contentedly at his pipe listened eagerly to the conversation, though he couldn't understand a work of English; but the mention of a name like Gambetta's roused him into spasmodic [illegible] of French. M. Muzzarelli spoke of every honest Republican's hatred of communism and its principles of destruction. Just here, and for this occasion only, the reporter took a plunge in the Gallic and asked the swarthy son of toil in his native tongue: "Are you a Communist?" With characteristic promptitude he flung back an epigram: "I'm a commoner, but not a Communist." "Mushroom business had not made a fool of him yet, " observed the chemist. [end] ==== ==== Status: OK Status By: dw Status Date: 2013-05-23